Drought, Climate Change Jeopardize Global Hydropower Policies

Climate change is expected to bring less precipitation and more extreme droughts to certain parts of the world, causing electricity shortages in hydro-reliant countries.

On Tuesday Venezuela’s Energy Minister, Ali Rodriguez, said the government would consider purchasing electricity from Colombia, contradicting a statement from the country’s Vice President Elias Jaua given earlier this week. One day before Rodriguez’s announcement, Jaua said he’d reject the Colombian proposal because Venezuela would “power up its own electricity system,” according to Business Week.

On Tuesday Venezuela’s Energy Minister, Ali Rodriguez, said the government would consider purchasing electricity from Colombia, contradicting a statement from the country’s Vice President Elias Jaua given earlier this week. One day before Rodriguez’s announcement, Jaua said he’d reject the Colombian proposal because Venezuela would “power up its own electricity system,” according to Business Week.

These conflicting statements reflect the already confused and poorly managed policies officials have attempted to implement against the country’s worst drought in nearly a century.

In January, electricity rationing in Caracas was suspended after one day because of the chaos created by the power cuts to traffic signals and protests. As a result, energy consumption decreased by only two percent compared to last year–-far short of the goal of a 20 percent reduction, Bloomberg reports.

The source of 70 percent of Venezuela’s electricity is the Guri dam. Low reservoir levels have forced power generation to be curtailed. At its current rate, the water level will drop to critical lows by the summer, in which case all power generation would stop.

Critics argue that if the government had invested more money in the energy sector, Venezuela would have other sources available during the crisis.

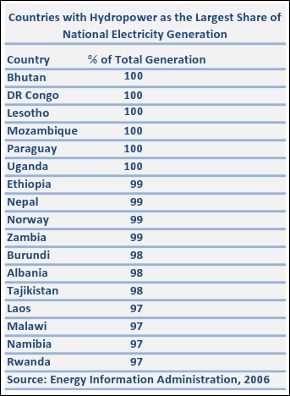

The country’s energy struggles mirror problems in the rest of the hydro-reliant world. Many countries, especially in Africa, use hydroelectric dams to produce nearly all their electricity.

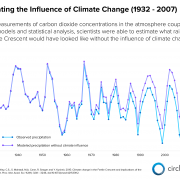

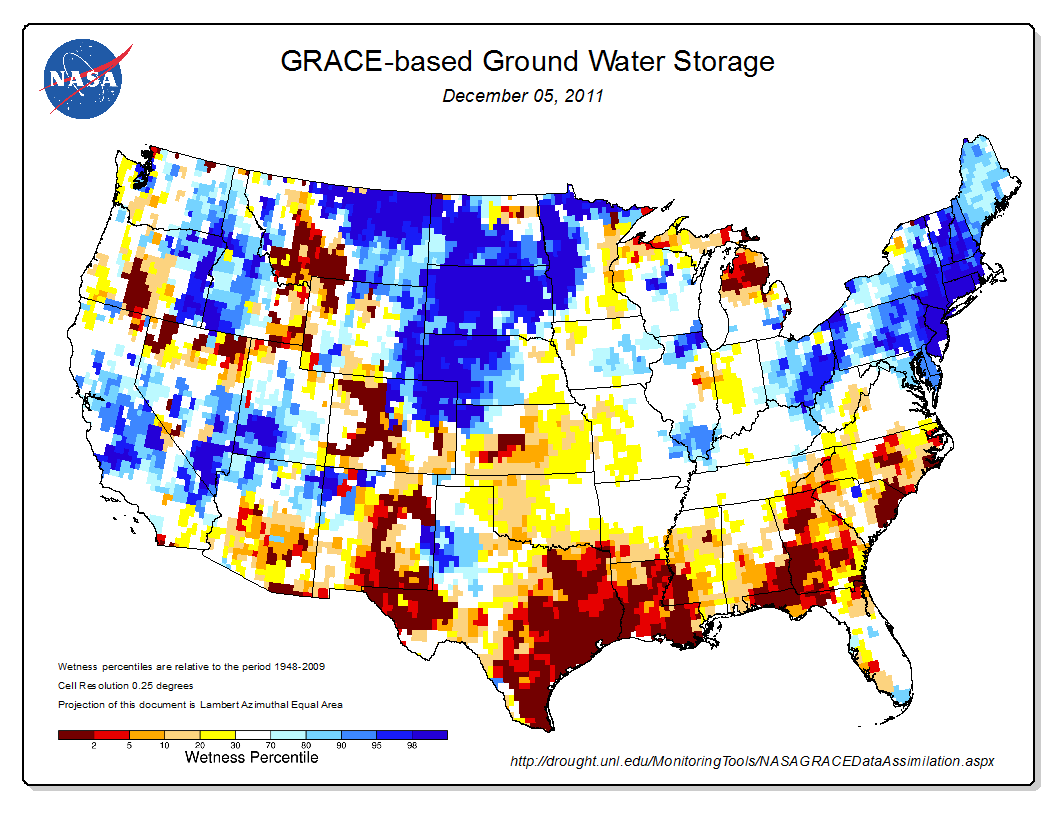

The threat of more extreme drought from climate change is an uncertain variable for many hydroelectric producers. Climate models predict an overall decrease in precipitation and river runoff for the mid-latitude, sub-tropic and dry-tropic areas-–where hydropower is currently the primary source of electricity.

Persistent low water levels in rivers and reservoir cause power cuts, which hinder economic growth and reduce revenue from electricity sales, limiting the ability of an electric utility to maintain the dam.

Some countries have recognized the risk and are already moving toward a more diversified energy future.

After a 2009 drought that led to two months of power rationing, Kenyan Prime Minister Raila Odinga said “the country can no longer continue to rely on hydro-electric power supply,” Business Week reported. Nearly 70 percent of its electricity comes from hydropower.

Kenya is seeking up to $1 billion from international bond markets to finance geothermal and wind energy projects, Business Week reports.

Source: Business Week, Bloomberg

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!