Small Solution to Large-scale Water Pollution — Protozoa Detect Contaminants

A technology start-up is looking small to solve a big global problem.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

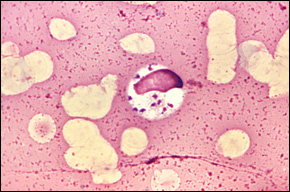

A Massachusetts-based company Petrel Biosensors is using single-celled organisms called protozoans to do what test tube-toting researchers have not been able to do—test water quality cheaply and accurately in real time.

Called the Swimming Behavioral Spectrophotometer (SBS), the system detects toxins in water by analyzing how the protozoa move throughout the sample. Most toxins are known to disrupt calcium transport. Since the hair-like cilia responsible for protozoan motion are sensitive to aqueous calcium content, the presence of toxins can cause an erratic and irregular response in the microorganism.

Although some protozoan species are known to cause water-borne diseases such as malaria, dysentery, and giardia, other types of this microorganism are central to the technology designed by Scott Gallager, a scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, an ecological research center. The system uses up to three types of protozoa per project, since some are better suited for fresh water and others for brackish water.

In an interview with Circle of Blue, Petrel’s chief executive, Robert Curtis, said that a particularly timely use would be for gas field operators to test the quality of the water produced by hydraulic fracturing, a drilling method that uses a high-velocity mixture of water and chemicals to crack underground rock layers that contain natural gas.

“With a real-time test, you can have a good idea of the clean-up needed immediately,” Curtis told Circle of Blue.

Other applications for the system include water monitoring for public drinking water supply, for military units in the field, and for industrial waste discharge.

Because of the multitude of uses, the SBS was recently named a ‘Better World’ technology in the 2010 edition of the Better World Report, a publication from the Association of University Technology Managers, a professional group.

The recognition comes despite a low profile for the SBS. Curtis said the technology has flown under the radar because Gallager, the inventor, was working on too many other projects to publish the data.

Gallager, who was not available for an interview, and his former colleague Wade McGillis—now with Columbia University—developed the technology while doing research on how climate change would affect plankton colonies.

The result of Gallager’s work, which was funded by a $1 million Department of Defense grant, is a water-testing system that is cheaper and faster than any that is now available. The on-the-ground SBS provides instant feedback at $1 to $2 per test, Curtis said, while other systems that include laboratory analysis range from $50 to $250 per evaluation.

The SBS prototype, which is licensed for commercial development by Petrel, is roughly the size of a micro-refrigerator popular in dorm rooms. Curtis said he envisions future iterations will come in stationary versions for monitoring a river or drinking water system and handheld units for field-level work.

If the SBS can be scaled up, it would fill a significant gap in the global health matrix.

The Joint Monitoring Program—the United Nations body in charge of assessing progress toward the Millennium Development Goals for water and sanitation—says water quality is an ‘elusive indicator,’ meaning that water quality measurements are rarely carried out because the process is so expensive, time-consuming, and logistically challenging.

Instead, the focus for drinking water development money has been infrastructure—getting water to the people.

Whether the water being distributed is safe to drink has been assumed rather than assessed. The JMP began to address this imbalance several years ago with a rapid-assessment pilot project that tested water quality in eight countries, the results of which were published earlier this year.

Nearly 90 percent of piped water sources met World Health Organization standards, but only 40 percent to 70 percent of other improved sources—such as public taps and protected wells—did so.

Curtis said that he plans to speak with the WHO, the Gates Foundation, and other major donors in the global health field, but first he needs to “put more meat on the bones” of the SBS.

With the recession trailing a long wake, Curtis said funding the project has been the biggest challenge for Petrel. The company needs at least $2 million to move the SBS forward.

Brett Walton is a Seattle-based reporter for Circle of Blue. Contact Brett Walton

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Good website about pollution n good idea to talk n pollution is most importing thing for our environment n that is not our future to living in the pollution world,so guy’s stop wasting the water n keep saving water n other thing …