Great Lakes Threats Go Beyond Asian Carp, Invasive Expert Says

Dr. Reuben Keller calls for long-term solutions to protect the Great Lakes, and the Mississippi and Illinois rivers from future aquatic invasive species.

By Steve Kellman

Circle of Blue

Community ecologist Reuben Keller has made a career out of studying aquatic invasive species in freshwater systems like the Great Lakes, and measuring their ecological and economic costs. Now a lecturer with the University of Chicago’s Environmental Studies program, Dr. Keller outlined the threat posed by invaders like Asian carp in a presentation to attendees of an Alliance for the Great Lakes webcast Wednesday.

“This is a really unique situation for invasions into the Great Lakes,” Keller said. “It’s unique in that we can see this invasion coming, and we may have the opportunity to prevent its arrival…. Asian carp gives us this opportunity to be proactive.”

But just like the more than 180 biological invaders that came before it, he warned, “we need to assume that if [Asian carp] make it to the Great Lakes, we’ll never get rid of them.”

The subject of state lawsuits, EPA and Congressional hearings, and U.S. Supreme Court motions, the plankton-gobbling Asian carp threaten the Great Lakes’ $7 billion sportfish industry with their habit of eating the bottom out of the food chain and starving fish farther up the chain. That has led several Great Lakes states to file lawsuits seeking more aggressive carp-blocking efforts. Meanwhile, U.S. legislators are debating bills that would sever the connection between the lakes and the rivers, and a White House-appointed “carp czar” is overseeing the federal control efforts.

Overall, invasive species like Asian carp, zebra mussels, fire ants and purple loosestrife cost the U.S. economy an estimated $120 billion a year, Keller said. He added that aquatic invasive species, in particular, are the largest cause of biodiversity loss in lakes around the world.

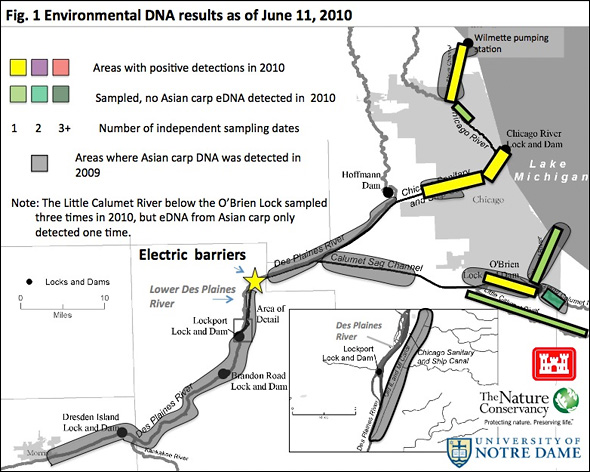

Nearly a year after environmental DNA was discovered upstream of the electrical barriers that are supposed to keep the Asian carp out of the Great Lakes, new tests continue to find evidence that the invasive species has gotten beyond the barriers, according to Keller.

“There’s been a lot of controversy about how we should interpret these results, and I’ll give you my interpretation,” he said. “Asian carp DNA is turning up so often that it is really hard to explain how that DNA is getting there without there being populations of Asian carp that are beyond the electric barrier.”

This suggests that the barriers may not be working as intended to block the fish, Keller said, but even if they do, they still won’t block invasive invertebrate or plant species from getting into the lakes from the rivers, or the other way around.

That has already happened with zebra mussels, which were first discovered in the Great Lakes in 1988 and have since entered into the Mississippi by way of the Chicago-area waterways. Zebra mussels have now spread as far west as California and cause hundreds of millions of dollars in damage in the U.S. every year by fouling the pipes that deliver fresh water to municipal drinking water facilities and power plants.

“We should expect that for many species, the Chicago Area Waterway System is still a very viable conduit,” Keller said. “There’s still a very high likelihood of future invasions, future economic and ecological impacts.”

This is one of the reasons why the Alliance for the Great Lakes supports the permanent hydrological separation of the Great Lakes from the Mississippi River Basin, said Joel Brammeier, the organization’s president.

“Asian carp are only the latest and certainly the most graphic example,” Brammeier said. “But as Dr. Keller mentioned, we’ve already donated zebra mussels and round goby to the Mississippi River Basin, something that I don’t think the other half of the continental United States is too happy about. We can certainly count today half a dozen other invaders in either direction that could move through this system.”

He added, “No technology solution has been demonstrated to be able to provide the kind of certainty against invasion that we think the Great Lakes deserve.”

Brammeier noted that the past year has seen several promising developments in the fight to block Asian carp. In June, the Great Lakes Commission, and the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative kicked off a $2 million study of hydrological separation that is expected to take 18 months to complete. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which oversees the Chicago-area shipping locks that other states are suing to close, is also considering separation as a long-term option.

A bill introduced in Congress in June — the Permanent Prevention of Asian Carp Act — would require the Secretary of the Army to study the feasibility of hydrological separation. Brammeier said the Alliance for the Great Lakes would continue to push for its passage.

With the midterm elections bringing many new faces to Congress and new governors to Great Lakes states like Michigan and Ohio, the Alliance will also need to work on educating the incoming politicians on issues like invasive species, he said.

Steve Kellman is a Circle of Blue writer and reporter. Reach him at circleofblue.org/contact.

I don’t believe that hydrological separation will be any more effective in stopping invasive species than passive barriers. If Zebra Mussels can find their way over the Rocky Mountains all the way to California, how is building a dam or throwing dirt into a canal going to solve the problem. One would think that the Rocky Mountains would be the ultimate hydrological separation, and yet not even the Rocky Mountains have proven to be effective. Also, we cannot overlook the fact that more Asian Carp have been found in Illinois lakes and ponds already hydrologicly separated from waterways containing Asian Carp than have been found above the electric barriers – again proving that hydeological separation simply will not work in stopping Asian Carp.

It would seem foolish to sever strategic commercial and recreational waterways in this country while our global cempetitors in countries such as China are investing billions of dollars to expand their commercial waterways as part of their strategy to dominate world markets by creating transportation infrustructures that move goods at the lowest possible cost.

The Asian Carp and and future invasive species are a 21st century problem. Severing waterways is a 19th century solution that we already know won’t solve the problem. That way of thinking, and going down that path, will only lead to economic disaster while preventing us from pursuing more viable solutions.

We should be smarter than that and get our minds out of the 19th cantury by developing 21st century technology to stop invasive species.