Heart of Dryness: How the Last Bushmen Can Help Us Endure the Coming Age of Permanent Drought

In the sixth installment of Heart of Dryness, author James G. Workman explores the traditional wisdom that has kept the Bushmen alive despite incredibly water-scarce conditions and how the national government threatened their existence. And as recent news indicates, the indigenous peoples continue to struggle for their land rights as Botswana’s government allows safari lodges to be built on the Central Kalahari Game Reserve.

By James G. Workman

Special to Circle of Blue

Within weeks of the court ruling, forty evicted Bushmen sneaked back into the Kalahari, ignoring President Mogae’s attempts to make them stay out. By April 2006, two hundred had returned. Despite dual pressures mounting against them—an increasingly hot sun and vehemently hostile officials—they reinhabited the core of a waterless Reserve at the center of a landlocked country within an increasingly arid subcontinent. For every Bushman caught, accused, arrested and roughed up, several others sneaked in to gather or hunt, prefering to live freely without official help, without water that had strings attached.

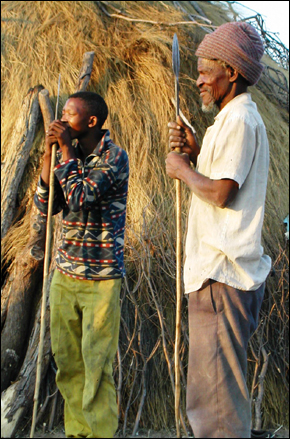

Two of Qoroxloo’s grandsons were the first ones back home inside, where they remain to this day. “As usual the government is doing everything it can to see to it that we resist from going home,” Galmomphete recently wrote me, in a note about life in the Kalahari that understandably took some time to reach the outside world, “but that’s not a surprise. We will keep fighting.”

In the note he described a recent hunt with his brothers. The three young poachers were joined by Mongwegi, Kalakala and Tshokodiso—the men who tracked down and recovered Qoroxloo’s body and who dug her grave—and by Mohame Belesa, her husband. “As it is our custom,” he wrote, “we went hunting thinking of the people in Metsiamenong because we felt we had to do something for them.”

The hunters chased down and killed two gemsboks and distributed the meat. Bushmen ate the flesh from one of the Kalahari’s most desert-adapted antelope, a beast that survived by digging up the moisture embedded in roots and tubers and leaves. The feast and reunion and dance in the night helped close the circle once more, reconnecting those returning home with those who never left. It re-knit the complex ties of a society that had been interrupted for five years. It felt good to be back home, wrote Galomphete, “after such long time having been denied the opportunity by the government. We really enjoyed that moment.”

I had been invited, and would have very much liked to join them. Over seven years in southern Africa I had grown fond both of the Kalahari and of Botswana’s predominantly decent people. To Botswana I had dragged my girlfriend, where we conceived a child, become engaged and raised our daughter. When work ended and my family moved home to America, I left an off-road vehicle and camping equipment behind, with plans to visit again and again. Then, one day, return became impossible.

After four decades as the exceptional shining example of African democracy, citizens became anxious their country was “heading for a dictatorship.” Even the jovial best-selling writer Alexander McCall Smith, creator of Precious Ramotswe, spoke up against Botswana’s policies in the Kalahari. In response the government began to label its critics as “enemies of the state.” Church leaders grew “afraid of making public comments for fear of being accused of being members of opposition parties.” President Mogae expelled a University lecturer as “a rogue” because he questioned the Bushmen evictions. Eventually, Mogae targeted 17 critical academics, human rights activists, and journalists from the UK, the U.S., Australia and Canada, and on that blacklist I found my own misspelled name. Until that list is revoked, I am left with the last memories of these defiant people.*

One evening at dusk several of us walked a quarter mile to pay respects before three unmarked piles of sand. The sky blazed orange and purple against thin distant clouds. Moving from one to another in turn, Mongwegi pointed out where Moeti, Gaoberekwe, and Qoroxloo lay buried. No animals had disturbed her grave over the last twelve months. The elements had smoothed the sand surface, but thorn branches still arced across it as a barrier to scavengers.

Jumanda shook his head. “In here are these three graves from five years,” he said. “And during that time, how many dozens of young men and women have we buried outside the Reserve? How many died out there and were unable to come home?”

Suddenly Mongwegi closed his eyes, threw back his head and cried out “to the spirits of these ancestors” to “continue to guide the living. To give strength to us. To show us the way when we become confused and have doubts.”

We turned in the silence and walked slowly back toward the fires and the laughter of Metsiamenong.

On that same trip, I spent a night in the eviction camp, Kaudwane, outside the Reserve. Hundreds still lingered there in purgatory, hating the place but too fearful of government threats to leave. I arrived there with Roy Sesana and the FPK legal team, who reassured the Bushmen that the High Court had ruled on five counts that they had been wrongfully, illegally, and unconstitutionally forced from the Kalahari and deprived of their livelihoods and homeland. They were free to return to the place they still called home. At this news the Bushmen jumped up and danced and clapped excitedly, and their wide eyes shone in disbelief.

Later, as the initial joy subsided and reality set in, a few asked if the government would again provide them water inside.

The Bushmen attorney, Gordon Bennett, slowly shook his head and looked down. On that count, he conceded, the High Court had ruled termination and destruction of water was legal and constitutional. Botswana would not restore it. But he planned to negotiate a compromise with them.

Upon translation, the Bushmen fell silent.

An hour after hearing the legal decision, two dozen Bushmen gathered beneath a shade tree, squatting on their haunches. As each spoke, the others listened. Some gestured, shook their heads, or drew in the sand with sticks.

I sat near a young Bushman named Kelejetseeing Moloreng. His family raised him in Mothomelo, but he left the Reserve as a teenager after officials destroyed the borehole. He now had a wife and child, and wanted to bring them to what he still considered to be home in the heart of the Kalahari. I pointed to the discussion and made a questioning face.

“The men, they are talking,” he said in the halting English he had picked up outside the Kalahari, “about water, how to get the water.”

Two of his friends elaborated. Men were debating distances, the limits of mobility into the Reserve, how much water they could carry and what the government might allow. Women worried about the status and distribution of the wild food growing inside.

“Some we eat,” explained Moloreng, “others we drink. They are divided. The food has water inside it.” I asked the men if they planned to return home. They vigorously nodded their heads, but their eyes left room for doubt. Some had previously been beaten for hunting. Most had been dependent on government services all their lives. “When it doesn’t rain, it is a problem,” said one.

“We grew up with it provided,” added another, “and here was always a tap.”

“But some of your people have never left the Reserve,” I observed.

“Yes,” said Moloreng, looking away for a moment, and then back at me. “They are strong. We are young. We go in during the wet season, when it is green. But during the dry season –” his voice trailed off.

I scribbled his words down into a yellow pad. He watched my chicken-scratch, smiled, and asked what I was doing. For decades out in the Kalahari, Bushmen had grown accustomed to anthropologists and wildlife researchers working on dissertations, but in recent years the foreigners with cameras, recorders and notepads grew increasingly rare. Perhaps the romantic mystique and novelty was wearing off, and evicted Bushmen were becoming just like 40 million other deracinated people. I explained that I wrote about drought and the struggle over water, and how what unfolded here may foretell what occurs in nations beyond Botswana’s borders.

The connection to people far away seemed to cheer him. “Yes,” he said. “Put this into a book, so the world can know about us and what was done to us. And we can tell the story to our children.”

“Where will you tell it to them? Here in Kaudwane?”

“No,” he answered. “Inside. In the Reserve. In our home.”

“How will you live there?”

“The old,” said Moloreng. “They know.” He fell silent for so long I wasn’t sure he would continue. Then he added in a quiet voice, “They know how to live without the water.”*

The old may know but they are dying faster than the vast wild places that forged their existence, taking with them strategies about how to adapt to a hot, dry, and unforgiving world.

The rarity of the last free and autonomous Kalahari Bushmen can make them seem precious; it can lead us to romanticize them as Rousseau’s ‘noble savage.’ Yet that, I think, would diminish Qoroxloo’s life and death. She was neither savage nor superwoman but rather a pragmatist who knew exactly where she was and thus who she was. She knew how to live and when to die. She successfully resisted eviction armed with nothing more than the intimate knowledge of her community and her place. And her nobility emerged when the stress from nature’s finite limits was compounded by official force, whereupon she did what any mother would do in such circumstances. Cut off from water, confined to a small perimeter, she denied herself week after week so that her family could endure. During her defiant existence Qoroxloo left a legacy as rich and potent as the rock art of her ancestors. Through perpetual drought and a protracted siege she revealed glimpses of a pragmatic Bushmen code of conduct.

Every society lives by a social contract, from religious authoritarian “thou shalt not” laws of the Ten Commandments or the Koran, to the secular democratic “government shalt not” protection of liberties under America’s Bill of Rights. Perhaps because theirs remained unwritten, the Bushmen’s code of conduct had the distinct advantage of being simple, durable, flexible and adaptable to aridity. Then again, it had to be. Without any hierarchical police enforcement, their lives were governed by voluntary and egalitarian interactions and by the authority vested by in the Kalahari itself.

In seeking out Bushmen to unlock a secure path through the age of permanent drought, I first had to get past barriers of lingering mythology and ideology. I am not immune to romantic sentiment. I want to believe, like Rousseau, that dissidents like Qoroxloo and indigenous people on every continent are innately one with nature, that they are more ethical than the rest of us, that they have a built-in tendency toward restraint which somehow made Bushmen, as one colleague put it “the original conservationists.” By this reasoning the Kalahari Bushmen would not squander opportunity or trust. They would avoid the stupid, selfish, reckless, destructive, wasteful, divisive, and shortsighted mistakes that the rest make outside the reserve, especially regarding something so fragile and magical as water.

My inner skeptic has persuaded me otherwise. I hope my lost naïveté reveals less a cynical pessimism than realistic hope based on universal egalitarianism. In any case the unvarnished anthropological record of human nature shows our species’ behavior does not vary by race or ethnicity, only by externally imposed social, ethical, political, and physical constraints. With no such limitations, each of us looks out for his or her personal interest—using others or exploiting the environment—until power corrupts us absolutely.

By now it should be all too clear that in a dry, hot world, water equals power.

So, given unlimited access to borehole technology and unlimited fuel to pump and deliver water, Bushmen would likely invite upon themselves levels of trouble, depletion, and exploitation from which they would most likely never recover. Just like us.

If our competitive demand for scarce water drives us apart and escalates tensions, this same finite supply of freshwater is also itself what ultimately drags us back and binds us together. We may not like the rule of increasingly scarce water, but at the same time we cannot escape it. And Qoroxloo’s band demonstrated how to embrace that reality. Her fundamental rule of adaptation was not to organize and mobilize physical resources to meet expanding human wants, but rather to organize human behavior and society around constraints imposed by diminishing physical resources.

To restate the reality of mitigation: We don’t govern water; water governs us. *

What did that mean in practice, for Qoroxloo’s band, and for us? We have seen how the scarcity of water governed all vital decisions: who and why to trust; where and when to disperse; what to eat; how much to consume; which plants were burned for fuel, used for construction, or gathered to drink. A water-secure diet emphasized diversified, nutritious, drought-resistant, and moisture-rich permaculture over tastier, storable, transportable bulk food, and was harvested nearby at peak water-ripeness. Since tastier feedlot cattle could not survive droughts, hunting favored desert-adapted game species whose juicy meat concentrated metabolic water. Health, sanitation, and medical decisions adroitly embraced aridity to convert waste into fertilizer, establish a buffer zone from disease vectors, and provide treatments from the concentrated oils of plants.

Unrestricted liberty allowed dispersal to more abundant water resources, reducing ecological pressure and political stress; and rewarded each individual for drawing on his or her unique knowledge of water extraction from a diversified portfolio of strategies.

Creation was not vertically ranked or segregated by species but rather shared the increasingly arid landscape while competing for its water resources. Manufacture of luxurious vanity items encouraged competition and reserved water for more urgent needs. Trained from childhood to avoid evaporation and leaks, Qoroxloo’s band developed their technology in the service of water, sealing it from the hungry sand and sheltering it from the thirsty sun. Rivalry over scarce water resources has always existed, but against primal instincts toward zero-sum violence our interdependence encouraged voluntary exchanges among networks that efficiently spread out risks while rewarding conservation both within and between bands. Conservatives call these informal markets while liberals see a reciprocal system of egalitarian barter.

Regardless of ideology, such exchanges emerge only when a society collaboratively agrees to define and defend a water resource that could be divested. Rain belongs to everyone and everything, but Bushmen honored long-standing individual and group rights to water resources: a sip-well, a pan, a buried and labeled water canteen, a field of tsama melons, a grassy hunting territory favored by eland or gemsbok, a wild cluster of fruit or water-filled trees growing along a seep line. Extending rights beyond kin to strangers not only reduced short-term hostility and resentment, but also helped expand an informal safety net of grateful recipients — a reliable form of drought insurance.

The principles or collective code that worked for Bushmen can be adapted outside their reserve. After all, whether it pulses between a competing heart and brain, sinks down in the shared aquifer beneath our fenced-off private property, or flows in the common currents that run along or across our walled-off borders, water is quite literally the connective tissue that links and rules our fates. Only this magical glue makes us collaborate to endure drought conditions at every level.

If we are to prevent dehydration, domestic strife, or degeneration into the ruthless Hobbesian/Darwinian scenario—recall those baboons around a waterhole or those first colonists at Roanoke or Jamestown—and if we are to avoid testing the nightmare hypothesis of a trans-national water war, then we need to derive a system like that which for millennia sustained people in the Kalahari.

Two-minute video “preview/trailer” of Heart of Dryness

Read more excerpts from Workman’s book featured on Circle of Blue here.

_____

* Footnotes

Dikarabo Ramadubu, “Professor Good Gone for Good,” Botswana Guardian, July 29, 2005.

Keto Sewai, “Government Slaps Visa Restrictions on Critics,” Mmegi, March 29, 2007; “The 17 affected individuals are: Steven Corry, Mirriam Ross, Fiona Watson, Jonathan Mazower, Janie Workman, Jonathan Reed, David White, John Walsh, Oliver Duff, Karin Goodwin, Carol Midgley, and Jonathan Simpson – all from the UK. The listed Americans are: Rupert Isaacson, Eric Grossberg and Tom Price; while Ian Taylor is an Australian and Daniella Stor is Canadian. At press time, Mmegi had been able to establish that four of the Britons – Corry, Ross, Watson and Mazower are all from Survival International (SI), government’s well-known nemesis in the CKGR saga.

Seven of the people in the list are journalists. They include Simpson, the respected world affairs editor with the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC); Financial Times of London’s South African correspondent, Reed and its African editor, White; Price, a highly respected American freelance journalist who often contributes to major publications such as the Los Angeles Times. Other journalists are: Duff (Independent – UK), Goodwin (Sunday Times – Scotland), and Midgley (The Times – UK).

Taylor is an Australian academic who previously worked as a lecturer on African Affairs at the University of Botswana. He co-authored a critical paper entitled “Presidential Succession in Botswana: No model for Africa” with Professor Kenneth Good. Speculation is rife that that paper, which Good was unable to present, led to his unceremonious deportation from Botswana. American Isaacson is known to be with the Indigenous Land Rights Fund, while Grossberg is suspected to be associated with an organisation that deals with conflict-free diamond issues. At the time of going to press, Mmegi had not yet established what Stor, Workman and Walsh do.

EPILOGUE: WHAT WOULD BUSHMEN DO?

In a seminal chapter of A Sand County Almanac called ‘The Land Ethic,’ Aldo Leopold eloquently argued how the “extension of ethics is actually a process in ecological evolution.” The evolving process or “ethical sequence” rippled outward, more inclusively with time, from: 1) personal conduct codes like the Ten Commandments, which guide relationships between individuals; to 2) social conduct codes like the Golden Rule or US Constitution which guide and govern the relationships between people and society; to 3) natural conduct codes, still emerging and undefined, which integrate humans with our complex life support system. Leopold focused his analysis toward this third category: An ethic, ecologically, is a limitation on freedom of action in the struggle for existence. An ethic, philosophically, is a differentiation of social from anti-social conduct. These are two definitions of one thing. The thing has its origin in the tendency of interdependent individuals or groups to evolve modes of co-operation. The ecologist calls these symbioses. Politics and economics are advanced symbioses in which the original free-for-all competition has been replaced, in part, by co-operative mechanisms with an ethical content.

Matt Ridley, “Ecology as Religion” in The Origins of Virture.

Sometimes ownership rights bore marks as obvious as a notched arrow or a labeled water canteen; more often than not, the ownership information was conveyed orally among those who asked permission.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!