Understanding Zimbabwe: An Interview with Professor Timothy Burke

In an interview with Circle of Blue, Swarthmore history professor Timothy Burke discusses the land, race and water politics behind Zimbabwe’s current Cholera crisis. He explains the complex history of colonization and corruption that caused the nation’s recent collapse, and explores possible roles the West may or may not play in solving the problem. A cultural historian, Burke has spent time studying both Zimbabwe and South Africa. The interview was conducted as part of Circle of Blue’s coverage on the Cholera outbreak in Zimbabwe.

Has water played a role in the building of Zimbabwe as a country? Has water ever been a source of conflict or cooperation in Zimbabwe?

Yes, water is important in the history of Zimbabwe, in several respects. First, the country has several significantly different distributions of rainfall: the southeast is low-lying but relatively dry, whereas the highland plateau in the north-central part of the country is relatively well-watered in many parts. However, the entire region is and has been subject to periodic cycles of high rainfall and drought, and this has certainly had an effect on African societies in the region over the last three or four centuries.

After the colonial subjugation of Zimbabwe in 1890, several successive phases of land seizure by white rulers tended to move African farmers to more arid areas of the country, with more marginal soils. So there was a “politics of water” involved in this case as well.

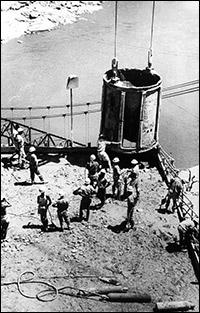

The most specific episode of political conflict over water management, however, was the damming of the Zambezi River and the creation of Lake Kariba by the Rhodesia government, which displaced many Tonga people who had been living in the river valley.

Since independence, there have been a number of local conflicts over water-rights management, but the background to the cholera epidemic is a more humdrum case of poor stewardship of infrastructure (both water supply and health care).

The current cholera catastrophe in Zimbabwe is most commonly linked to the disintegration of the healthcare infrastructure. What are some of the major factors and important nuances to bear in mind when looking at the disintegration of water and sanitation infrastructure during Mugabe’s regime?

One of the common misperceptions of the crisis in Zimbabwe is that it began suddenly with the seizure of white farms in the late 1990s. The roots lie deeper, arguably almost to the beginning of the postcolonial era in the early 1980s. At the very least, by the early 1990s, the government was already beginning a process of “hollowing out” key government departments, using them largely as a dumping ground for patronage jobs while paying little heed to the need to deliver effective services to the public.

There was very little investment made in expanding the capacity of public services or infrastructure where expansion was needed, and funds for maintenance of existing infrastructure were poorly spent or diverted to an increasing degree as the 1990s wore on. In many ways, the controversy over land reform was a calculated attempt to divert international and local attention from the acceleration of internal corruption. This affected water and sanitation as much as any other area of service.

There is a deeper structural issue to keep in mind, however. Colonial governments throughout the region, including the Rhodesian government, also had a consistent aversion to the construction of even minimal water and sanitation infrastructure in the townships in which Africans were allowed to live. The apartheid state in South Africa took this policy to particular extremes, but it was a consistent colonial approach.

Even given the corruption of the postcolonial Zimbabwean state, they inherited a water and sanitation infrastructure that was in many respects deliberately crippled…

Even given the corruption of the postcolonial Zimbabwean state, they inherited a water and sanitation infrastructure that was in many respects deliberately crippled…

The reasoning behind this deliberate failure to build infrastructure was that Africans were supposed to be “temporary” residents in urban areas, and to build even minimal infrastructure of this kind would have been an admission that urban populations were permanent. So even given the corruption of the postcolonial Zimbabwean state, they inherited a water and sanitation infrastructure that was in many respects deliberately crippled and lacking capacity.

Historically speaking, what presence or reputation has the U.N. and the international NGO community in general assumed in Zimbabwe? Has Mugabe’s government taken a different stance on international aid than various populations in the country?

The UN and NGO community are regarded with indifference in most parts of the country, I think. Not hostility: it’s more that people don’t expect very much out of NGOs, but they’re certainly also glad to get whatever they can get from them, and grateful for support. When a particular community has a long-standing relationship with a particular NGO, there tend to be more definite and sustained feelings.

The ZANU-PF dominated government has never taken international institutions particularly seriously as a constraint on their own actions. I think they have wanted to get some measure of respect, especially from the Commonwealth, but never to the extent that they would alter their own course of action in a serious or sustained way.

There have been isolated exceptions to this pattern. Timothy Stamps, the former health minister (until 2002) was often very solicitious of international organizations and cooperated closely with NGOs. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the finance ministry was also fairly solicitious of good relations with international organizations.

What are the risks of intervention on the part of “the West,” especially after Ian Smith? Why has the African Union not been more present in or vocal toward the situation in Zimbabwe?

In one sense, there are no risks to intervention on the part of the West, since the kinds of interventions which would be risky simply aren’t going to happen. Condemnation by G8 leaders aren’t going to change the behavior of the ZANU-PF leadership, but neither would “quiet diplomacy”.

The G8 leadership has virtually no influence over ZANU-PF and virtually no tools for exerting pressure over it. So in those circumstances, strongly voiced moral clarity and consistent condemnation are helpful in that they define and defend important international standards, but no one should expect much more than that from such condemnation. Any stronger scenarios for intervention simply aren’t in the cards and most of them shouldn’t be.

The AU, on the other hand, could have a much bigger impact than it has so far, and most of that comes down to South Africa’s reluctance to bring public pressure to bear on the Zimbabwean government. There are a variety of reasons for that reluctance, most of them indefensible. Part of it has been a reluctance to appear to be doing the bidding of Western governments. Part of it is that the South African government has been reluctant to establish a standard for transgression which might circumscribe its own future freedom of action. Part of it may be an unwillingness to risk ZANU-PF rebuffing a strong public criticism, thereby putting the South African government in the position of having to up the ante in some respect.

Many leaders in the international community are calling for Mugabe’s resignation. Looking back, do you think that this step will benefit or harm Zimbabwe’s current situation? Based on your knowledge of Zimbabwe’s political past and its current ethnic makeup, what immediate impacts might a regime change have on the water and sanitation crisis?

What I think global observers don’t understand about Zimbabwe is that it is presently an undeclared military dictatorship. I don’t mean to minimize Mugabe’s own personal authority and political skills–he continues to exert a surprising degree of personal control, using some of the tactics that he has employed his entire life. But the effective power behind the scenes is a small set of military officers and police commanders. They are the ones who do not want to allow the opposition to take power, or to allow any serious reform to take place.

They also have very little interest in improving governance or services, only in protecting their own wealth and power from scrutiny. They remain confident in their ability to control the course of events through intimidation and violence. If Mugabe were to die tomorrow or to resign, these men would then face a choice of whether to bring another civilian figurehead to the fore or to step up and take power directly. I think they’d prefer not to do the latter. But Mugabe’s resignation, unless it were accompanied by a genuine concession of power by the military and police, will do little in and of itself to reverse the decline.

If such a genuine concession happened, some things could change relatively quickly. There is a large population of educated, skilled Zimbabwean expatriates who might be willing to return home and participate in the reform and reconstruction of government services–though I think some kind of international aid or support for such reconstruction would also make the difference between success and failure.

There are many trials and tribulations across the continent of Africa. Why this story, this crisis? Why now?

To some extent, American and European interest in Zimbabwe was initially catalyzed by the seizure of the white farms, which is probably not the best reason to pay attention. I do think however that the Zimbabwean story is a bit different than many other stories of failure in postcolonial Africa because much of it is so clearly unnecessary.

Some postcolonial states have been crippled by situations not of their own making, but the Zimbabwean government had a lot of tools to work with in the 1980s and early 1990s, which it systematically squandered. So as a story of misrule, this is an especially depressing and frustrating case and perhaps that accounts for some of the interest.

I think it is now a self-sustaining story: people follow it because they’ve heard about what happened last and now they want to know what happens next.

Interview by Sarah Haughn for Circle of Blue, December 09, 2008

How about the sanctions professor? Have they not contributed to the collapse of infrastructure? Washington has made it clear that there will be no development support until land tenure patterns revert to pre-1998 structures. Why is the West so reluctant to admit that their sanctions – both declared and undeclared – have killed the country. Zimbabwe last got a penny from the IMF in 1998. Is it not a coincidence that all this support dried up when the Zimbabwe Government embarked on a land reform programme that has seen over 300 000 FAMILIES occupying land previously held by 4 500 white farmers?

To talk of the post-colonial era after 1980 is perhaps unfortunate. Rhodesia was self-governing from 1923 and, although rejected by the rest of the world, “independent” since 1965. From then until 1980 the country endured the full force of world-wide sanctions but despite this continued to thrive and expand; so that when Mugabe eventually took over the running of the country Health, Education and Agriculture were examples to the rest of Africa.

Prof. Burke does not realise how efficient water supply and sanitation to the townships was; that it continued to function although on a continuing and increasing downward slope due to lack of maintenance until very recently – perhaps the last two or three years. That all major dams, irrigation projects and sewerage disposal plants had been built by the Rhodesian authorities.

Finally, I think Prof. Burke underestimates Mugabe. Thanks to the system of patronage and corruption that he has created he remains firmly in control.