Q&A: Thomas Bjelkeman-Pettersson Connecting Aid and Water Online at Akvo.org

Bjelkeman-Pettersson talked to Circle of Blue during the Tällberg Rework the World Conference in Sweden about sharing information to change the global direction on water and sanitation issues.

Welcome to Circle of Blue Radio’s Series, 5 in 15, where we’re asking global thought leaders 5 questions in 15 minutes, more or less. These are experts working in journalism, science, communication design and water. I’m J. Carl Ganter. Today’s program is underwritten by Traverse Internet Law, tech savvy lawyers, representing internet and technology companies.

Akvo.org uses cell phones and other technology to help people get the help they need, including that new rubber o-ring, and bring a level of accountability to distant projects. They put a phone number on a water pipe or pump, and you text for help. I spoke with Thomas recently at the Tällberg Rework the World Conference in Sweden.

Thomas, we’re at the Rework the World Conference and talking about all sorts of new ways of changing the world, resetting the world, changing our direction, coordinating and collaborating. It seems like Akvo is part of that whole mix, that whole calculation—tell me what Akvo does.

If there is a village level pump or something, and there is an issue and they don’t know how to solve that stick the phone number on the pump and say, this is where you get help if you need it. Of course you need the infrastructure to help deal with that. Who’s going to react? Who’s going to do something? The possibilities are absolutely there.

We don’t react until there’s a crisis, then we slowly get moving.

We don’t react until there’s a crisis, then we slowly get moving. It’s a difficult thing to get there, but in the end we tend to do what needs to be done. That’s how I look at it, but that doesn’t mean you can sort of sit back and relax and say, ‘well, somebody else will do it,’ because actually the issues are so big in front of us that everybody needs to participate.

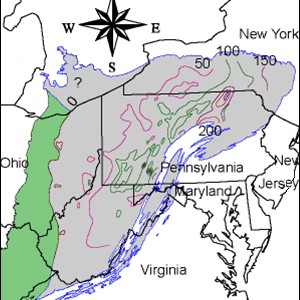

There’s just a ton of more work to do. The risk is that people are focusing so much on climate change that they forget that the biggest impact possible on climate change is actually the way we have water behaving in the environment… the hydrological cycle’s changes.

I spoke with Thomas Bjelkeman-Pettersson at the Tällberg Rework the World Conference in Sweden. He’s a co-founder of Akvo.org, an online platform for connecting people that work in development aid, particularly water. To find more articles and broadcasts on water, design, policy, and related issues, be sure to tune in to Circle of Blue online at 99.198.125.162/~circl731.

Our theme is composed by Nadev Kahn, and Circle of Blue Radio is underwritten by Traverse Legal, PLC, internet attorneys specializing in trademark infringement litigation, copyright infringement litigation, patent litigation and patent prosecution. Join us again for Circle of Blue Radio’s 5 in 15. I’m J. Carl Ganter.

Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!