A Rice Town’s Cry

Will the sky ever listen again?

by Keith Schneider

Photographs by J. Carl Ganter

Circle of Blue Reports

DENILIQUIN, New South Wales – Late in the afternoon on December 16, 2008, as Phillipa (Pip) Rinaldi cleaned the glassware and readied her family’s bar and restaurant for the evening’s guests, she heard the first heavy drops of rain on the roof of the Riverview Motel.

After more than a decade of severe drought, which more than three years ago forced Pip, her younger sister, and her parents to give up a farming life outside Deniliquin for a much harder existence as motel and restaurant owners in town, the midsummer shower seemed almost punitive, a damp excuse.

“It has been so hard, this drought,” said Pip, 22, who has a degree in occupational therapy, and after hoping to start her professional life in “Deni,” was just weeks away from starting her career in Perth, 2,700 miles west. “Moving into town and being completely separated from the farm, you lose your space. You have a feeling of isolation in town. Even though we’ve got the motel and quite a lot of room, it’s still small compared to where we were before. It’s a very different lifestyle. Not being on a farm has changed who I am a bit.”

Shrinking Prospects

The same can be said for this New South Wales town of 7,500 residents, most of whom are in one way or another tied to agriculture. Just eight years ago, Deniliquin was the center of a rice-growing region that produced a record 1.7-million-ton, $700-million crop. Much of that was processed, milled and exported by Sun Rice, a growers’ cooperative that represented more than half of Australia’s 2,500 rice farmers and is the fourth largest rice producer in the world. Sun Rice owned and operated the 39-year-old Deniliquin mill, the largest rice processor in the southern hemisphere. Before the drought, during rice harvests that typically started in March and lasted for months, trucks backed up from the gates of the mill, not far from Deniliquin’s center square, in a line that stretched for blocks and blocks, waiting to unload the crop.

However, since the late 1990s, the epic drought in the Murray Darling Basin steadily diminished – and then last year wiped out – Australia’s rice crop. Just like the American Midwest, where factory closures ripped town economies, Deniliquin’s vanished rice economy is steadily disabling the culture of security, expectation, and familiarity that it once fostered. Perhaps most importantly, Deniliquin is now losing, arguably, its most important resource, today’s brightest young minds – just like those that have sustained it since the town’s settlement in the 19th century. And something less tangible: The characteristic Australian good cheer has been replaced by a grim stoicism.

“There’s not a lot happening, and that is the thing,” Pip said. “There’s not a lot happening at all, compared to what it used to be. The rice harvest used to be a big part of this town – it was enormous. It used to go for months on end. Basically 24/7. There were trucks on the road. Everyone was busy. The whole town was basically abuzz with rice harvest. Now you wouldn’t even notice when the rice harvest is on.”

One Family’s Move

Pip’s father, Frank Rinaldi, bought his 700-acre farm about half an hour outside Deniliquin specifically to raise rice. Good crops meant prosperity for his family and the community. He sent his daughters to boarding school in Melbourne. Some nights during the harvest, the line of trucks was so long that Pip was dispatched by her mother, Dianne, to pick Frank up and bring him home for a few hours’ sleep, returning him to the line at 5 o’clock in the morning. The town ebbed and flowed with the rice harvest.

“It was exciting,” said Pip. “There was so much happening. All the farmers were happy. They all had good crops. Those were full and busy hours. Harvest is your busiest time of year. That’s when your greatest profits come in. And when you get to the end of rice harvest, you have a cut out, and everyone gets to party and enjoy themselves. It’s a big thing in this town.”

But as the drought gained a tighter grip on the Murray-Darling Basin, emptying the reservoirs and forcing New South Wales authorities to reduce water allocations to rice growers starting in 2000, the crop diminished. In 2003, producers raised 400,000 tons. In 2007, 200,000 tons. Last year, production amounted to just 18,000 tons, about the same as what the industry’s leaders anticipate this year, and the lowest harvest since 1929.

The Rinaldi family, more fortunate than most, sold their farm in 2004. A neighbor made an offer, and then the Riverview Motel came on the market. The family, having endured two straight years without a rice crop that painted their bank statements with red ink, made the move.

Layoffs at the Mill, Emptying Streets, Lives Ruined

It came just in time. On November 8, 2007, Sun Rice chairman Gerry Lawson posted a notice in the region’s newspapers and sent letters to co-op members that said the company was “temporarily downscaling,” a euphemism for its decision to shut the 39-year-old Deniliquin mill and a second in Coleambally. Workers were sent home four days before Christmas. A shift at the mill in Leeton also was shut down. Roughly 225 people lost their jobs.

The long lines of trucks haven’t been seen in Deniliquin since. But in their place came empty storefronts and dozens and dozens of “For Sale” signs in neighborhoods once so stable that when people moved in or out it was almost a community event.

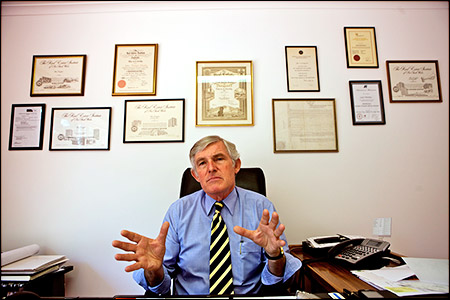

“Our market here for residential houses is probably the worse it has been in the 35 years that I’ve been here,” said Lester Wheatly, a Deniliquin real estate broker. “In the last 12 months, our buyer inquiry rate has dropped by about 80 percent. That’s pretty powerful stuff.”

A number of the Rinaldis’ friends, hopeful that the drought would end, got stuck with land and equipment they couldn’t use and declining prospects for off-farm jobs. Marriages broke up. There was so much stress that in 2005, when mental health authorities held a meeting to talk about the situation, more than 2,000 people showed up.

Still, the suicide rate in the Deniliquin region is twice the national average, according to federal health authorities. Serious farm accidents are on the rise, the result of tired growers trying to do too much on their own to save money.

Human Toll

The toll on service workers also is high. Di Rinaldi, Pip’s mother, is a trained nurse who rose to become administrator of the 61-bed Deniliquin Hospital. She ended her health career to help with the motel, but still serves as the volunteer board chair of the Deniliquin Community Center. She sees dimensions of the drought and the farm crisis that few people do. She describes a bank manager, a friend, who had worked for 35 years in the business and recently quit. He told her he couldn’t face one more foreclosure, one more wrecked family.

One night, not long ago, Di said, Frank came home very upset. “He said, ‘I need you to go with me to the pub tomorrow night. There’s this guy down there. Things aren’t going well for him. His wife has just walked out. His farm is going badly. And I think he’s suicidal.’” She told her husband to intervene on his own, which he did, apparently successfully.

“The men never had to think about suicide. They think it’s a weakness thing, you know?” she said. “They actually all have had to look at it now, though, because there have been so many in the area. Even among the youth in this area, it’s huge. Young males. It’s really scary, and the drought is the cause.”

On that December night as Pip was preparing to open the restaurant, the rain fell for a time, producing puddles in the street outside the Riverview Motel, and quieting the birds. Then, just as it has done for a decade, it stopped. “My parents sold the farm on my 18th birthday,” said Pip. “I was at my boarding school at the time. I came home to celebrate my birthday, and my parents pulled me aside and said we sold the farm. I was distraught. I’d been on the farm my whole life. It was who I was. I was a country girl. I loved bringing my city friends home, just showing them how I lived.”

She recalled this without tears, in a matter-of-fact way. She had moved on, past the hurt and the fear. Still, it can rise up in her again at any time. “To see something go from fantastic to how it is now, where it is nothing, is really horrible,” she said.

Keith Schneider, a former New York Times national correspondent, is senior editor and producer at Circle of Blue. J. Carl Ganter, an award-winning photojournalist, writer and broadcast reporter, is the co-founder and director of Circle of Blue. Contact Keith Schneider or contact Ganter at carl.ganter@circleofblue.org. For a complete list of credits, acknowledgements and other resources related to Circle of Blue’s coverage of “The Biggest Dry” please click here.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!