America’s Water Supply: Scarcity Becoming Endemic

Public awareness reflects troubles with access and supply.

By Steve Kellman

Circle of Blue

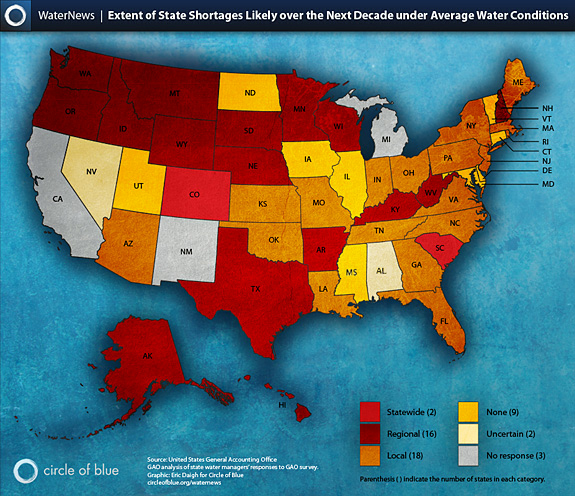

Americans have good reason to be concerned about the future of the nation’s supply of clean fresh water, according to state and federal research and resource agencies.

The U.S. Drought Monitor, a weekly online report produced by the Department of Agriculture and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, notes in its latest assessment that one-third of the continental United States is suffering abnormally dry or drought conditions.

Drought conditions grip more than half of the West, with little change from the same time last year. The hardest-hit areas include California, in its third year of a statewide drought, and Arizona, which has been experiencing abnormally dry or drought conditions since August .

Groundwater resources, which provide half of the country’s drinking water as well as irrigation for crops and water for industrial use, also are diminishing, according to the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) Groundwater Resources Program. The Ogallala Aquifer, the massive groundwater network that lies under the Great Plains and feeds water to more than a quarter of the region’s irrigated land, continues to be a significant concern.

“Basically the groundwater is being depleted of its resource,” said Kevin Dennehy, the USGS project coordinator. “It’s been happening for quite some time and it’s going to continue to happen. The removal of water from the aquifer is at a greater rate than water is being re-charged in the aquifer naturally.”

Federal and state authorities aren’t the only ones concerned about America’s vulnerability. In August, Circle of Blue released the results of a public opinion survey in the United States that found Americans are worried about water, particularly water pollution (with 57 percent very concerned), the lack of safe drinking water (56 percent very concerned) and the lack of water for agriculture (47 percent very concerned).

And while those surveyed said they feel somewhat empowered to address water problems, they also feel more information is needed to protect the resource. The survey results in the United States were consistent with the findings of Circle of Blue’s global public opinion poll, which asked 20,000 people in 15 countries how they felt about their water supplies. The overwhelming response: people around the world see the declining quality and increasing scarcity of fresh water as a considerable threat to public health, national economies, and the quality of life.

Indeed, as Circle of Blue reported last year, increased competition for water in the United States poses a growing threat to the American way of life. Scientists and resource specialists warned that freshwater scarcity was hurting farm productivity, limiting some regional economic growth, increasing business expenses and draining local treasuries.

The deteriorating condition of the Ogallala is a case in point. According to a June USGS report water from the aquifer is generally acceptable for drinking, irrigation, and livestock. But irrigation and leakage of nutrients down inactive irrigation wells is increasing concentrations of contaminants including nitrates deep in the aquifer, posing long-term risks to its safety as a source of drinking water.

Wild Weather Predicted

Even regions of the country that are rich in water resources are not secure. The Great Lakes, for instance, and the entire Midwest are under potential threat from climate change. A series of recent reports by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) on climate change in the Midwest warns that higher temperatures will take a toll on the Great Lakes water levels over the course of this century, with evaporation increasing in the summers and ice formation slowing in the winters.

In a worst-case scenario, water levels for all five Great Lakes could fall by an average of one to two feet, with Lake Huron and Lake Michigan facing the sharpest declines. Such declines will affect beach and coastal ecosystems, expose toxic contaminants and hinder recreational boating and commercial shipping. This could be particularly troubling for Michigan, a state with more than a million recreational boaters and more shoreline than any other state but Alaska.

Melanie Fitzpatrick, a climate scientist with UCS’ Climate Program, said in an interview with Circle of Blue that her organization’s findings were based on two scenarios—one that predicts lower emission levels in coming decades and another that estimates higher emission levels.

“They depend on our population, they depend on our emissions choices and they depend on the kind of technology we might create,” she said.

The lower emission scenario is based on global adoption of emission limits like those in the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009 (ACES), which the U.S. House passed in June. ACES calls for reducing the nation’s carbon emission levels between 17 and 20 percent by 2020.

The higher emission scenario was meant to reflect a worst-case scenario, Dr. Fitzpatrick said. “Unfortunately, our emissions are currently tracking higher than that high-emission scenario,” she added.

Under either scenario, increasing temperatures could shift rainfall patterns across the Midwest—resulting in less rain in the summer, but more in the winter, spring and fall.

With heavy rains already twice as frequent as they were a century ago, the Midwest should brace for even heavier downpours in the coming decades and more frequent floods like those that inundated the region in 2008.

“We know that that’s already a problem,” Dr. Fitzpatrick said, “Spring flooding is a problem in agriculture in terms of farmers getting into their fields to sow their crops, and we’ve seen some really significant flooding.”

She cited the Red River in western Minnesota and eastern North Dakota as an example. In the spring of 1997, the river rose to record levels, killing 11 people, causing billions of dollars in damage, and forcing more than 60,000 people from their homes. While that flood was thought to be a once-in-a-hundred-years event at the time, similar floods followed in 2001, 2006 and 2009, with the river reaching its highest level in recorded history this spring in Fargo, North Dakota.

In Wisconsin last year, much of the state experienced its wettest June. Six inches of rain fell on the town of Ontario in a single day, and flash floods swept away homes, roads and bridges. In the popular resort town of Wisconsin Dells, water overtopped a highway separating Lake Delton from the Wisconsin River, creating a washout that drained the lake dry.

Increased flooding is dangerous for water quality as well as life and property.

“These flash floods and heavy rainfall events are already a problem in cities like Philadelphia that don’t have adequate combined sewer overflow capacity,” Dr. Fitzpatrick noted. In Philadelphia and other cities where sewage systems are combined with storm water drainage systems, heavy rains can overflow the systems, and divert the wastewater into nearby streams and rivers.

Paradoxically, the Midwest also faces the possibility of more frequent short-term droughts in the coming decades due to falling amounts of summer rainfall combined with rising temperatures. Long-term droughts should be less frequent, according to the UCS report.

Solutions

Such grim scenarios are prompting state and federal scientists and engineers to develop new safeguards for water. In California, a new three-dimensional water-modeling tool developed by USGS scientists provides a detailed picture of the water flow in the Central Valley Aqufier, which lies beneath the 400-mile stretch of land.

The tool can help planners cope with increasing demands on the aquifer, which is home to one-sixth of the nation’s irrigated fields and 6.5 million residents in California’s fastest growing region.

“This tool is helping the local planners and water managers better assess current and future conditions with regard to their water resources,” Dennehy said.

Growing Demands on the Great Lakes

Three years ago the eight Great Lakes states agreed to a regional water compact that was ratified by Congress in September 2008 to provide new protections for withdrawing water. The Great Lakes Compact prevents bulk diversions of Great Lakes water out of the region and sets new standards for conservation and environmental protection for the region.

While the compact was hailed as a landmark water protection measure, critics are concerned that a loophole in the language still leaves the lakes exposed to the possibility of large-scale for-profit exports of Great Lakes water in the form of bottled water.

U.S. Rep. Bart Stupak, a Democrat of Michigan, introduced a Congressional resolution in June to close the loophole by expressly prohibiting Great Lakes water from being sold, diverted or exported outside the region. The bill has since been referred to a House subcommittee.

For more on U.S. water issues, check out CoB’s series on inter-state water conflicts, featuring South Carolina v. North Carolina, Nevada v. Utah, Mississippi v. Tennessee, Georgia v. Tennessee, and Alabama v. Florida v. Georgia.

|

Water Tops Climate Change as Global Priority: a comprehensive public opinion survey on attitudes about fresh water sustainability, management and conservation finds that people around the world view water issues as the planet’s top environmental problem. |

Steve Kellman is a Circle of Blue writer and reporter. Reach him at circleofblue.org/contact.

It definitely seems like we have more and more people finding more and more uses for the same water supply. Eventually, you get to the point where you are trying to take more than Mother Nature is putting in.