A Desperate Clinch: Coal Production Confronts Water Scarcity

In contest with coal, water takes a beating

By Sierra Crane-Murdoch

Special to Circle of Blue

From its headwaters in Tazewell, the Clinch winds south through the coalfields, feeding mines, preparation facilities, and power plants. It drains the region’s most polluted tributaries before meeting the Tennessee, Ohio, and Mississippi.

One tributary, Dumps Creek, joins the river near this quiet mountain valley town. Most days, the creek runs opaque and brown; some days it runs orange. In 2003, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality drew attention to the acidity, sedimentation, and high concentration of heavy metals in Dumps Creek, but didn’t name the source. Trace the creek to its headwaters, and the source is evident.

Within Dumps Creek’s 20,000-acre watershed there are two active and two abandoned deep mines. There’s also a scraped off mountaintop, fully one-fifth of the watershed, where miners blasted away the topsoil and bedrock to get at the coal. Dumps Creek is critical to these operations—hundreds of thousands of gallons of water are used daily to cool and lubricate mining machinery, wash haul roads and truck wheels to reign in airborne particulates and to suppress underground dust that otherwise could ignite.

The Start of Coal’s Troubled Path

These production practices are only the first stages of an economically essential and ecologically damaging accord between coal and water. Water is critical to every stage of the mining, processing, shipping, and burning of coal. In the era of climate change, swift population growth, and increasing energy demand, the result is a fierce and complex competition between the two resources that has become much more difficult to resolve.

Thirty years ago, high levels of pollution from coal mining and combustion prompted state action and two 1970s national statutes. The Clean Water Act and the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act were designed to limit damage to fresh water resources. Though they made a difference, both laws have never been enforced strictly enough to keep the coal industry from polluting.

More recently, the country’s relationship with coal has come under close scrutiny again because of its environmental costs. Coal companies, seeking greater production efficiencies, use mining techniques that level mountaintops and bury the streams below them. Coal combustion, meanwhile, produces the nation’s largest share of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases that are accelerating global climate change and diminishing the nation’s freshwater reserves.

The Energy Information Administration, a research unit of the federal Department of Energy, forecasts that by 2050 the demand for energy in the U.S. will be 40 percent higher than it is today. As the nation considers what it will take to cool the planet and serve the country’s steadily increasing energy appetite, federal scientists and policy makers are taking a fresh look at how long the coal era will persist, and by necessity the tumultuous space where water and coal intersect.

Little about what they see is reassuring. Scientists define water use by two basic measurements. One is how much water is “withdrawn” from America’s rivers, lakes, and aquifers for domestic, farm, business, and industrial use, most of which is returned to those same sources. The second is how much water is actually “consumed” in products, by livestock, plants and people, or evaporates in industrial processes. In both measurements of withdrawal and consumption coal is at the top of the charts.

The U.S. withdraws 410 billion gallons of water a day from its rivers, lakes and freshwater aquifers. About half is used to cool thermoelectric power plants, and most of that cools coal-powered plants, according to the most recent assessment by the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

Similarly, the U.S. consumes about 100 billion gallons of water a day; nearly 85 percent is used for crop and livestock production. Of the 16.1 billion gallons that remain: industrial, mining and power plants use nearly 8 billion gallons a day, most of that for mining, processing and burning coal, according to the Department of Energy.

Federal and state regulators, and even coal industry executives themselves understand the ropes of ecology, economy and efficiency that are tightening around the nation’s energy sector. Climate change is leading to decreased supplies of rain, snowmelt and fresh water. Energy demand is increasing even as pressure steadily grows to limit greenhouse emissions and reduce water consumption.

To keep coal in the energy mix, industry representatives have readied a fix for climate change—an unproven technology to snare carbon emissions at coal-fired plants and store them deep underground—called “carbon capture and sequestration” or CCS.

But there’s a big problem there, too. Scientists with Sandia National Laboratories who’ve studied carbon capture and storage say CCS will increase water withdrawal and use by 25 percent to 40 percent. In other words, without significant advances in a technology that is only now being tested in a handful of applications, the path to a low-carbon economy that still burns coal will put enormous new pressure on America’s declining supply of fresh water.

“The generation of electricity is inextricably tied to water availability,” said Jeff C. Wright, Director of the Office of Energy Projects at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, during a federal conference on energy and water in April.

“Carbon capture may reduce greenhouse gases going to the air. But it will increase the amount of water needed in thermoelectric plants, coal plants especially.”

A Very Troubled Marriage

Evidence of the unholy water and coal alliance are visible along Dumps Creek. Downstream, amidst towering stockpiles of coal, the Moss 3 Prep Plant pumps hundreds of gallons of water to process each ton that is mined. Like most prep plants, Moss 3 separates the marketable coal from the minerals that will not burn by tossing in a chemical cocktail—the “trade secret,” companies call it—a mix of coagulants and flocculants. Parts of the cocktail are benign, other parts are liable to cause cancer and neurological disorders.

Once the coal is washed, Moss 3 pumps the water-saturated waste—the slurry—back up the mountain into a precariously dammed pond.

Meanwhile, the scrubbed coal, with a lacquer like obsidian, fills trucks and trains that are mostly headed east to coastal cities. But some go three miles to the confluence of Dumps Creek and the Clinch, where Virginia’s top polluting generator, the Clinch River Power Plant, sucks up tens of millions of gallons of water from the river each day. The coal turns the water to steam, the steam powers the turbines, and what’s left of the coal, the fly ash, is scraped from the smokestacks and stored in ponds above the Clinch River.

For as long as the mines have carved out the mountains above the Clinch River, coal has been the region’s heaviest user—and polluter—of water. The same could be said for nearly all of the nation’s coalfields.

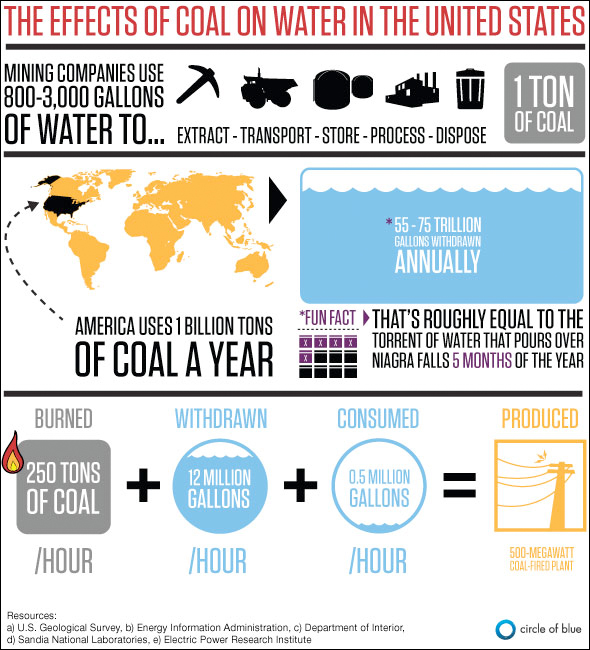

Mining companies use from 800 to 3,000 gallons of water to extract, process, transport and store one short ton of coal and dispose of mining waste, according to estimates by researchers at Virginia Tech University.

The typical 500-megawatt coal-fired utility burns 250 tons of coal per hour, uses 12 million gallons of water an hour—300 million gallons a day—for cooling, according to researchers at Sandia National Laboratories.

To produce and burn the 1 billion tons of coal America uses each year, the mining and utility industries withdraw 55 trillion to 75 trillion gallons of water annually, according to the USGS. That’s roughly equal to the torrent of water that pours over Niagara Falls in five months.

Contamination, Lives and Communities

The amount of water infected with acid mine drainage, chemical spills, and other coal waste is more difficult to calculate. The EPA estimates that since 1992, 2,000 miles of headwater streams have been buried by mountaintop removal, and up to 10,000 miles have been impaired by acid mine drainage. Across Appalachia and other coalfield regions, toxic spills have become a matter of course in the last fifty years. Sludge ponds, when constructed above abandoned deep mines, frequently release coal slurry into shafts and leak into groundwater and streams. Isolated sludge spills have drawn the most public attention, such as the Buffalo Creek disaster in 1972, which killed 125, and a larger flood three decades later in Martin County, Kentucky.

On the Clinch River alone, three toxic spills have punctuated the last half-century. In 1967, 130 million gallons of ash slurry from the Clinch River Power Plant spilled into Dumps Creek; three years later, a cooling tower malfunctioned, gushing sulfuric acid into the river. And in 2008, 5.4 million cubic yards of wet coal ash spilled from Tennessee’s Kingston Fossil Plant into the Clinch. The spill was the largest of its kind in U.S. history.

In 1970, 10 miles downstream from the power plant that bears the river’s name, Tim Bailey stood on a bridge over the Clinch River and watched trout, shiners, darters and bass float south, with their silver bellies bobbing to the surface. He was 10 at the time—old enough to remember the first toxic spill three years before when 200,000 fish died along the 90-mile stretch into Tennessee.

Bailey, now 50, has small, bright eyes and a gray braid down the length of his back. On both shoulders he displays ornate tattoos, spelling the names of his five grandchildren. He and his wife own a tidy doublewide across the street from the Moss 3 Prep Plant, and clustered among several white clapboard houses where his parents and cousins live.

When Bailey was young, he didn’t pay much attention to the changes in the land and water—along Dumps Creek, coal pollution was a fact of life. He swam in the silted streams and hunted in the woods above the power plant. He played tackle football on the slate dump and sediment ponds. But as he got older, he began to notice things.

“When I was first growing up, you could go fishing in these creeks and catch all kinds of fish,” says Bailey. “Now you won’t catch no fish. They’re all killed out.”

On days when coal dust seems especially thick, or when the creek runs orange, he calls the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. The woman he speaks with usually says the same thing: Moss 3 and the power plant are polluting no more than the regulations allow.

It is not unusual for state regulatory agencies to turn a blind eye when coal companies violate the Clean Water Act. In 2009, a New York Times investigation found that state agencies nationwide have taken action against fewer than three percent of Clean Water Act violators. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency also has been reluctant to punish polluters or states that fail to enforce the law. Mining companies and utilities are among the many who have escaped fines and legal consequences.

In recent months, the Obama administration has taken steps to leverage the Clean Water Act to regulate mountaintop removal. In April 2009, the EPA put a hold on five surface mining permits in Appalachia, concerned, they said, with the effects of mining on downstream aquatic life. A year later, the EPA made a public commitment to regulate mine waste and water quality on mountaintop removal sites. In EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson’s words, the new regulations could “zero-out valley fills.”

In June, the Army Corps of Engineers suspended the use of easy-to-obtain NWP 21 permits, which served as rubber stamp gate passes or mining companies to discharge mine wastes into streams and rivers.

Just how committed, though, the White House and its environmental advisors are to stricter enforcement is in question. On June 30, just two months after announcing it would regulate mountaintop mining more strictly, the agency approved the 760-acre Pine Creek Surface Mine in Logan County, West Virginia. According to the mining plan submitted by its owner, Arch Coal, the mine will fill three valleys with debris and bury up to two miles of streams.

Coal’s grip on the Appalachian region remains tight, even as production wanes in Southwest Virginia. Towns along the Clinch River have nearly emptied. Local economies have faltered. In some counties over a quarter of the land has been stripped and mined. On one of these stripped sites sits the steely skeleton of a new 585-megawatt coal plant. Long red arms of cranes bend robotically, hoisting sheet metal to encase the frame. When Dominion Power fires up the plant in 2012, it will draw millions of gallons of water daily from the Clinch.

Still, fish jump and turtles drop from deadwood snags into the Clinch’s murky water. A family of herons and a bald eagle inhabit the trees along the bank. Where the Clinch runs shallow, the white shells of freshwater mussels cling to the bottom, clamped tight against the current.

Sierra Crane-Murdoch, a writer and photographer in Virginia’s coalfields, is a Middlebury Fellow in Environmental Journalism. Graphic by Kalin Wood, a Circle of Blue graphic designer. With contribution from Aubrey Ann Parker, a Circle of Blue reporter and data analyst. Reach them at circleofblue.org/contact.

Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

Heartbreakingly Stupid . Permaculture teaches us our home aand garden can provide most of our water, energy, food and fibre needs. Who needs coal? Plant fruit and nut trees for a future NOW

Great post! Thank you for sharing these information. It is really useful for me.