Wasting away: Effluent water bolsters urban agriculture, but poses serious health risks

Farmers cope with water pollution in their efforts to feed millions

by Sarah Haughn

Circle of Blue

Cities above and below the equator rely on the fruits of urban agriculture, literally. According to a new report, many farmers use human sewage to irrigate that agriculture. The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) estimates that 800 million people grow and eat food produced in cities. But times are changing: the climate is unpredictable, and water is scarce. While farmers on the outskirts of the world’s metropolises feed many, they now struggle to irrigate their crops. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) predicts that in twenty years at least two-thirds of the world’s population will live in cities, making access to clean water for urban agriculture more crucial than ever.

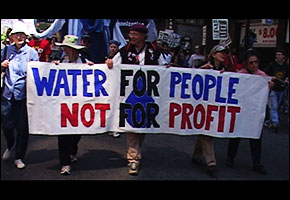

As water supplies dwindle and water itself becomes a commodity, new research asks the question: how can low-income urban farmers ensure safe water for their produce? The report, released for World Water Week in Stockholm, reveals that millions of farmers across the globe currently resort to water saturated with human sewage for irrigation. While irrigation with raw sewage delivers unexpected benefits, it also presents tremendous health risks for farmers, consumers, and the environment.

Conducted by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), the report — Drivers and characteristics of wastewater agriculture in developing countries — covers more than 53 cities across Asia, Africa and Latin America. It explores why so many farmers use wastewater, as well as how the quality of such water impacts the food they grow.

Waste not, want not

As growth in cities outpaces the capacity of urban infrastructure, many mid- to low-income farmers — for whom clean freshwater is either unavailable or too costly — turn to untreated wastewater as a solution, write study authors Liqa Rachid-Sally and Priyantha Jayakody. They note “the close relation between wastewater use and physical water scarcity.” Agriculture comprises over 70 percent of freshwater use worldwide. Of this percentage, at least 200 million farmers irrigate 20 million hectares (approximately 50 million acres) with wastewater.

There are benefits to doing so. Urban wastewater — made of domestic and industrial effluent, and run-off — actually contains nutrients that nourish food crops. The wastewater contains fertilizing nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus, most farmers cannot afford. The application of wastewater is also a simple way to prevent some surface water pollution.

In cities from Africa to Asia, wastewater provides poor families with financial security. It allows them to grow a variety of fresh and nutritious foods, improving their health. They sell the food in urban centers, which provides them with much needed income, as well as a chance to improve their livelihoods. Many of the 26 developing countries studied lack the infrastructure to transport and refrigerate produce. Informal urban farming that takes advantage of free and readily available wastewater for irrigation provides a local, affordable alternative.

But is it safe?

Although it does produce significant benefits, wastewater irrigation undeniably puts the health of many who cannot afford medical care at risk. “While wastewater has the potential to serve as a hitherto untapped water and nutrient source for agriculture; where treatment is limited it also has the potential to affect human health and pollute large volumes of freshwater rendering them unfit for human uses,” the study states.

Substituting highly available and cost-free wastewater for exceedingly scarce and expensive fresh water seems to be a sustainable alternative, but just how safe is wastewater irrigation for those consuming the produce it saturates? IWMI’s latest research determines that the true risks remain unknown.

In low-income countries with developing infrastructure, many farmers use untreated wastewater rich with raw sewage — which poses higher health threats to both growers and consumers. Parasites and pathogens thrive in feces, easily infecting those exposed through irrigation or consumption of unwashed produce. Aside from basic hygiene practices, urban farmers surveyed for the study demonstrated little direct knowledge of how untreated wastewater can impact human health. Consumers surveyed indicated that while they do wash their produce, it is often in the same untreated water.

Untreated wastewater not only directly threatens urban populations. It potentially adds elements to the soil that are harmful to people, elements which food crops then absorb. Such use can contribute negatively to watersheds, facilitating the transport of salt or polluting the surface and groundwater with microbiological contaminants.

The urban farmer’s way forward

Yet, not everyone is unaware. Urban farmers from Burkina Faso to Nepal, Vietnam and Indonesia store untreated wastewater in tanks and ponds, allowing sediment to settle before use. They use their five senses to detect whether the water is pure enough. In Cambodia, farmers dilute dirty water with clean water. Chilean farmers in Santiago choose to grow crops that do not easily absorb specific pollutants.

Leaving such solutions up to the will of their citizens, few developing countries have outlined responses to deal with some of the risks of using wastewater to irrigate crops near and in urban centers. Of the 26 countries surveyed, only 12 say they follow guidelines to regulate wastewater use. Even where such use is forbidden, government offices rarely enforce regulation. In water-scarce Faisalabad, Pakistan use of untreated wastewater is banned, yet authorities auction off the polluted resource for great profits during dry seasons. In Nam Dinh, Vietnam the government pumps wastewater out of the drainage system for irrigation.

While water pollution poses a serious threat, treated wastewater could solve urban farmers’ irrigation dilemma. Tunisia, a country located in drought-fraught North Africa, integrates wastewater treatment into its national water resources management strategy. More than 62 plants treat Tunisia’s wastewater, which is then re-used to irrigate agriculture. While treated water still costs more than conventional water, the government subsidizes it to ensure that farmers can afford it.

For the millions who utilize free untreated wastewater to feed burgeoning cities, outlawing use does not sound like a realistic option. “From a livelihoods perspective therefore it must be remembered that extreme responses to minimizing risks from irrigated agriculture, like banning the use of polluted water, could have important adverse effects not only on farmers but also other sectors of the economy and society and urban food supply unless alternatives are made available,” the report concludes.

IWMI recommends that cities follow guidelines set out by the World Health Organization and FAO, which encourage safe use of wastewater — use that connects policy with improved sanitation. They also recommend separating domestic and industrial discharge. Rather than creating sophisticated agricultural infrastructure, they suggest taking better care of that which is already available.

The researchers conclude that, in the end, “a research gap clearly exists.” No one yet knows quite what the risks are. More research is needed to determine the actual impact untreated wastewater visits upon the millions of people worldwide who consume the produce it affords.

Sarah Haughn is a Circle of Blue staff writer and researcher. Reach her at circleofblue.org/contact.

Download the IMWI report here.

Thank you for your informative and enlightening article.

Too often water scarcity, agriculture and food production literature tends to be linked to rural environments, agro-industry, and inappropriate use of fertilizers, pesticides and inefficient irrigation methods. For me the article was a wake-up call about urban fresh food farming and production.

This was not necessarily due to the information concerning the potential and very real harm being caused to human health by the use of untreated urban wastewater for urban irrigation purposes. Rather it was because it placed food farming and production within the urban environment where so many people, often migrants from former rural food producing areas, are now dependent upon food grown in urban centres. These are the same urban centres where water scarcity, inappropriate over-use, and increasing and competing demands already exist.

I am now led to wonder where urban food production will be placed when competing demands are prioritised?

water pollution is a great threat to world.This can cause great problem to our future generation.All world should take serious step to solve this problem as early as possible.

A great problem ! Let us work together with integrated composion of professinals

to make a difference in waste management(solid & liquid) to secure our environment for tomorrow’s generation!!! Exprince exchange through workshops & training to overcome this worldwide probelm without no compromise! I expect you to establish an international organization that will react to the situation.

Thank you!!!

Alemayehu Neme Eticha

Oromia Water Quality Control Lab,Ethiopia,Africa