Cholera in Haiti — The Climate Connection

Tropical storm has exacerbated Haiti’s water and sanitation woes.

By Aubrey Ann Parker

Circle of Blue

After lying dormant in Haiti for half a century, a three-week-old cholera outbreak has killed more than 700 people and is advancing across the country. On Tuesday, the epidemic reached Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s capital and largest city, where more than a million people are still squatting in over-crowded tent camps and sharing scant latrines. Hurricane Tomás, meanwhile, struck Haiti’s shores on Friday, flooding vulnerable tent camps. Reported infections have climbed close to 10,000 cases — nearly doubling in the last week.

“I don’t think we are going to see the end of it any time soon,” Emmanuelle Schneider of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs told Circle of Blue. “It’s very contagious and it can spread fast.”

— Dr. Rita Colwell,

Cholera Researcher

Cholera, a water-borne disease, can spread rampantly when clean water and proper sanitation are not available, as had been the case in Haiti long before the January earthquake that killed 250,000 and displaced 1.6 million. But the damage from the earthquake, which hit hardest in Port-au-Prince, could be the compounding factor that allowed cholera to rise from the rubble.

Researchers, health officials and the media are all seeking answers to the same question: where did the cholera bacteria come from?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that the strain of cholera that is spreading in Haiti originated in Southeastern Asia. That finding prompted news organizations to focus on humanitarian workers as the source of infection, an assertion that medical specialists quickly discounted. A handful of activists, in addition, blame the outbreak on Haiti’s substandard housing since the quake.

But a number of researchers say Haiti’s cholera outbreak is related to climate patterns — the infection erupted and is spreading during an especially wet La Niña year.

“They have been fortunate in Haiti that for 50 years the conditions have been such that they haven’t had an intense increase in cholera bacterial populations,” said Rita Colwell, professor at the University of Maryland and former director of the National Science Foundation. “But they’ve had an earthquake, they’ve had destruction, they’ve had a hurricane. So the conditions would lead to a very high probability of an outbreak.”

She added: “I think it’s very unfortunate to look for a scapegoat. It is an environmental phenomenon that is involved. The reason we don’t know [the catalyst] is because the medical community is not receptive to climactic causation or correlation.”

The Climate Connection

Cholera is an intestinal bacterial infection spread by eating food or drinking water that has been contaminated.

Although rural areas experienced less damage from the earthquake, they were the first epicenter of the epidemic. The small communities along the Artibonite River, located 60 miles north of Port-au-Prince, have been using the river as a source of drinking and bathing water — until reports came that the river is the likely source of the outbreak.

“Cholera was originally in the Artibonite River,” Schneider said. “But people are very mobile, so they are moving from place to place, which is a trigger for the cholera epidemic.”

In the last few decades, great strides have been made in unlocking the riddles associated with cholera and seasonal climate patterns. Dr. Colwell was among the first to find that cholera epidemics flare up during the wet spring and fall seasons, when excess precipitation creates favorable environmental conditions such as increased salinity and warmer temperatures in areas already suffering from poor sanitation and lack of clean water access.

Colwell and her colleagues are studying 75 years of cycles in India and hope to have definitive parameters in the next few months. Additionally, using weather data from 1991-1992 and 1997-1998, they have shown that there is a correlation between cholera outbreaks in Latin America and El Niño climate patterns.

The intent of her research is to predict cholera outbreaks using the link between weather patterns, water surface temperatures and plankton blooms — all of which could be detected using remote sensing satellites. An early warning system for coastal dwellers would have been valuable for Haiti.

Afsar Ali, an associate professor of environmental and global health at the University of Florida, agrees with the environmental climate conclusion. He told the Tampa Bay News that the cholera outbreak is happening now, rather than immediately following the earthquake in January, because the water temperature is warmer. And since the first cases of cholera were reported in a coastal city, Ali believes that residents had longtime immunity, whereas the estimated 300,000 refugees who moved to the Artibonite region after the earthquake did not.

Prevention vs. Response

Even before the earthquake, there were risk factors for water-borne disease. More than 40 percent of Haiti’s total population did not have a source of reliable drinking water, according to a study by the United Nations. And nearly half of rural Haitians were defecating in the open, according to a joint study by the World Health Organization and UNICEF.

To prevent cholera, proper latrines and safe water must be provided to Port-au-Prince and the outlying communities. Although a vaccine exists, its ability to provide sustained immunity has not proven satisfying. Colwell argues that vaccinations are not the way to go. She urges for preventative measures, rather than reactionary.

“Millions get spent on vaccines,” Colwell said. “But provide sanitation and safe water, and you prevent more of the diarrhaeal diseases, including cholera.”

“Everyone is so endued with a high-tech solution — they want fancy water treatment systems — when, really, what is needed is to provide appropriate technology for clean water and sanitation.”

La Niña: Warm, Wet and Wild

The Category 1 hurricane that hit Haiti’s coasts on Friday brought with it gale force winds of 85 miles per hour. The wind and excessive rainfall have caused flooding in many parts of the country, and many fear that cholera will spread even more easily now with increased sanitation problems that could put raw human waste in the streets.

“Cholera is a disease that is spread by water,” Schneider, of the U.N., told Circle of Blue. “With the hurricane, there will be consequences on the epidemic because there has been a lot of flooding and washouts.”

Colwell, though, is convinced the epidemic will eventually weaken. As the waters in the Caribbean cool during the transition from fall to winter, Colwell expects the cholera to subside. When asked if she is worried about cholera reappearing in Haiti during next spring’s wet months, Colwell said it is quite possible since the Vibrio cholerae bacterium is native to aquatic waters. And, she added, if the disease makes its way to the Port-au-Prince refugee camps, it will accelerate the natural annual cycle by adding person-to-person transmission. But, for now, she’s optimistic that when the extreme weather subsides, so will the epidemic–as long as the public health system can deliver prevention as well as treatment.

“Unless the public health situation really deteriorates, the epidemic should subside” she said. “This happens year after year in Bangladesh and parts of India. If it follows the seasonal patterns, it will subside.”

“Claims will be made by various people that they have stopped this,” Colwell added. “But the fact is that it will probably be Mother Nature that brings the epidemic to low-level endemic conditions.”

Aubrey Ann Parker is a reporter for Circle of Blue where she specializes in data visualization. Reach her at circleofblue.org/contact.

Continued from above:

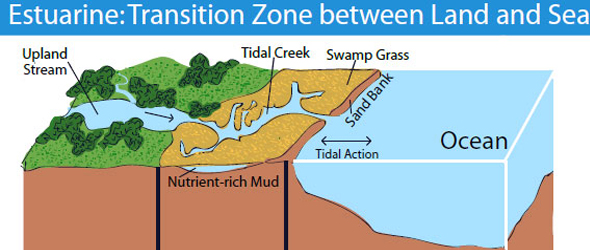

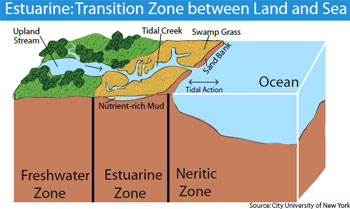

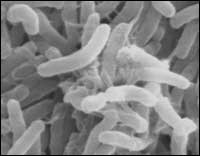

When Bacteria Wake Up

The warmer temperatures and higher salinity associated with rainy seasons are beneficial for cholera bacteria. First, when estuarine zones are nutrient-loaded from river runoff and stirred-up river basin sediments, the increased salinity aids cholera bacterial growth. Secondly, these favorable conditions can also trigger algal blooms, which serve as a food source for filter-feeding crustaceans — such as crabs, clams and oysters — and other zooplankton species. The cholera bacteria coexist with the crustaceans by growing on their egg sacks or inside their intestinal tracts. Thus, an algal bloom leads to a larger population of zooplankton, which leads to a higher concentration of free cholera bacteria in a body of water.

Cholera bacteria can then be ingested by humans, either through drinking contaminated water or eating raw contaminated seafood. The disease spreads when contaminated human feces gets into drinking water, usually through poor sanitation. Since cholera is dose dependent, infected persons early in an outbreak typically do not show symptoms, which exacerbates the silent spread of the disease.

But it’s not just marine and brackish water. Recent examples of freshwater sources contaminated with cholera after algal blooms include Australia, Germany and Zimbabwe. In these freshwater instances, increased salinity comes from calcium rather than sodium, as is present in estuarine zones.

“When you have flooding and you have turbidity stirring up the sediment, you feed the water column and you create opportunity for [plankton] blooms to occur,” Colwell told Circle of Blue. “And for those of us who have done studies, we know that these blooms occur seasonally and also in freshwater as well.”

Colwell, who this year was awarded the Stockholm Water Prize, has studied the link between cholera and climate for the last 30 years. Her research has disproven the long-held belief that cholera could only enter the environment due to a release of sewage, and has proven that there is a link between changes in the natural environment and the spread of disease.

She says that there is a correlation between environmental interactions and human health that much of the general public is failing to see. Seasonal cholera epidemics flare up in the fall and spring but taper as warm, wet weather subsides. And although Haiti hasn’t had a reported cholera case for nearly two generations, this fall has been extremely warm and wet, thanks to La Niña.

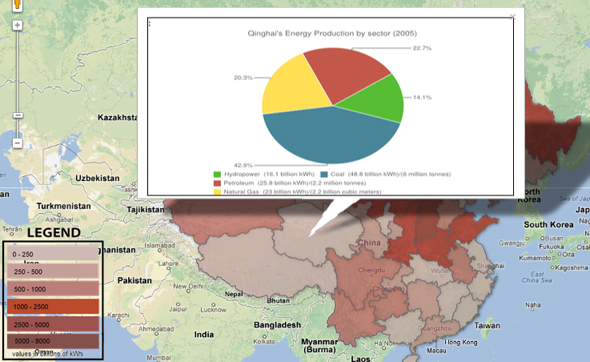

The El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) climate pattern is a coupled ocean-atmosphere phenomenon consisting of El Niño and La Niña cycles. This year is being classified as a moderate-to-strong La Niña, following 2009’s especially intense El Niño year. La Niña events double the likelihood of hurricanes and tropical storms for much of the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. According to the United Nations Environmental Programme, although ENSO is naturally occurring, a warming climate may contribute to an increase in frequency and intensity of El Niño cycles — which could mean more frequent cholera outbreaks, even in unexpected places like Haiti.

is a Traverse City-based assistant editor for Circle of Blue. She specializes in data visualization.

Interests: Latin America, Social Media, Science, Health, Indigenous Peoples

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!