Interstellar H20: Discovering the Origins of Water in the Universe

The European Space Agency’s Herschel Space Observatory Will Search for the Answers to Star Formation, Water Creation and More

Atop the Ariane 5 rocket in Kourou, French Guiana, Herschel waits for its May launch. Named after the British astronomer William Herschel, who discover the infrared spectrum and Uranus, the observatory is the largest space telescope ever launched. Photo courtesy of the ESA (click image to enlarge).

Atop the Ariane 5 rocket in Kourou, French Guiana, Herschel waits for its May launch. Named after the British astronomer William Herschel, who discover the infrared spectrum and Uranus, the observatory is the largest space telescope ever launched. Photo courtesy of the ESA (click image to enlarge). by Nadya Ivanova

Infographic by Hannah Nester

Circle of Blue

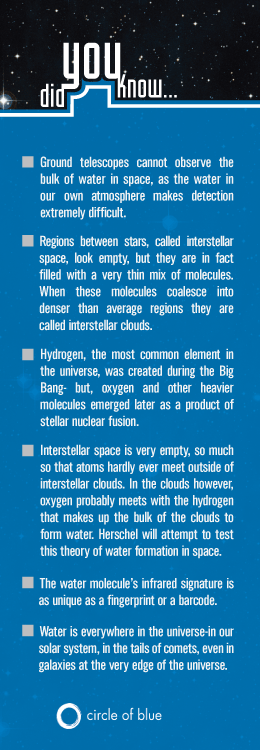

When in 1969 Joni Mitchell, in her song “Woodstock,” wrote “We are stardust…,” she expressed –- as any astronomer will tell you -– a scientific fact as well as a glaring rock metaphor. Almost all elements in the universe are literally debris blown off by dying stars — material that is later recycled in the formation of new stars, planets and eventually life.

While water plays a crucial role in these cosmic births, much about its own origin in the universe remains unknown. Today, however, hopes are high, as the largest telescope ever flown into space blasts off into the great unknown to unlock the great secrets of water in the universe. The Herschel Space Observatory, which launched in May, opened its eyes in June to peer deep into the cosmos — into galaxies, star-forming regions and dying stars.

The observatory -– the first of a generation of space giants designed by the European Space Agency (ESA) –- will make a great leap forward for science, as it penetrates into the cold and dusty regions of the universe to study the formation and evolution of galaxies and stars that are invisible to the naked eye and most optical telescopes.

Carrying the largest space telescope, Herschel is also the first observatory to detect a range of wavelengths from the far-infrared to sub-millimeter parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, which are impossible to pick up by human eyes. With its 3.5-meter-diameter mirror –- four times bigger than any previous infrared space telescope -– it will collect almost 20 times as much radiation as its predecessors and unveil a totally different-looking universe.

Herschel, which was named after astronomer William Herschel, who discovered the infrared radiation, is also the sharpest “eye” to have ever searched for water in our galaxy.

“Personally, I am most excited about water, because it’s unique for Herschel,” said Ewine van Dishoeck, an astrochemist at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands and the Max-Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Germany. She will use Herschel to explore the cosmic backyard of the Milky Way, hoping to find answers to the origin and role of water from space. “That is where Herschel is going to give us great breakthroughs,” Dishoeck added.

While water is abundant on Earth and in the Universe, much of what we know about it comes down to mere conjecture. Water on our planet was most likely delivered by impacting bodies such as comets and asteroids –- both of which are rich in water ice and dust -– as they bombarded the planet soon after its formation, at the time of the early Solar System.

“To me, it is very fascinating that molecules that you see today on Earth were likely already formed 4.5 billion years ago,” Dishoeck said.

As it starts to study the chemical composition of comets and asteroids, Herschel will shed new light on the origin of water and the way it was transported to the Earth. Both comets and asteroids formed in the interstellar clouds – the regions of very tenuous gas between stars where other stars and planets are born. Herschel will poke an eye into the clouds to investigate how water molecules formed and how they found their way into our own primitive Solar System.

The telescope will track the location and abundance of water through the distinctive signature of the water molecule, which can be detected best in the infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

The telescope will also compare the signature of space water to that of Earth water — which comes in multiple forms. Pure “heavy water,” or deuterium oxide, accounts for every 1 in 41 million molecules of water here on Earth. The water contains two heavier molecules of hydrogen, which each bear a neutron at their core. Molecular hydrogen generally contains no neutrons, but this heavy “deuterium” isotope accounts for 1 in every 6,500 molecules of hydrogen on Earth.

As scientists compare the amount of heavy water on our planet with that of heavy water in cosmic objects, they are likely to find out whether water on Earth came from the colder Outer Solar System -– where comets abound –- or in the warmer inner part, where asteroids are more abundant.

Moreover, unlike its ESA predecessor — the Infrared Space Observatory -– Herschel is sensitive enough not only to detect water in space, but also to determine its location and abundance. According to Dishoeck, exploring the ubiquity and forms of water in our Galaxy will be essential to the search for life in space, since water –- a presumably indispensable ingredient for life -– exists primarily as a liquid on Earth.

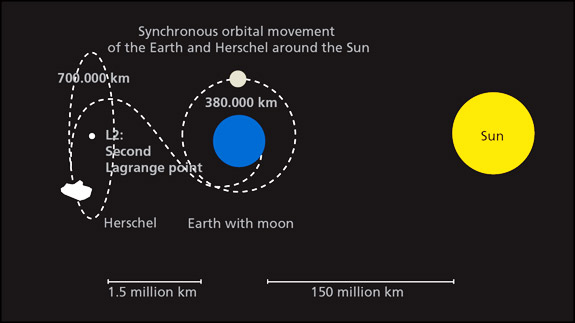

As Herschel travels for a few more weeks to its orbit some 1.5 million kilometers away from the Earth, astronomers anticipate to receive their first signals of invaluable scientific water data as early as the end of November.

Meanwhile, there is also a grain of anxiety and urgency, as the observatory –- the result of more than 20 years of scientific and engineering work and about 1.1 billion Euros of investment -– will be the only mission of its kind for decades ahead, Dishoeck said. The telescope is expected to benefit astronomy for about three years, until it spends the helium that maintains the temperature of its instruments.

“That’s why the Herschel data will be so unique,” Dishoeck said. “It will basically be our only chance for quite a long time to observe water.”

Infographic by Hannah Nester. C.T. Pope contributed to this story. Images published with permission from the European Space Agency (ESA).

, a Bulgaria native, is a Chicago-based reporter for Circle of Blue. She co-writes The Stream, a daily digest of international water news trends.

Interests: Europe, China, Environmental Policy, International Security.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!