Coal Ash: Town’s Toxic Water Embodies National Challenge

Dirty Legacy Contaminates Groundwater of an Indiana Town

Uncovered coal ash roads like this one are a common sight in the Town of Pines. The ash once used as filler material for roads, building projects and dumped in the local landfill, now contaminates the ground water in the small town.

Uncovered coal ash roads like this one are a common sight in the Town of Pines. The ash once used as filler material for roads, building projects and dumped in the local landfill, now contaminates the ground water in the small town.Text, Video, and Images by Aaron Jaffe

Map by Yiruo Zhao

Circle of Blue

TOWN OF PINES, Ind. — Peggy Richardson was still in high school nearly 40 years ago when trucks began dumping the ash from a nearby coal-fired power plant in this working-class community 50 miles east of Chicago.

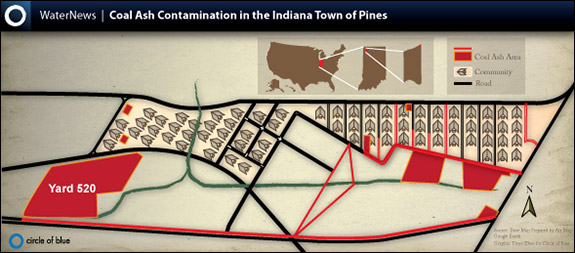

Like the other 800 residents, she and her family never considered whether there was a risk when a heap of ash –- known here as Yard 520 — steadily grew into a mountain of coal wastes a half-mile long and four stories tall, higher than any building in town.

Even today the risks of coal ash in the Town of Pines are not perfectly clear. In addition to Yard 520, ash was spread across the town, dumped as the foundation for roads and as fill for construction sites. Nine years ago, a resident alerted the federal Environmental Protection Agency that there was something wrong with their drinking water. The EPA found heavy metals and other contaminants in groundwater in the region.

Richardson, who lives just blocks from the ash mountain, has a good idea that exposure to contaminated water and such close proximity to Yard 520 is not safe. What leads her to this conclusion? During an interview in her kitchen here she reached into a drawer and pulled out a stainless steel table knife she bought less than a year ago. The metal blade was scarred and pitted. “This water eats my sink and silverware,” she said. “What has it done to me?”

In the next week — after nearly a decade of deliberation — the EPA is scheduled to release a report that will add more clarity to the consequences of coal ash in the Town of Pines, and define a formal path to cleaning up a landfill that contains over one million tons of coal wastes.

“Currently, we’re working on the remedial investigation,” said Tim Drexler, the EPA’s Yard 520 project manager. “The disposal predated a lot of regulations both on a state and a federal level.”

The federal environmental agency got involved in 2000 after a resident reported that her water smelled like a “beauty salon.” Today, Yard 520 is slated for cleanup as an Alternative Superfund Site — an EPA program that takes care of abandoned toxic waste sites.

Though it is one of the largest coal ash piles in the Great Lakes basin, Yard 520 nevertheless is just one example of the trail of some 600 impoundments, landfills, and storage ponds for coal wastes that are scattered across the Midwest and other regions of the United States, according to the EPA. Some 63 are toxic and leaking. Most have grown to huge dimensions, in part because neither the federal nor state governments required the same stringent health and environmental safeguards that apply to municipal landfills or chemical toxic waste sites.

That may change. In December a coal ash storage pond in Tennessee ruptured, spilling more than a billion gallons of ash slurry laden with heavy metals — a spill 50 times larger than the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster — into tributaries of the Tennessee River. In a new report published earlier this month that was prompted by the Tennessee incident, the EPA detailed 44 “high hazard potential” coal ash storage pond dump sites across the country.

Yard 520 is not one of those high hazard sites. But its rigorously documented history of seeps and water contamination make it an emblem of the multiple costs of generating power from coal and a factor in the growing national debate over clean energy, climate change and the American economy.

There are more than 500 power plants across the United States that burn coal, producing more than 100 million tons of coal ash annually — enough to fill a million railroad cars. Some ash finds its way into industry products, but more than half of it is dumped into landfills like Yard 520 or into holding ponds like those in Tennessee.

Regardless of the storage method, environmental scientists say, when water and coal ash mix they generate hazardous compounds that are readily mobile. In the Town of Pines, toxins from the coal ash mixed with the shallow water table to release a plume of contamination into the town’s groundwater. The legacy of this town’s ash pile is the long-running struggle here to secure clean fresh water.

Peggy Richardson’s drinking water, for instance, comes from five-gallon jugs. Though the majority of the town has municipal water, Richardson is still waiting for a line to reach her house. “I felt sorry for the people who started doing this, but at some point they had to have known it wasn’t good,” she said, “which is when I stop feeling sorry.”

All of the Community

In the early 1970s, the Northern Indiana Public Service Corporation began dumping ash from its nearby coal-fired power plant in a cattail-filled wetland in the Town of Pines. Mixing with the groundwater, the ash generated a plume of contaminants that seeped from the landfill, according to the EPA. Toxic levels of heavy metals, including lead, arsenic, manganese and boron seeped into the town’s wells.

For the past nine years, EPA conducted tests, while residents sued. Though city water is provided to some residents, the struggle to secure safe water for the whole town has been an uphill battle. In 2002 seven residents formed People in Need of Environmental Safety, or PINES. The advocacy group is credited with many of the successes in contending with the coal ash.

A founding member of the group, 72-year-old Jan Nona has been a resident for 43 years and is at the center of the PINES strategy and execution. Nona has convened neighbors, gone to EPA hearings, and met with senators and representatives in her kitchen to combat the coal ash contamination. Nona’s “war room” is a study stacked with binders and boxes full of documents, videotapes, photographs and contact sheets. Living in an elderly community with a background in industry, she makes it clear that she is not a “tree hugger.”

“I’m an activist as far as the community is concerned,” Nona said, “not an environmentalist.”

“We’ve still got groundwater contamination which they’re probably never going to be able to eliminate,” she said. “We’ve still got a million ton of fly ash landfill that they’re never going to be able to get rid of. We’ve still got fly ash all over town in road, driveways and yards that we’re probably never going to get rid of. This town is trashed.”

Nona added: “You have the right to safe drinking water in this country. They took that right away from us.”

Another lifelong resident is Debbie Loyd, 49, who watched her community being built on a foundation of black fly ash. Local contractors dumped the ash everywhere, a building block for the village infrastructure — filling in lots, making roadbeds, driveways and even serving as the base of a playground.

“It’s not just the landfill — it’s all of the community,” Loyd said.

She remembers biking a paper route through the town as a child just when the ash was packed down for roadbeds. The black dust would swirl in clouds along the ditches during the summer, turning into a pitch, gooey “quicksand” when it rained.

In the beginning town leaders saw the ash as benign. “For many years, fly ash was viewed by many to be a wonderful fill that could be used for a variety of things like road-bedding, like filling in low areas, and this town took advantage of that,” said Paul Kysel, vice president of PINES. As the trucks hauling coal ash came, residents assumed officials were on the lookout for any hazards and that the monitoring wells that dot the perimeter of the landfill would alert them if anything was wrong.

They were wrong. Groundwater tests dating back to the 1980s show that high arsenic levels seeped from the landfill. Residents say they were never told about the contaminants.

Many residents, among them Gordon Tharp, feel betrayed. Forging a living in the steel mills and making bridges, Gordon and his wife, Pat, moved into their house in the heart of the Town of Pines 36 years ago, a week before their second daughter was born.

Like the rest of the community, the Tharps thought the ash was harmless. “What did I do to my grandchildren and what did I do to my children,” Gordon Tharp asked. He cannot see an effect, but “what could have been” is always at the back of his mind.

“They knew that those wells were bad, but they never told anybody. They kept it a secret,” Tharp said.

Living with the Legacy

In the wake of the discovery of contamination, Debbie Loyd stopped remodeling her house because property values plunged. She has a new bathroom that has never been connected to running water.

Loyd remembers what the water from her well used to be like. “It got to the point where it was sucking fly ash straight, and the check valve in my well wouldn’t close. My sinks wouldn’t shut off because I had all of that fly ash in there. I had to replace everything.”

Despite declining property values and environmental damage, Nona sees the drinking water contamination as something more fundamental.

After residents filed a federal lawsuit, the companies responsible for the groundwater contamination agreed in 2004 to pay to extend municipal water from nearby Michigan City to about two-thirds of Pines. For the PINES group and the community, this was a major victory, but Cathi Murray still remembers what was coming out of her tap for years on end.

Murray moved to Pines from Chicago with her husband Allen nearly 20 years ago. Drawn by the natural beauty of the area, the Murrays were looking for a house to settle down and raise a family.

It was not until after the birth of her two daughters — one is hearing impaired and another was born with a rare bowel disorder — that she learned about the water. “I will always wonder that in trying to do the best for my babies, did I actually poison them?” Murray asked.

For Peggy Richardson, the victory was bittersweet. She lives closer to Yard 520 than many others but is still without municipal water. Living off of five-gallon containers, the water that ate away two faucets and a stainless steel sink still gurgles up from her well. “I worry I’m going to live the rest of my time out with contaminated water,” she said.

“There’s no way to get away from it — you can’t sell your house, your property value just goes in the toilet,” Richardson said. “It’s a waiting game.”

Aaron Jaffe is a video producer and reporter for Circle of Blue. Reach him at circleofblue.org/contact.

As someone who use to live near The Pines and attended Pine Twp Elem starting in 1958, 1st grade to 6th grade 1963, my heart goes out to each of you. I can no longer remember my 1st grade teachers name, but I remember, all my other teacher’s name’s and most of the children I attended school with. Mrs. Deal, Mrs. Lowe, Mrs. Miller. Mr. Sells and Mr. Dunn. My school bus driver was Mr. Rittenmyer. I attened Chesterton during my 7th and 8th grades then Barker Jr. High for part of my 9th grade. I live in Tennessee, I’m a retired nurse who has spent years putting pieces to a health puzzle together. You’re not alone, recently we had a coal ash disaster in east Tn, come to find out there was no liner, and about 8 miles west of where I live in Middle Tn, there’s another coal ash plant and there’s no liner in it, either. It’s a disaster waiting to happen. The research I’ve done is that our county has the highest cancer rates or did than any other county in the entire state of Tn. My heart goes out to all you. Soft hugs & prayers.

Other reasons to quit burning coal:

Peggy, I went to school with a Norma Richardson who lived in The Pines, Indiana, is she a relative? A few days ago the NCF added more information to their website re: water contamination by radiation. All any of us can do is hope it’s not too late to undo the damages. Run your mouse over my name and then click on it, the NCF website may help you find answers to some of the health issues plagueing folks there in Indiana. I lived on County Lind Road which is not far from The Pines. Haven’t been back in several years, but still keep in touch with some I went to school with all those years ago. Very sorry and sad to hear of the health issues and depreciation of land and home value’s. Losing one’s health is bad enough but not being able to sell at a fair market value that’s now not even listed at a fair market value, is pretty unfair.

Soft hugs & prayers, Diana

Follow up and an update: EPA agrees to look into town’s radiation problem: http://www.sfgate.com/news/science/article/EPA-agrees-to-look-into-town-s-radiation-concerns-4170911.php

Soft hugs and prayers to all,

Diana