Higher Water Prices Needed Globally, OECD Says

A report from 30 of the richest countries in the world says raising water rates will help protect and maintain the precious resource for the future.

Water prices should rise to encourage less waste and pollution as well as to fund improvements to supply systems, according to three studies released by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

As fast-growing cities are expanding beyond the limits of their water supply, some experts argue that higher prices will delay the cost of expensive system expansions and maintain existing supply lines.

“Putting a price on water will increase the awareness of the scarcity and make us take better care of it,” said OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurria.

The OECD, a network of high-income economy countries, surveyed residential and agricultural water prices in each of its 30 members. A 2008 Global Water Intelligence/OECD survey of water prices in 261 cities found that Copenhagen had the highest combined water and sewer rates globally.

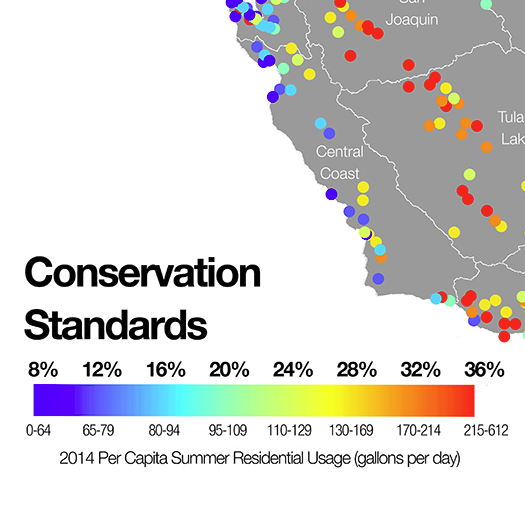

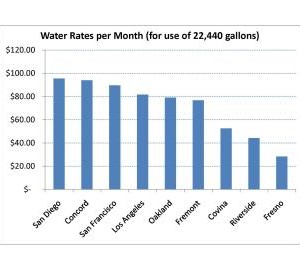

Though higher prices can lead residents to conserve, it can also bring financial instability to a water utility if price increases are poorly implemented. Many cities in the U.S. are facing revenue shortfalls because customers are conserving too much, according to a Circle of Blue survey.

Because price increases are publicly and politically unpopular, conservation education programs and rebates for water-wasteful appliances are common alternative measures utilities take. However, water conservation is not the only justification for higher prices. Many utilities need to replace aging infrastructure or install new treatment plants, but insufficient funding is a major obstacle.

This creates what is known as the low-level service trap.

Governments charge too little for water, leaving the utility short of cash to invest in the water system. Meanwhile customers are reluctant to pay for poor service and resist price increases, forcing the price to stay low. As a result, revenues are low and the government cannot improve the service.

“We were in a vicious cycle,” said Virgilio Rivera, a director of Manila Water, to the Guardian.

Manila Water, a private company, took over the water supply system in the Philippine capital in 1997 when the government service was privatized. The company raised prices to 30 pesos per cubic meter, up from 4.5, according to the Guardian. There was public anger at first, but Manila Water doubled the number of connections in the city by 2003. The city’s poorest residents, who used to buy expensive water from tanker trucks, now pay one-tenth of what they used to for water.

The OECD says that farmers also need to pay more. Agriculture uses roughly 70 percent of global water supplies and much of that is wasted through leaky pipes and inefficient irrigation techniques. Infrastructure improvements and conservation will be needed to double agricultural production by 2050–an increase in output necessary to feed the world’s growing population, the report states.

Source: OECD, Guardian

Read more from Circle of Blue about water prices and water usage in the U.S.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!