Hidden Waters, Dragons in the Deep: The Freshwater Crisis in China’s Karst Regions

Yunnan Province is a microcosm of the challenges facing China’s vulnerable freshwater supply. Severe water pollution and shortages stand in the way of ongoing economic growth.

A farmer outside Qibudi in China’s Yunnan Province surveys his field. Although it has been raining for days, the same field, where karst stone is beginning to poke through the topsoil, turns dry for eight months of the year. He carries household water three times daily from a hillside pond. He and his elderly father make due on six buckets of water each day. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

By Christina Larson, Special to Circle of Blue

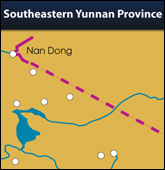

In the southwest corner of China, a land of towering mountains and deep gorges not far from the border of Vietnam, is Shi Dong, the Rock Cave. It is here, 800 miles west of the Pacific Ocean, in an area so remote that people often settle in villages with no more than a few dozen homes, where the Yang Liu River disappears underground.

For more than 20 miles, the river flows beneath the surface of the earth, coursing through dark caverns and crevices, unseen and unknown to those who live above, its precise path a mystery. It emerges again through the mouth of a second cave, Nan Dong, the South Cave.

These two openings in the earth, where the Yang Liu River slips into and out of the shadows, mark the point where a fluvial region rich with surface streams meets an unusual geologic formation of soluble rock layers known as a karst landscape. It is also a fateful human dividing line, a place where China’s desperate confrontation with water scarcity, industrial modernization and pollution come into clear focus.

China’s vision of assuming a greater place on the world stage and prospering in the 21st century — goals it impressively displayed at the 2008 Summer Olympics and at other global events since — depends in large measure on its capacity to fit thriving human settlements into a severely damaged landscape where water is scarce, inaccessible, or often too dirty to use. More than 400 of China’s 600 largest cities experience water shortages, according to United Nations assessments. Three-quarters of China’s rivers and lakes are dangerously contaminated by municipal waste, as well as industrial and agricultural pollutants. The World Bank estimates that by 2020 water stresses in China could create up to 30 million environmental refugees, people who must move from their homes in search of one of the most basic necessities for life.

Just like the polluted waters of the Yangtze River, the eroded hills of the Loess Plateau and sandstorms whipped up in the deserts of Inner Mongolia that pummel Beijing every spring, the Shi Dong and Nan Dong caves of Yunnan Province represent the front lines of China’s fresh water crisis. Studies of China’s southwest karst region indicate the water beneath the surface is contaminated with bacteria, chemicals and sediments that drain off the land. Moreover, the region’s porous landscape makes securing a steady supply of water for agriculture and household use an often daily challenge.

The question that confronts the nearly 100 million people in Southwest China’s karst region, and 1.2 billion other Chinese citizens is this: Can the economic miracle that has lifted 450 million people out of poverty in a generation continue to advance when so much of the country’s natural treasury, especially its storehouse of fresh water, is so depleted?

East Mountain Plateau

At least a portion of the answer can be found in places like the East Mountain Plateau of Yunnan Province. On one side of the plateau, where the Yang Liu River rushes above ground in a narrow valley, people who live nearby can walk to its banks to get water. They can also dig wells, which at a certain depth will hit the water table. The land here is lush, with rice paddies tucked into mountain valleys.

But on the other side, the karst side, the water runs beneath their feet through a honeycomb of porous rock, in places more than a thousand feet below ground. People living on the surface of the karst formation have almost no way to reach the river. They cannot see it or discern its course. In some places the water is close enough to the surface for rudimentary wells to be drilled, though few would be successful because the shafts usually fail to strike the precise place where the water flows. In most other instances the water is too deep beneath the surface for wells to be drilled with the simple tools and resources available in this isolated region.

The consequences are clear. The people who live here, where the water runs beneath the earth, are among the poorest in China, earning an average of $80 annually, according to several studies. For much of the year, their fields are parched, their gardens dusty, and their hopes for a better life run dry.

Not far from the village of Qibudi, a small settlement of a few hundred people in the southeast corner of Yunnan, a road winds up the slopes of the East Mountain Plateau. The horizon is jagged, the outline of distant hills wrinkle at unexpected angles characteristic of karst landscapes. The villages along this road have limited access to water and few options for growing crops. In this corner of Yunnan, farmers tailor their crops to what the landscape allows. In some of the lusher valleys, which are not karst landscapes and where water is more plentiful, rice is grown, with plows drawn by sturdy water buffalos.

But on the drier hilltops, the options are more limited — and the people are poorer. Fruit trees require less water than rice or vegetable fields that must be irrigated, and so there are many small orchards tucked into the slopes. Tobacco is grown as a cash crop where it can be, though it requires plastic sheeting to be draped across fields to preserve what little moisture is in the ground. Both fruit and tobacco are highly labor intensive, requiring crops to be picked by hand.

Members of the Putu minority group wear traditional clothing in the karst highlands near Mengzi as they haul their crop of plums bound for market. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

One afternoon last May, seven ladies were seated by the roadside selling plums. Their woven baskets, full of green fruit, were draped with broad ferns to protect the plums from the scorching sun. The women, members of the Putu minority group, wore traditional bright orange and red embroidered skirts. One was stitching a scarf. They were waiting.

But the truck expected to pick up their fruit to take it to market did not come. An hour went by, and then another. The ladies could do nothing but wait. And the plums would spoil if they did not reach market in a couple of days.

The reason the truck never came, it turned out, was that the road was under construction, a frequent occurrence in this rugged landscape. Eventually, what arrived was not a vehicle, but an impromptu caravan of day laborers, hired by a market wholesaler, and riding donkeys, motorcycles and carts. This way, at least, they could traverse the torn-up roadways, whereas a truck could not. The men began strapping the fruit baskets to their motorcycles’ seats and donkey saddles.

One man, 30-year-old Che Qi Xiu, was driving a donkey cart. He also had a small farm plot nearby, but limited water meant the fields were barren a portion of the year. In the wet season he grew vegetables. And in the dry season? He shrugged. “Let them dry.” It had never occurred to him that it could be otherwise.

Plenty and Plunder

There are few places in the world where the differences between nature’s haves and have-nots are more evident than here, where the porous karst landscape meets more solid ground, creating a stark dividing line between those with access to water and those without. The border itself is unmarked, by a fence or railroad or ocean. There is no visible boundary — it is simply that, where the Yang Liu River disappears underground, life changes. Because this boundary is unseen, its significance is often overlooked, by governments and by the people themselves.

In Yunnan Province, like other poor and remote regions of China, families have lived for generations with little sense of choice or recognition that life could be different. Many families moved to Yunnan’s karst region centuries ago, at a time when the landscape was somewhat greener, before the Great Leap Forward of the late 1950s and early 1960s stripped the hillsides of vegetation.

That vegetation had previously locked moisture into the area’s soil and shallow bedrock, making farming more tenable. But when history conspired to change the ground beneath their feet, the residents of these regions did not have anywhere else to go. And so they accepted their fate and have tried to make do with less.

The Chinese government is not ignorant of the great challenges it faces, nor are the Chinese people. According to a 2009 poll by Circle of Blue and GlobeScan, a global public opinion polling firm, 67 percent of Chinese respondents said water pollution was a very serious problem in their country, and 59 percent said they are very concerned about the lack of safe drinking water.

Yet, what makes this region unlike so many other water-scarce areas of the Earth is that geology is as important as rainfall in determining the level of water scarcity. In this surprisingly rain-rich region, during the wet season water falls in sheets from the sky. But the monsoon rains do more than fill rooftop cisterns; they also, unfortunately, scrub soil from the rock, drain fertilizers and farm chemicals from the fields, draw up the human and animal wastes scattered across the land, and then pour down into innumerable crevices and holes in the earth, vanishing from sight. The water moves so fast off the surface that what’s left is a landscape of barren rock, in many places as dry as China’s great northern deserts.

A Huge Terrain of Surface and Underground Caverns

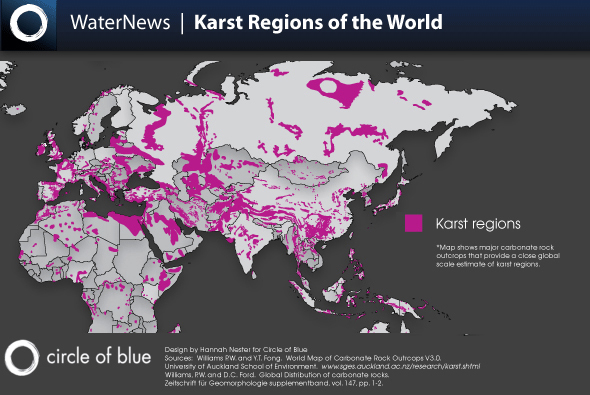

The karst belt of southern China stretches through eight provinces – from Guangxi and Hubei in the east to Guizhou, Sichuan, Yunnan and parts of Tibet in the west. The region encompasses nearly 200,000 square miles, larger than California, and is home to between 80 million and 100 million people.

A guide paddles through the cavernous tunnels of Nan Dong, where the Yang Liu River resurfaces after journeying some 20 miles underground. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

In part because of the karst landscape, the region is also one of the poorest stretches of China. Of the country’s 31 provinces and prefectures, Yunnan and neighboring Guizhou Province have the 29th and 31st lowest per capita incomes, according to the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics.

Karst geography, moreover, is not just a challenge for remote areas. In Kunming, the capital city of Yunnan Province, a new airport is under construction. While planners hold it up it as a model of green construction, the site straddles a karst landscape, which presents serious challenges to such large-scale construction projects. Leveling the landscape here to build the new airport has allowed large amounts of sediment to flow directly into the city’s underground water supply.

In other parts of the country, the consequences of construction on rivers would be apparent, and measures could more easily be taken to avoid harming water supplies. But here, where rivers are hidden underground, and there are so many direct pathways between the surface and the deep channels, the potential to harm groundwater is much greater.

To what extent is geography destiny? The soil in China’s karst region is typically poor for agriculture, because much of it has washed away following widespread deforestation. Growing crops in limited topsoil and wrapping fields around stony hillsides is extremely labor intensive. These challenges disproportionately affect minorities in China, who already live in some of the world’s most remote and ecologically fragile areas.

“Geography contributes to poverty in many ways,” explained Amelia Chung, who has worked extensively in participatory approaches to rural development in southwest China. “Not only lack of water, but mountainous terrain that makes transportation costly and roads difficult and expensive to build….[that’s] related to lack of educational opportunities as well.”

Water Plentiful, but Untouched, Unused, Unseen

Karst landscapes are not unique to China. They also span significant areas of Asia, Europe, and the Americas. Scientists estimate that karst covers some 15 percent of the Earth’s land mass, and that such areas are home to as many as 1.5 billion people, a quarter of the global population.

These regions represent an underappreciated facet of the global water crisis — but also are ripe for international collaborations and potential solutions. The problem is not lack of rainfall. In Southwest China, summer is the monsoon rainy season. But the bedrock in the karst landscape is so porous, like a sieve, that the torrents of rain that fall on the ground quickly seep through and disappear underground, most often beyond the reach of farmers in a region where food and crop production is the most important means of economic sustenance.

But to those who call this place home, the landscape’s unusual character, and the constant search for water, are facts of life. In some villages, simple fixes make a big difference.

Three years ago, for instance, a young farmer named Tian left his home in the village of Qibudi during a time when the hillsides were brown. The fields were parched and barren, with little water for irrigation. The roads nearby were quiet, except for the occasional voices of old women, wearing traditional blue headscarves, and small children, who had stayed behind.

The young men were leaving to find work in factories. There was little money to be made. Across China, some 350 million people — more than the population of the United States — are expected to move from rural areas like this into fast-growing cities in the next two decades.

The 22-year-old Tian, skinny with long dark bangs falling across his gentle eyes, followed other young men in his village to work in a factory in southern Guangdong Province. He doesn’t know precisely where he went; nor did it matter. He was simply far from home. He kept in contact with his parents with occasional calls on a pre-paid cell phone.

After about a year, he got a call from his older brother: his parents were sick. Tian returned home in time to watch them die. He took over their small farm plot, where they had grown corn and other vegetables. The village was, in many ways, the same. He was comforted by small familiarities: the curve of the main road that looped around the village; the clackety-clack sound of goats’ hooves as they wandered through narrow cobbled lanes between low brick homes.

But there was also a welcome change, a simple upgrade that improved the prospects for young farmers. In the center of the village, a manmade pond had been constructed by the government and fed by a pipe from a distant spring. Villagers could now pay a small amount per hour to pump water from the pond to irrigate their fields.

The village’s water situation, while improved, was still precarious. For about two months a year, at the end of the dry season, the pond is empty. And even when the pond is full, Tian’s neighbors worry that leaks have developed in the pipes, and it’s not clear when or if the government will fix them.

Yet, the construction of the pond demonstrates how a basic public investment can provide the little bit of water that has brought revived economic opportunities to the village. There is more greenery, more diverse crops, more money and more options.

In the year since the pond was built, some villages were able to afford an upgrade from clay to brick homes. And Tian said he now wanted to make a life in Qibudi, not the big city. So long as he and his new wife, and their infant boy, can continue to farm their land, they prefer to stay here and maintain the life they have known. So long as they have water.

Hours of Fetching A Drain on Muscles and Lives

Most landscapes on earth are formed by erosion, where the hillsides are worn down by wind, rain or ice. Rain carves away landscape. Wind slowly shapes rocks. Glaciers grind away the hillsides.

In rural Yunnan Province outside Mengzi basin, farmers plow rice paddies with water buffalo and build elaborate systems to slow water’s inevitable flow downward and then underground. Nearby, tobacco plants are shrouded in plastic to conserve water. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

But karst is unique in that the peaks and valleys of the terrain are formed by the soluble rock literally dissolving away. This has produced some of the most spectacular landscapes in Asia — from the dramatic peaks of Guilin to the jagged islands of Vietnam’s Halong Bay.

In karst regions, those residing in villages such as Qibudi are unable to access the water they need, even in a deceptively lush looking landscape. Villagers have no way of locating underground rivers, or even know that they exist. And so they make due as best they can — collecting rain in rooftop cisterns, or spending hours walking to ponds or distant springs.

One afternoon in late May, a farmer outside Qibudi surveys his field, clasping a broad straw hat in his hand. He says he is unmarried and lives with his elderly father. Small green shoots were beginning to poke through the red soil in neatly planted rows. The sky is dark, as though another storm is looming. It has been raining for days. Yet, the same field is a different world in the dry season, which lasts for eight months of the year.

When there is no rain, the farmer draws water from a rickety pump the government has installed. Before that, like Tian, he walked long distances. “The water we use at home had to be carried from elsewhere,” he remembers.

Finding water often means walking for hours a day to and from one of the few springs on the plateau, and carrying water home. “The landscape is like a funnel; it is very difficult to catch water,” said Yu Xiaogang, a former government scientist who in 2000 founded Green Watershed, a Kunming-based NGO devoted to empowering citizen involvement in water management and policy-making.

Contaminated Supply

Even when water is drawn from this region, its quality is often impure. In karst regions, the natural filtration system does not apply. “Pollution is a very big problem … underground polluted water is very difficult to clean,” said Xiaogang. The two great challenges regarding water anywhere — ensuring supply and quality — are dramatically heightened in karst regions.

Shi Dong, known as the Rock Cave, is where the Yang Liu River disappears into cavernous channels on its hidden journey underground. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

Karst terrain, above and below ground, is formed from rain dissolving limestone and producing caves, sinkholes, channels, and fissures that fill with standing and moving water. In southwest China, government hydrogeological surveys and scientists, including those at the Institute of Karst Geology in Guilin, have documented more than 3,000 underground streams with a total length of more than 9,000 miles and capable of carrying 25 billion gallons of water a day. In essence, an underground river system functions as the vast drainage sink for everything that is deposited on the surface — farm chemicals, animal and human wastes, toxic manufacturing compounds, lubricants, oil, paint, whatever.

Though the underground water supplies of Southwest China have not been extensively analyzed, the available studies conducted by researchers in Yunnan Province coupled with other research on karst water resources across China indicate considerable cause for concern about the quality of the groundwater. Various concentrations of fecal bacteria, nitrates, organo-chlorine compounds from agriculture, toxic heavy metals, arsenic, herbicides and other chemical contaminants have been found in the water.

The consequence on the health of residents exposed to the dirty groundwater is not fully known. In one joint Chinese/U.S. research effort, for example, researchers from Western Kentucky University and China’s Southwest University documented nitrate levels in karst spring water from several provinces of southwest China that exceed levels the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency considers safe for drinking water, in some cases by more than 10 times. They also found concentrations of pesticides, including the triazine-class herbicides that include atrazine, a popular weed killer used by farmers, although those were within levels considered safe by the E.P.A.1

Like other agricultural karst areas, potentially pathogenic bacteria from human and animal waste are essentially ubiquitous in the karst groundwaters of Southwest China, perhaps posing the largest threat to public health.

“The residence time in a karst system is often short, which provides limited ability for self-purification and for micro-organisms to die off,” wrote Jiang Yongjun and Chris Groves, authors of one paper resulting from the work. “The large number of interconnected fissures in a karst system make pollution inputs spread quickly and widely.”2

In short, contend Jiang, Groves and other karst scientists, solving water contamination problems below ground means thinking carefully about how China manages its land use in karst regions.

A Karst Specialist in China

In the 20th century, China’s historic turning points also marked environmental milestones, for better and worse. For instance in the late 1950s, Chairman Mao’s Great Leap Forward economic development campaign included an unsuccessful attempt to match England’s steel production by building backyard furnaces that not only resulted in poverty and mass starvation, but also stripped trees from hillsides across China and badly damaged the land.

Many regions have since recovered their greenery, but karst landscapes still bear the scars of recent history as the topsoil has been slower to recover, making it doubly hard for vegetation to grow back. Another environmental challenge in limestone bedrock areas is that the rocks dissolve in water and wash away, leaving little behind to form soil.

More recently, the launch of China’s Reform Era in 1979 not only paved the way for vast economic shifts, but also enabled new and extensive international scientific collaborations that promoted Chinese and western scientists to come together to share data and solve common problems for the first time in the modern era. Environmental concerns have been among the shared priorities.

Rarely can the growth of a scientific field be attributed to a single man as it has in China, where researcher Yuan Daoxian did for the study of karst in China what Watson and Crick did for the study of DNA: he lit the path forward. Although generations of poets and artists had attempted to explain caves’ origins and mysteries, before Yuan scientific knowledge was limited. Yuan led extensive geologic surveys of karst regions, probing how geology related to water supply, and gathered around him a team of dedicated scientific pioneers who strived to see that their academic work had real-world impacts for improving the lives of those in China’s water-scarce regions.

In short, Yuan, a sprightly and unassuming man with an unusual personal history, has been pivotal in accelerating international interest and collaboration in karst research.

Yuan was born in Zhejiang Province, in eastern China. The fact that he later studied in central China, where his imagination was inspired by the serrated landscape of the country’s interior karst regions, was an accident of history. Because of the fear that Japanese air raids would strike China’s eastern cities during World War II, his parents sent him to middle school in Chongqing, in central China. Chongqing is today known as the fastest growing metropolitan area in the world. But at that time, in the 1940s, it was a relatively quiet provincial capital.

China’s civil war ended in 1949, and Chairman Mao declared the founding of the People’s Republic of China when Yuan was in college. He graduated from Nanjing Technological Academy of Geological Surveys in 1952. Those early years of the new republic were a hopeful time in Chinese history, and Yuan joined in service to his country as a hydrogeologist for Yunnan Province. Over the years his assignments afforded him reason to travel throughout Yunnan, Guangxi and other parts of China’s most significant karst regions.

In contrast to civil engineers, who built dams and bridges, the connection between the landscape and human concerns was always at the root of Yuan’s work. “At that time,” he remembers, “most of our work related with finding drinking water for local farmers, for irrigation, for water resources for irrigation and help engineer geological work.” One of the few exceptions was a project that brought him to Tibet, where for three years he oversaw efforts to bring electricity to the Potala Temple, at the request of the Dalai Lama.

In the course of his work, Yuan realized that the geology was intimately connected to water issues. He began to seek resources and like-minded geologists to solve the problems he encountered. “In these [karst] regions, there is a shortage of drinking water, even with the high precipitation of more than 1,000 millimeters per year,” he explained in August 2009, at a conference in Kunming for karst scientists that he had helped to organize. “And then people suffer from the shortage.”

In 1976 Yuan founded the first karst research center in China, the Institute of Karst Geology in Guilin. During the reform period in the 1980s, he became a virtual one-man operation, organizing symposia and bringing international scientists on some of their first tours of western China to study karst formations and collaborate on joint research projects. Even well into his 50s, Yuan, who is now 76, was leading scientific expeditions into caves, dangling from ropes and muddying his boots to navigate slippery corridors.

Professor Yuan has trained many of the next generation of karst scientists in China, and maintains ongoing research partnerships with several universities, including Western Kentucky University. Their joint projects include developing new methods to trace the course of underground rivers. Most of the scientists working on karst issues in China today have some connection to Yuan, an undisputed pioneer.

For his part, Yuan views his contribution this way: “This is my duty to help the people still under the condition of the poverty, to help improve their life, I think, in the future,” he said. “And because I am older and older and training young people to succeed my work, I think it is a big job and a big area. I need many young people and I need continuous cooperation with foreign colleagues.”

U.S. Scientist Involved

Another key scientist active in water resources research in China’s karst areas is hydrogeologist Chris Groves, director of the China Environmental Health Project of the Hoffman Environmental Research Institute at Western Kentucky University. Groves, whose university is situated in another of the world’s most significant karst regions, first met and began to work with Professor Yuan in 1995. One of their early projects was an investigation into impacts of karst geochemical processes on carbon in the atmosphere.

“More modern research methods for understanding karst groundwater have in many cases developed in the West, but the intimate knowledge of karst landscapes is very good in China. There’s a natural collaboration,” he said, “Yuan Daoxian played a key role, because he was one of the few people that really made an effort to establish these international linkages.”

One morning in late May, Groves stood on a mossy rock just inside the mouth of Yunnan’s Shi Dong Cave. Some time ago, the Yang Liu River had flowed into this very cave, now a hangout where local teenagers smoke. But many years ago, the river shifted course slightly and carved out a different pathway nearby, forging a new tunnel where it now slips underground.

“Water has only one goal,” said Groves, pointing inside toward the deeper recesses of the cave, “to get down as rapidly as possible to the level of the water table. It will take any pathway available, expanding fissures, then shifting course again, whatever allows it to drop down most quickly.”

Twenty miles away is Nan Dong, the cave where the river emerges. Today it is a local tourist attraction, where visitors can take guided boat tours, their journey along a short stretch of the underground river illuminated by purple and green lights hung from stalactites. The link between Shi Dong and Nan Dong was first established in 1969 by a team of Chinese scientists. At that time, the state-of-the-art method for charting the course of underground rivers involved dumping massive quantities of salt — which changes water chemistry in a way that can be easily detected — into a surface river where it disappeared underground in a karst region.

The scientists hired a team of some 300 Chinese farmers to hike eight miles from the nearest road to Shi Dong cave with heavy backpacks, hauling 26,000 pounds of rock salt. They released the salt into the disappearing river that flowed into the mouth of the cave and later recorded where it flowed out of Nan Dong cave.

Though the experiment confirmed where the Yang Liu River started and ended its underground journey, the scientists still did not know much about the route the water took between the two caves.

Since then, more precise — and less labor intensive — methods have been developed internationally, and in China. One of the technologies whose use Yuan and Groves have helped to establish in China employs fluorescent dyes to trace underground rivers. These methods have been well developed in the United States and Europe, and through cooperative relationships are now used more widely in China.

The dyes are non-toxic, and since they are detectable in extremely low concentrations in cave water, are both environmentally sound and much more portable. This is significant because if scientists can readily trace underground rivers, they can assist local governments or NGOs in successfully locating wells or other infrastructure to tap these hidden sources and bring water to the surface for people who need it.

The government of Mengzi, capital city of Honghe Prefecture, located not far from the East Mountain Plateau, enlisted researchers at Yunnan University to help them locate subterranean water sources. The city was then able to tap into water that otherwise would have been lost in underground rivers. The increased availability of water has enabled rapid growth and population expansion in Mengzi, now a relatively prosperous urban oasis in the midst of an otherwise impoverished region.

Limit to Growth?

In China, the elemental significance of water has been understood since ancient times. The character for “water” forms the root of the character for “political stability.” Many regions of the country have temples built specifically to offer prayers for water. In China, as around the world, people have regarded water and its availability as so critical to human life that it’s been enshrined in ritual and art.

Today, the challenge to secure enough water is well known, especially since the publication of the seminal 1999 book, China’s Water Crisis, by journalist and environmentalist Ma Jun. In years past, American scholars such as Lester Brown asked, “Who will feed China?” Today the question put forth by Ma Jun and others is, “Will China have enough water to sustain its rapid development?” Desertification, climate change, the country’s steadily growing population, inferior or non-existent infrastructure, and rampant contamination make the answer uncertain.

Each year one-third of industrial wastewater and two-thirds of household sewage is returned to water resources untreated, according to studies by global NGOs and international aid organizations.

More than 75 percent of the rivers flowing through Chinese cities are unsuitable for drinking or fishing. Almost half of China’s surface rivers are so polluted that they are not even suitable for agriculture or industry.

Water scarcity concerns have also led to the use of industrial wastewater to irrigate farmland. In urban areas, 70 percent of drinking water comes from groundwater sources, 50 to 90 percent of which is contaminated by agricultural runoff, and industrial and municipal wastewater. Some 700 million Chinese people do not have access to safe water. In karst regions, all these problems are exacerbated.

Yet, the story of scientists like Yuan and Groves working in Southwest China also inspires hope for potential solutions. The hunt for underground rivers is one dimension of the global water crisis where increased scientific collaborations seem likely to bear fruit.

There is no doubt that China’s historical tide is rising. Economists predict that sometime around 2025, China will have the world’s largest economy. It has already become the world’s top auto market, its top exporter, its top polluter.

Superlatives come easy when talking about China. So do the challenges to China’s development. And one of the gravest obstacles is also the most elemental: the limited availability and accessibility of water. Will China have enough water to sustain its growth?

China’s leaders are now seeking to aggressively respond to the country’s fresh water crisis with huge public works projects. China builds the largest and most dams and water transfer projects in the world. The government is engaged in an astonishingly ambitious and, to some observers, ecologically risky plan to transfer water from the Yangtze River in the south to the northern Yellow River through an elaborate series of three planned canals.

China’s leadership tends to prefer technical fixes to increase water supply over more complex policies to boost conservation. However, far-ranging challenges require multi-faceted solutions. Today research is underway, in China and globally, to tap into the overlooked resources of the karst areas.

Collaboration between universities and governments on several continents could help bring relief to some of the most parched places on the planet. Moisture in karst regions does not need to be piped in from thousands of miles away, or boiled from seawater. The water is there to be tapped, within reach even if it’s so hard to grasp.

Christina Larson, a contributing editor at Foreign Policy, is a Schwartz Fellow at the New America Foundation. This is her first article for Circle of Blue. Keith Schneider, Circle of Blue’s senior editor, edited and contributed to the article.

Sources

1 Ted Baker and Chris Groves, 2009, Water Quality Impacts from Agricultural Land Use in Karst Drainage Basins of SW Kentucky and SW China. Planning for an Uncertain Future—Monitoring, Integration, and Adaptation, US Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2009–5049.

2 Jiang Yongjun, Wu Yuexia, Chris Groves, Yuan Daoxian and Pat Kambesis, 2009, Natural and Anthropogenic Factors Affecting the Groundwater Quality in the Nandong Karst Underground River System in Yunnan, China, Journal of Contaminant Hydrology.

Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

china is really vary beautiful place. i want to visit this place in my whole life 2-3 times.

Thanks for this very good in-depth article full of interesting information, joining social as well as geographical explanations.

have traveled many times to Yunnan and really appreciate this article.

For the bio diversity and beauty of Yunnan there is little in depth information both in Chinese and English. For such a multi climate/ethnic part of China it means still much to be done to protect what little is left.

Now tea, rubber, eucalyptus, and coffee farms destroy what pristine greenery is left.

Mining for the last 150 years has also done damage especially to waterways.

The drought the last few years has further tested her bio diversity.

Really hope that with more documents like years small changes might happen.