Michigan Says It’s Ready For Next Drilling Boom

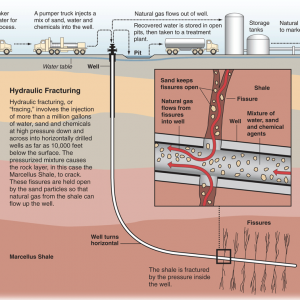

“Fracking,” which involves injecting water and chemicals to rupture deep shale and release natural gas, has raised public concerns about water supply, use, and contamination.

By Steve Kellman

Circle of Blue

A new natural gas exploration and production boom in Michigan could be opening in the wake of a surprisingly prodigious gas well in one central Michigan county that touched off a record-setting state lease sale.

Is Michigan ready to oversee production in the deep Collingwood Shale, and safeguard the state’s land and freshwater resources? One state official says yes. But a former state regulator and respected environmental consultant is more cautious.

Tom Wellman, manager of the mineral and land management division of Michigan’s Department of Natural Resources and Environment (DNRE), is a veteran of hydrocarbon development and regulation. He helped oversee the last great Michigan natural gas boom in the late 1980s and through the 1990s in the Antrim Shale—now the nation’s 13th largest source of natural gas.

Wellman told Circle of Blue that Michigan has a good record of managing oil and gas development and protecting its natural resources.

“Michigan has very strong casing and sealing standards which have been successful in protecting fresh water resources,” Wellman said. Casing and sealing involves inserting a large-diameter pipe into the well hole and cementing it in place to seal the well off from freshwater aquifers.

“The use of hydraulic fracturing to complete gas and oil wells is not in any way a new technique,” Wellman added. “It has been used in thousands of wells in Michigan and across the U.S. over the past 20 or more years. In Michigan it has a very safe track record.”

A Problem With The Frack?

But environmental consultant Chris Grobbel, a former environmental quality analyst with the state Department of Natural Resources, is not so sure. Grobbel has witnessed the state’s oil and gas industry from all sides, both as a state water quality specialist and while working for companies conducting cleanups.

When it comes to the Antrim and Collingwood formations, “I’m not comfortable in saying we’re comparing apples to apples,” Grobbel said. He noted that the Collingwood formation is far deeper than the Antrim Shale, and that vast amounts of water and chemicals are used to separate the natural gas from the rock.

“The chemicals being used vary from company to company and they’re proprietary,” Grobbel said. “There are as many as 900 out there that we know of and some 600 chemicals are allegedly in each of these products. It’s a soup, and there’s a lot of variations between companies in their own mixtures and they don’t have to disclose what they’re using so they don’t.”

A New Hydrocarbon Production Era in Michigan

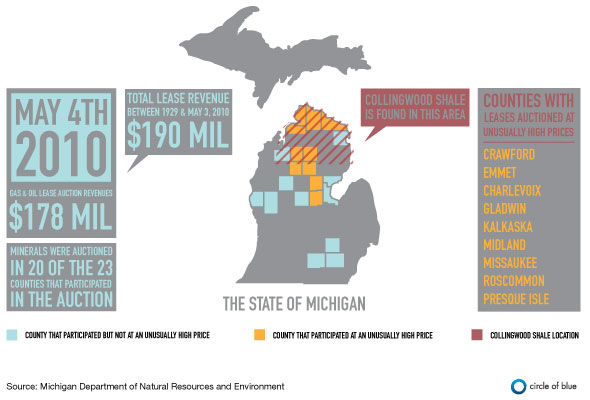

Until last May, when natural gas companies spent a record $178 million to snap up state mineral leases in 20 counties, hardly anybody outside the oil and gas industry had ever heard of the Collingwood Shale.

They do now. A subsidiary of the Encana Corporation, Canada’s largest natural gas producer, drilled a deep well in Missaukee County that produced an average of 2.5 million cubic feet of natural gas a day for 30 days. At current prices, that’s $12,500 worth of gas a day, or $375,000 a month from one well.

Over the past two years, Encana has bought up the mineral rights to 250,000 acres of land across the state. Other companies are doing the same. A new state mineral lease auction is scheduled for October and could encompass 500,000 acres.

Along with the land grab has come heightened concern over the effects the development could have on Michigan’s environment, including its lakes, streams and groundwater. Other states, among them Pennsylvania and New York, are taking a harder look at natural gas production practices following heated public hearings and complaints that drilling technique known as hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” is leading to contaminated drinking water and aquifers.

In Michigan, the new play is focused on the Collingwood Shale—a 40-foot-thick vein of rock nearly two miles beneath the surface. Like similar shale formations underlying other states, the Collingwood formation appears to be a rich source of natural gas, which burns much more cleanly than coal or oil.

The downside consequence of deep shale production is “fracking,” the use of millions of gallons of water mixed with thousands of pounds of chemical that is pumped under high pressure into the well to fracture the rock and free the gas from the fissures and pockets where it’s trapped.

The first well in Missaukee used 5.5 million gallons of liquid, according to the developers. While most of the fracking fluid is water, it also includes several other additives—a lubricant like glycol, a sand-like material to keep the fractured rock open, anti-foaming agents and biocides to suppress bacteria growth.

Just as potentially toxic as the fracking fluid itself are the other long-buried materials that they bring back to the surface, he added. Some 20 to 30 percent of that fracking fluid is pumped back to the surface.

“The fluid chemistry and toxicity is really driven by the naturally occurring chemicals that are coming up at toxic levels with the return flow,” he said. “It brings with it dissolved hydrocarbons—benzene, thylene, ethylbenzene, xylene isomers being the four that are typically focused on. It brings up heavy metals, it can bring up radionucleutides including radium 226 and other naturally occurring materials that are at toxic levels at the surface. And of course you’ve got all the additives.”

The drilling equipment and the wells also effect air quality, as the material returning to the surface can include carbon monoxide, methane and other gases, Grobbel said.

“That means greenhouse gases, acid rain-causing gases and asthma-causing particulates are all associated with fracking,” he said.

How Big Will Michigan’s Play Be? While the potential of the Collingwood Shale is still undetermined, Wellman said the formation underlies an area similar in size to the Antrim Shale formation—almost 10 counties across Michigan’s northern Lower Peninsula.

But the expense of drilling the Collingwood formation will produce much lower numbers of wells than the Antrim play, which produced nearly 10,000 producing wells, Wellman said.

“The (Encana) discovery well was almost 10,000 feet deep compared to Antrim wells in the 1,000-2,500 foot range,” he said. “As a result the Collingwood wells are many times more expensive to drill, would theoretically drain a larger area, and as a result would have much fewer wells drilled in a given area.”

He said one well would typically be drilled every 640 acres or one square mile rather than the one well per 80 acres that was drilled for the Antrim formation.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is conducting a $1.9 million study of fracking and is hosting a series of listening sessions around the country to take public comment.

A July 22 EPA session in southwestern Pennsylvania drew over 1,000 attendees, many who came to complain that fracking fluid from nearby wells had contaminated their drinking water, as well as area ponds and streams. Pennsylvania is experiencing a natural gas drilling boom in the Marcellus Shale that stretches across the state and into Ohio, New York, and West Virginia.

The EPA estimates that natural gas from shale formations like the Marcellus and Collingwood will produce more than 20 percent of the nation’s natural gas supply by 2020.

Steve Kellman reports for Circle of Blue from his base in Traverse City, Michigan. Photos by Heather Rousseau, a reporter and photojournalist for Circle of Blue. Graphics by Kalin Wood with contribution from Aubrey Ann Parker. Reach them at circleofblue.org/contact.

Read More: Encana establishes significant new land position on

promising Michigan Basin natural gas shale play (PDF), EPA Hydraulic Fracturing Research Study Fact Sheet (PDF), State Oil and Gas Lease Auction Sets Historic Record for Revenue

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!