Remedies for Nitrate-Contaminated Water in California are Anything but Quick, Cheap

Wells that serve more than two million Californians are contaminated with nitrates at levels that surpass public health standards, California Watch reports. In small towns and rural settings, schools and families often don’t have access to groundwater filtration systems. Tap water spiked with high nitrate levels can lead to illness in infants and some studies have found connections to certain cancers in lab animals.

By Julia Scott

California Watch, Special to Circle of Blue

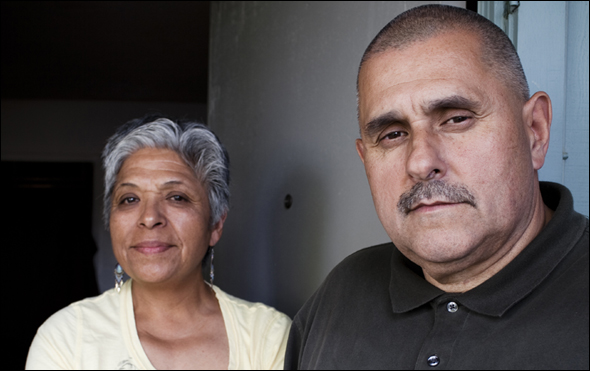

John and Rosenda Mataka never gave a thought to their tap water until 1995, when the city of Modesto took over the town of Grayson’s water supply wells and informed everyone that they had been drinking nitrate-contaminated water for over a decade.

Modesto officials began conducting regular tests of Grayson’s two production wells. The state Department of Public Health reacted to the results by requiring the city to install a treatment plant to rid the water of dangerous nitrate levels.

“I was angry. We just weren’t told. Every year they said the water was fine,” said Rosenda Mataka, who raised her son Emiliano on compromised tap water.

Although Emiliano and his parents show no indication that their health has been harmed by the water they drank for years, the Matakas worry about the long-term health impacts of exposure to tainted drinking water. Tap water spiked with high nitrate levels can lead to “blue baby syndrome,” which cuts off an infant’s oxygen supply. Some studies have found connections to certain cancers in lab animals.

Grayson’s water treatment system provides an oddly incongruous sight: an assortment of gleaming pipes and tanks that tower above apricot orchards and alfalfa fields, with a tall fence wrapped around them and a big warning sign that says “Caution: Chlorine.”

It’s Grayson’s accidental landmark, a symbol of the hidden legacy that has prevented this rural outpost of 1,200 from becoming the prosperous Modesto suburb it could have been.

In a way, Grayson is lucky. Most small communities of its size with serious nitrate problems can’t afford expensive water treatment plants. That means these communities, made up largely of low-income families who work the fields, end up drinking whatever comes out of the tap, even if the water violates public health standards for nitrates.

At least one million Californians rely on private wells that have no public health oversight. These residents are at high risk for nitrate contamination because their wells are shallower than municipal wells. Nitrates are colorless and odorless, making them hard to detect without lab testing.

At the other end of the spectrum, cities in Southern California have spent millions of dollars on nitrate treatment plants because they have no other choice – dirty or not, the groundwater is crucial to meet population growth while access to imported water shrinks. The Irvine Ranch Water District, for instance, built a $33 million system to remove nitrates in 2007. It costs an additional $2.3 million a year just to operate and maintain. The plant itself serves 50,000 water customers in Orange County.

Other California communities will be facing the same tough choices in the coming years. California’s population is projected to increase 53 percent by 2050. Of the 50 million people who will one day call this state home, many will settle in the greater Los Angeles area, Inland Empire, and parts of the Central Valley – areas that overlie some of the most nitrate-contaminated groundwater in the state.

City planners are looking to groundwater to supply one-third of the water needed to accommodate California’s coming population boom, or 1.1 trillion gallons per year – more than any other source, according to the Public Policy Institute of California.

Looking around Grayson today, it’s hard to believe the town was once in the running to become a major suburb of Modesto. Twenty years ago, a developer was planning to build a 633-unit subdivision at the site of a peach orchard in Grayson.

Those dreams were dashed shortly after Modesto installed a de-nitrification plant. Although it can barely afford it, the city spends $800 per acre-foot of water to make water drinkable for Grayson’s 1,200 residents – up to $19,440 a month, four times the cost of the treated Tuolomne River water Modesto pipes to half its 210,000 residents.

Another problem is the leftovers: Grayson’s ion exchange process leaves behind hundreds of tons of saline brine that can’t be recycled or reused, so Modesto pays extra to export four truckloads of it each week to a Bay Area wastewater plant. At those prices, the city quickly concluded it couldn’t afford any new water connections in Grayson and banned them outright. The ban is still in place today, minimizing the area’s population growth.

“If water wasn’t a problem here, the whole area would be developed in a heartbeat,” said John Mataka, who works for Stanislaus County as a behavioral health specialist. He and Rosenda both advocate for environmental justice issues with a variety of local and state organizations.

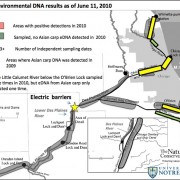

Experts say the slow spread of nitrates underground has already affected millions of Californians, mostly due to a legacy of leaky septic tanks and intensive nitrogen fertilizer-based farming over the last 60 years. Nitrates are the leading cause of well closures in California. Scientists say that if nitrate concentrations don’t taper off, the pollution will eventually sink deep enough to affect the well water that millions of Californians depend upon.

Studies have shown that although only 3.5 percent of public water supply wells in the Central Valley exceed the public health limit for nitrates today, an additional 13 percent of wells are at substantial risk of contamination.

That message is somehow getting lost on people, says Karen Burow, a Sacramento-based scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey. Past farming practices have already contributed to tomorrow’s nitrate problems, and today’s contributions are making the problem worse.

“I think that’s the most important point we can get across – that there is a lot of nitrate in shallow groundwater and it’s moving, and we don’t see it going away very fast. There is some urgency for the policy people to figure out what to do,” Burow said.

Solving the groundwater problem will take imagination – and a lot more money than the state is spending. California voters have passed two water bonds since 2002, worth more than $8 billion. Roughly $2 billion was allocated for clean, safe drinking water.

No estimate exists for what it would cost to clean up the nitrates in our groundwater basins, in part because the state has limited knowledge about where the pollutants are and where they go when they reach the water table.

The Environmental Protection Agency has estimated that the cost of treating all the polluted groundwater in California over the next 20 years, including nitrates, would amount to $7.5 billion.

Tackling the source

-Ken Landau

Activists and regulators agree that the best way to solve the nitrate problem is to prevent it. But that is easier said than done. State regulators have started requiring certain operations to limit the nitrogen they apply to land. Records show, however, that in many cases, officials have been aware of ongoing nitrate pollution for years – and took little action to address it.

One of the best examples of this is the state’s dairies, which grow crops with manure. Many dairies lack enough cropland to absorb all the nitrogen they produce. As a result, they over-apply liquid manure, causing nitrate problems.

Most dairies began testing their domestic wells for nitrates in 2007 and 65 percent of the dairy wells exceeded the public health limit for nitrates. Forty-two percent of wells had nitrate levels that were twice the drinking water standard.

Many dairies moved north, to the Central Valley, after Chino water regulators passed strict rules limiting the number of cows.

Since 2000, the state has mandated that 48 dairies submit groundwater test results – in response to numerous other findings of nitrate contamination on their land. Yet none of the dairies were fined, required to cease operations or asked to clean up a nitrate problem identified by the state.

Dairies receive violation letters for not monitoring properly, but exceeding the nitrate limits rarely has serious consequences.

Records show some dairies were even suspected of spreading contamination to adjacent lands, potentially affecting the drinking water of neighbors and farmhands living onsite. But only one dairy, The Bosma Milk Co. in Tipton, received a violation letter specifically for high nitrates in groundwater beneath the property, according to an online database of state enforcement actions.

The Bosma Milk Co. has reported nitrate concentrations above the public health limit since 2003. Like many other Central Valley dairies with nitrate problems, nitrate concentrations in some of Bosma’s wells spiked as high as five times the pollution limit between 2000 and 2007.

The dairy received a violation letter in 2008, but no fine. The Central Valley Regional Water Board has asked the dairy to collect more information before it takes action.

Gary Bosma, co-owner of Bosma Milk Co., said he and his brother Jake have gone out of their way to comply with water quality requirements imposed by the state. He suggested that regulators would have a hard time proving that nitrates were coming from Bosma given that there are other dairies in the area.

“We have neighbors and the water moves around in the aquifer. Just because one well pops up positive doesn’t mean it’s coming from that dairy,” Bosma said.

Officials say they have been aware of nitrate issues at dairies for a long time.

“The solution isn’t usually to just shut down a dairy. The ones that we found having problems, we’ve worked with them to get more land, improve their cropping practices, in some cases line manure basins,” said Ken Landau, assistant executive officer of the Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board.

In 2007, Central Valley regulators started requiring most dairies to develop plans to manage their manure to reduce water contamination. Another rule, the first of its kind in the country, required dairies to sample their domestic wells for nitrates. If the levels are too high, the dairy needs to pay to install additional monitoring wells to gauge the extent of the contamination.

The program was welcomed by environmentalists, but Dairy CARES, a statewide dairy-industry coalition, feels the requirements are too burdensome. The group is working on an alternative that calls for installing wells in select regional locations to monitor contamination, an approach that would avoid pointing fingers at individual dairy operators.

“It’s a much broader scale than holding an individual responsible for their exact actions,” said Darrin Polhemus, deputy director of the State Water Resources Control Board’s division of water quality. “Obviously that’s what we’ll want to get to eventually, but that’s not the focus. It’s not designed to find that one guy out there.”

An expensive problem

It’s too late to prevent nitrate contamination in many Southern California groundwater basins, especially in heavily urbanized portions of Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties.

It’s a problem that harkens back to the region’s agricultural legacy. Land now covered with suburban neighborhoods once sprouted with citrus trees and vegetable fields where farmers used nitrogen fertilizer. Until recently, the Chino Basin was home to more dairies than anywhere in the world.

Nitrate problems were detected as early as the 1970s in the Chino Basin, one of the largest groundwater basins in the state. The area is at the heart of California’s Inland Empire and home to more than a million people. Nitrate concentrations in the worst-hit parts of the basin were double the EPA threshold in the 1980s and quadruple the limit by 2000, according to records.

Regulators with the Santa Ana Regional Water Quality Control Board tried with limited success to contain the problem by banning dairies from applying manure to land in the Chino Basin in 1999.

Today, residents pay high water bills to bankroll multimillion-dollar nitrate treatment plants in places like Pomona and Riverside. The Inland Empire Utilities Agency in western San Bernardino County is in the midst of a $300 million project to expand its nitrate removal plant as part of an aggressive strategy to cope with drought-related limits on imported water.

“We recognized that imported water was vulnerable and less reliable,” agency General Manager Rich Atwater said. “We’ve literally hit the wall with the Delta. We’re in a huge economic recession and everybody recognizes that we’re going to go from 38 million to 50 million people in the next 25 years, and Southern California is a big part of the demand.”

Times have changed since the 1970s, when water managers could just shut down a well and dig a new one if nitrates became a serious problem. Atwater says the causes of nitrate contamination were ignored for too long, creating a problem for everyone in the region.

“All that nitrate contamination that we’re addressing today is literally a legacy of 50 to 100 years ago,” Atwater said. “Prevention is so much more cost effective – 10, 20 times as much. It’s so much more expensive to remove the contaminant from the groundwater basin than to keep it from getting there in the first place.”

In Modesto, the city has had to shut down 10 of its 140 municipal wells because of nitrate contamination in the past 15 years, and there will likely be more, said Allen Lagarbo, deputy public works director.

“All cities on wells in this area start developing contamination problems eventually,” he said.

-Jean Moran

The combined population of cities in the Sacramento Metro region and the San Joaquin Valley is projected to top 9 million by 2030. The population in the Central Valley has doubled every 30 years since 1900 as residents move onto former farmlands.

Meeting those future water demands is not as simple as building a new generation of nitrate treatment plants, as Modesto has discovered. The most common technologies to remove nitrates, ionic exchange and reverse osmosis, can be expensive and cumbersome.

“We do this crazy thing now and take pristine, beautiful water and put it on our farms, and the minute it soaks into the ground it’s filled with nitrate, and then we ask cities to clean up marginal water and use it as drinking water,” said Jean Moran, professor of earth and environmental science at CSU East Bay and a former groundwater research scientist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

A Sacramento solution?

In the Central Valley, farmers may soon face regulations on their use offertilizer similar to an order imposed on dairies in 2007. The agricultural industry wants those rules to remain voluntary and says it would be unfair for regulators to require farmers to comply with strict statewide water quality standards.

Nitrogen fertilizer use in California has stabilized at an average 700,000 tons each year, but it’s unclear whether voluntary strategies have made a difference for nitrate levels so far. It took 50 years to detect nitrate problems in many areas and it will take decades to see changes, experts say.

One option would be to require farmers to limit the amount of fertilizer they apply to their fields. That would require new legislation. The State Water Resources Control Board does not have the authority to impose those limits.

Lawmakers have directed hundreds of thousands of dollars of aid to small communities struggling with nitrates, and established demonstration projects for good farming practices through the University of California. But when it comes to tackling fertilizer itself, results have been mixed.

Former Bay Area state Assemblyman Johan Klehs tried to pass a bill in 2006 that would have raised the mill tax on fertilizer. The money would have been used to provide grants to communities affected by nitrate contamination. (In California, fertilizer is exempt from local and state sales taxes). The bill died in the Assembly’s Agriculture Committee.

“All efforts along those lines automatically go to the ag committee and they die there. Legislators are not friendly to anything that could negatively impact agriculture,” said Debbie Davis, legislative analyst with the Oakland-based Environmental Justice Coalition for Water.

State Senate Majority Leader Dean Florez, D-Shafter, calls nitrates “a backwater issue in Sacramento.”

“These are the kinds of things public policy makers need to hear,” he said. “It’s always difficult to get any of these things on the radar screen. … We’ve got to get our farmers to recognize the long-term impact of these materials on water systems. People say it’s the end of a major, multi-billion dollar industry without these fertilizers.”

Scientists with the U.S. Geological Survey have calculated that even if fertilizer inputs ceased immediately and forever, nitrate levels would continue to climb for many more decades before starting to decline because of the lag time in deeper aquifers.

All the more reason to take preventative action, says Eli Moore, a research associate with the Oakland-based Pacific Institute.

“We can deal with nitrate contamination once it’s already reached the tap water, or we can try to prevent nitrate contamination before it becomes a problem,” Moore said. “It’s really a question of whether we as Californians are going to ensure that all Californians have access to clean drinking water.”

Grayson’s moratorium on new water connections hasn’t kept people from building new homes and simply digging their own backyard wells at the risk of exposing themselves to dangerous levels of nitrates.

Nitrate concentrations in Grayson’s raw water have tested as high as 65 milligrams per liter over the past 15 years. The public health limit is 45 milligrams per liter. One milligram is equivalent to half a teaspoon in a swimming pool. It may not seem like much, but for vulnerable populations, like infants, the effects can be acute, experts say.

“If this is an issue now, can you imagine a town three times the size?” asked John Mataka. “It would have been a calamity.”

This story was produced in collaboration with KQED Central Valley Bureau Chief Sasha Khokha and Christopher Beaver of CB Films. It was edited by Mark Katches. It was copy edited by William Cooley. For the whole story, plus interactive tools, film clips, a photo slideshow and links to a three-part series on nitrates produced by KQED Radio, visit California Watch. Read more of California Watch’s work on Circle of Blue.

Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

All biological life consist mostly out of four elements (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen), which by themselves are as old as the universe and only part of such life for a few weeks. Biological life therefore is a continuous recycling of these elements and in order to understand what is happening in the biosphere it is essential to understand the lifecycles of these elements. When one deals with human impact on the biosphere, it is essential to evaluate how these cycles are impacted by such behavior.

Focusing on one specific impact, in this case nitrates, again diverts the attention of the public and gives them a reason to point the finger of blame and in this case again at farmers.

Nitrates are in synthetic fertilizer used to grow crops and their excessive use is causing it to get into groundwater, but it also becomes organic matter and when consumed ends up in the urine of animals. As urea it is either directly used as a fertilizer to grow new organic matter or results first as ammonia which later is oxidized into nitrates and again in all these forms used as fertilizer.

When dissolved in water in a molecular form, it will travel wherever the water will go even in rain, as green rain.

The nitrogen life cycles (unlike the carbon, hydrogen and oxygen life cycles) are complex and the main reason they are mostly ignored. A prime example is that nitrogenous (urine and protein) waste in sewage from cities is still not required to be treated, while it besides exerting a direct oxygen demand (just like fecal waste) also is a fertilizer for algae and causes eutrophication, resulting in dead zones. If required to be treated, which is economically possible, probably none of the 300 ton of fertilizer entering daily in the Gulf of Mexico would be eliminated.

The reason that nitrogenous waste in sewage is ignored is caused by a faulty applied water pollution test and while EPA of the record in 1987 admitted that this test and regulations should be corrected, EPA also claimed that this was not possible as it would require a re-education and re-tooling of an entire industry. (www.petermaier.net)

Sadly nobody is willing to hold the EPA accountable