Energy Department Blocks Disclosure of Road Map to Relieve Critical U.S. Energy-Water Choke Points

Withheld report was requested and funded by Congress.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

A far-reaching federal program of research and analysis, funded by Congress and designed to help the nation anticipate and temper the mounting conflict between rising energy demand and diminishing supplies of fresh water, has been brought to a standstill by the Department of Energy, according to government researchers involved in the project.

The research program, known as the National Energy-Water Roadmap and ordered up by Congress as part of the 2005 Energy Security Act, was meant to provide lawmakers and the executive branch two studies of the impending collision between energy and water, and what to do about it.

The first, completed by a team of federal scientists in December 2006 and made public a month later, described the serious consequences the nation is already encountering as the United States encourages more energy production, the second largest user of water, but gives scant consideration to water supplies, which are in retreat in most regions of the country.

Meanwhile the second and final report that Congress commissioned, a comprehensive research agenda to better understand the nation’s energy-water choke points and begin developing real world solutions, has been held out of public view for more than four years.

22 Rewrites

Michael Hightower, an energy systems analyst at Sandia National Laboratories and a co-author of the report, said the first draft of the study on research needs was delivered to the Energy Department in July 2006. Energy Department reviewers have since called for 22 rewrites, the last of which was delivered in May 2009, Hightower said.

Since then the five-member team that co-authored the study has not had any communication about the report with the two primary reviewers, Samuel F. Baldwin, chief technology officer in the DOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, and Nicholas B. Woodward in the DOE Office of Science.

“I don’t know why they are holding up the report,” said Hightower in an interview with Circle of Blue. “I can only conclude we don’t know how to write or they don’t like the report. I think we have done a nice job in collecting the data. Maybe the quality is in question.”

Neither Baldwin nor Woodward responded to email messages from Circle of Blue. Ebony Meeks, an assistant press secretary, offered this explanation by email and did not respond to follow-up questions: “When developing a comprehensive technological road map it is imperative that all the data is thoroughly reviewed for accuracy and concurred upon by the multiple participating programs. We plan to release the road map as soon as possible.”

A National Water-Energy Conference Without Key Research

The report’s release couldn’t come soon enough for the agency, and the nation. Over the last five weeks, in its Choke Point: U.S. series, Circle of Blue has thoroughly explored the ever more fierce contest between the nation’s insatiable demand for energy, and the tightening supplies of fresh water.

Among the primary conclusions reached in Choke Point: U.S. is that the nation has not yet recognized the significance of the collision between energy demand and water supply to the economy or the environment. The Road Map report was intended to be a vital step toward closing that information gap.

The Energy Department’s decision to prevent the report’s public release could also prove embarrassing. September 26 is the start of the four-day Water/Energy Sustainability Symposium in Pittsburgh, the second annual national conference co-hosted by the Energy Department to “highlight proven and innovative solutions to complex water/energy challenges.” The Pittsburgh conference is the second in a row that could occur without the principal national study that outlines the research priorities. Last year’s conference took place in Salt Lake City.

It is not at all clear why the Energy Department has apparently iced the Road Map. Calls last week to the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, which played an important role in securing funding for the Road Map, received no response.

But a number of clues are contained in a March 2007 Sandia National Laboratories paper that summarized the Road Map’s contents. The paper, prepared by Hightower and three colleagues—Ron Pate, Chris Cameron, and Wayne Einfeld—makes clear that any number of executives in the coal, nuclear, oil, solar thermal, and biofuels industries, and their allies in Congress, could be unhappy about the report’s conclusions. The Sandia paper essentially asserts that the United States quickly needs to reconsider and realign much of its energy production policy and water management practices in order to avoid dire shortages of water and potential shortfalls in energy. None of the big energy production or large water use sectors will be left untouched, the paper indicates.

Few Energy and Water Use Sectors Untouched

“The U.S. energy infrastructure depends heavily on the availability of water, and there is cause for concern about the availability of that water as we look toward future demands on limited water resources,” the authors wrote. “As future demands for energy and water continue to increase, competition for water between the energy, domestic, agricultural, and industrial sectors could significantly impact the reliability and security of future energy production and electric power generation,” they added: “It may not be possible in many areas of the country to meet the country’s growing energy and water needs by following the current U.S. path of largely managing water and energy separately while making small improvements in freshwater supply and small changes in energy and water-use efficiency.”

For instance, the authors raised concerns about U.S. energy policy that is encouraging construction of more coal-fired and nuclear power plants, which use millions of gallons of water an hour, without consideration for where they would be built. The thermo-electric generating sector currently accounts for half of the 400 billion gallons of water withdrawn daily from the nation’s rivers and lakes, principally to cool the plants. The same power plants consume more than 3 billion gallons of water a day, principally through evaporation.

The Energy Information Administration, a unit of the Department of Energy, forecast a nearly 50 percent increase in the demand for electricity between 2005 and 2030. A portion will be filled with energy from the wind and solar photovoltaics, which use virtually no water. Most of the rest will come from new thermoelectric plants.

The Sandia authors noted that new technologies are needed to enable the plants to use coolants other than fresh water, including wastewater from municipal treatment systems, seawater, produced water from mining and drilling operations, and agricultural runoff. In addition, the authors said, U.S. policy encouraging the development of pollution control systems that capture climate-changing emissions and store it deep underground–so-called carbon capture and sequestration–increases water consumption at plants 40 percent to 90 percent.

Advanced Energy Initiative Did Not Consider Water Use

The paper recommends integrating into Congressional and federal policymaking for energy production new requirements for taking into account whether enough water is available for new thermoelectric plants. “The large growth in certain regions of the country of electric power demand and alternative transportation fuel feedstock and refining demands,” the Sandia authors wrote, “suggests that water availability regionally or locally may not be able to support the high growth rate in energy development expected without significant improvements in both energy and fresh water use efficiency.”

The Sandia authors raise similar concerns about rising demand for water to satisfy the nation’s appetite for transportation fuels. In January 2006, President George W. Bush introduced the Advanced Energy Initiative to reduce oil imports and increase national security. One facet of the initiative is to replace 30 percent of the nation’s current gasoline needs with domestically grown and refined biofuels by 2030. This will require production of about 60 billion gallons of ethanol per year by 2030, with over two-thirds needing to come from cellulosic-based feedstocks like switchgrass and wood wastes.

Another facet of the initiative is to encourage production of biodiesel and transportation fuels from tar sands and oil shales in the arid West.

Very clearly, the Sandia authors indicate, the Bush administration did not consider where the water would come from to produce these alternative fuels. “Virtually every alternative transportation fuel being considered will require more water than current petroleum refining,” said the Sandia paper. “A major national scale-up of production capacity and use of nonconventional alternative transportation fuels to meet future domestic fuel demands could significantly increase water demands and impacts.”

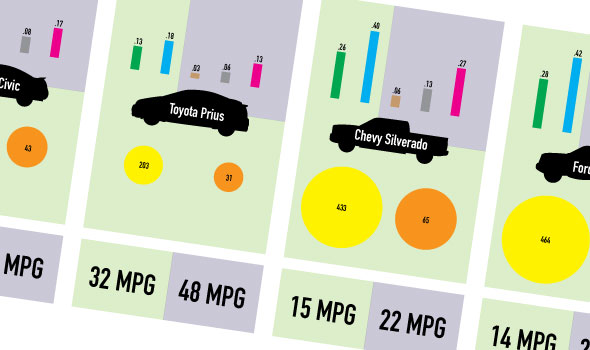

Producing a gallon of gasoline, said the authors, takes about 1.5 gallons of water. Every one of the alternatives promoted in the Advanced Energy Initiative takes more water, from two to six times as much water as petroleum production and refining needs to produce a gallon of fuel. Producing ethanol from irrigated corn fields takes 1,000 gallons of water to produce a gallon of fuel. Producing biodiesel from irrigated soybean fields takes 6,500 gallons to produce a gallon of fuel.

Very clearly, the national alternative fuels plan that relies heavily on producing ethanol raises significant issues about water supply. “Among the issues with the future expansion of biofuel production will be to assure that the availability, use, and sustainability of water and land resources is appropriately managed,” the Sandia paper counseled, “to avoid adverse impacts while not putting undue constraints on the transition toward more biomass-based energy and products industries.”

Planning Needed

Of all the research and policy recommendations summarized in the Sandia paper, and repeated in the Road Map report, perhaps the most significant is the call for linking energy policy and production with water supply and use. The Sandia paper concluded, “As these two resources see increasing demand and growing limitations on supply, energy and water must be recognized as highly interdependent critical resources that need to be managed together in a more integrated way to provide reliable energy and water supplies and sustain future national growth and economic development while maintaining the health of ecosystems and the environment.”

“We need to come up with strategies so we have a sustainable future,” said Hightower. “As it is now in the United States, water is managed by the water group and energy is managed by energy companies. We’ve got to look at the energy infrastructure and the water infrastructure together.

“That’s what we’ve identified as a need in the Road Map report. Hopefully we’ve done something good for the country. Although we’re in trouble with the DOE.”

Keith Schneider is the senior editor of Circle of Blue. Contact Keith Schneider

Read more about energy-water connections in Circle of Blue’s Choke Point: U.S. series.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!