Taking the Pulse of Global Freshwater Issues

What’s happening and what will happen in the water world in 2010. A look ahead as citizens, companies and nonprofits jockey for position.

By Andrew Maddocks

Circle of Blue

March 22, 2010 marks World Water Day, a 24-hour observance held annually since 1993 to draw attention to the role that fresh water plays in the world. In recent years it has focused global concern on the dwindling supply of clean water.

With governments from Australia to India feeling the heat of dryness like never before, multinational corporations pledging to become better global water citizens, and a multitude of nonprofit organizations gaining position in the councils of influence worldwide, the global freshwater crisis is steadily becoming a top public priority.

In January, global business and elected leaders assembled in Davos at the World Economic Forum learned one more striking fact that underlies international concern. By 2030, WEF experts said, people will withdraw 30 percent more water than nature can replenish. Unless practices for using and conserving water shift dramatically, shortages will hit communities and businesses, especially agriculture, which uses 70 percent of the world’s fresh water.

Here is some of what we expect in a busy year in the world of water:

Contents

- Awareness and action

- Business of water

- Water and Global Health

Awareness and Action

A team of researchers and advocates that includes the Global Water Partnership, Global Public Policy Network on Water Management, Stockholm International Water Institute and the Stakeholder Forum, have been working with hundreds of smaller groups to rally support for water’s role in international climate change negotiations this year.

The work was prompted by the disappointing outcome of the United Nations Climate Change Conference in December, when water was left out of the Copenhagen Accord. The non-binding agreement calls for modest action on global warming.

If the international climate treaty doesn’t better emphasize the water-climate intersection, people living in vulnerable coastal nations, such as the island of Maldives, and farmers facing volatile rainfall, such as those in Australia, will be unprepared to face major catastrophes, Stakeholder Forum Policy Coordinator Hannah Stoddart told Circle of Blue.

At the international level, Stoddart and her team work directly with UN officials, and also are coordinating an unofficial international water day in Bonn, Germany in June. They are arranging high-level round table discussions that will rally more support for water issues in the months leading up to the next climate change summit in December, in Mexico.

“The eventual goal is for a recognition on an international level that there are currently no operational international treaties addressing water issues specifically,” Stoddart said. “We’re at the beginning of quite a long journey.”

Garnering local support is an important component of making sure the issue gains global prominence, according to marketing experts who work on environmental issues.

“It’s so hard to make people realize that they have a connection to the issue, to the sources of the problem,” said Joel Finkelstein a senior vice president and head of the environment team for Fenton Communications, a U.S.-based firm.

Water offers an even bigger challenge in some ways, he added. It’s still extremely difficult to illustrate the consequences of our current water consumption in countries like the U.S., where citizens can turn on the tap without thinking twice.

But the consequences of water scarcity are more powerfully conveyed through emotional stories than statistical reports. And Finkelstein believes that social media promises new ways to humanize water and environmental issues.

“Geography’s going to mean a different thing,” Finkelstein said. “It’s really important to tell local [water] stories with local impacts.”

Business of Water

A drop in industry sales and the greening plans of Olympics host cities like Vancouver and London indicates that the battle between bottled water and tap water may be on the verge of greater international attention.

The battle is the subject of the upcoming book, “Bottled and Sold: The Story Behind Our Obsession with Bottled Water,” by Pacific Institute President and Circle of Blue contributor Peter Gleick. Grassroots efforts like Food & Water Watch’s Take Back the Tap campaign, and a trans-Pacific voyage in a boat built entirely from plastic beverage bottles, raised awareness.

Water has become one of the highest earning commercial products of the last 100 years, earning tens of billions of dollars in annual sales, according to the publisher’s Web site. Millions of plastic bottles are thrown away almost as quickly as they’re produced each year; 86 percent are not recycled.

According to the consumer rights group Food & Water Watch, plastic bottle production requires 17.6 million barrels of oil and 2.7 million tons of plastic annually. Incinerating the bottles releases toxic byproducts.

Gleick’s columns and Pacific Institute reports have consistently addressed the environmental, cultural and cost concerns of a bottled water lifestyle. In a recent column, Gleick highlighted consumer revolts curbing the rise of bottled water sales. A Worldwatch Institute report released in late February found that the growth rate of bottled water consumption in 2008, while still positive, had dropped.

GE: One company’s approach, inside and out

Many of the world’s largest companies face a tug of war over water use internally and within their communities. This trend will expand, predicts Jeff Fulgham, chief marketing officer at General Electric. GE, a company that earned $30 billion last year and whose business units run the gamut from coal-fired electricity turbines to a water infrastructure division, is looking at water efficiency system-wide.

In the past few years the world — and many of its largest companies — has reached a tipping point over water, Fulgham said.

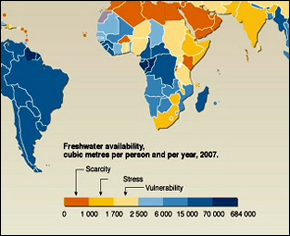

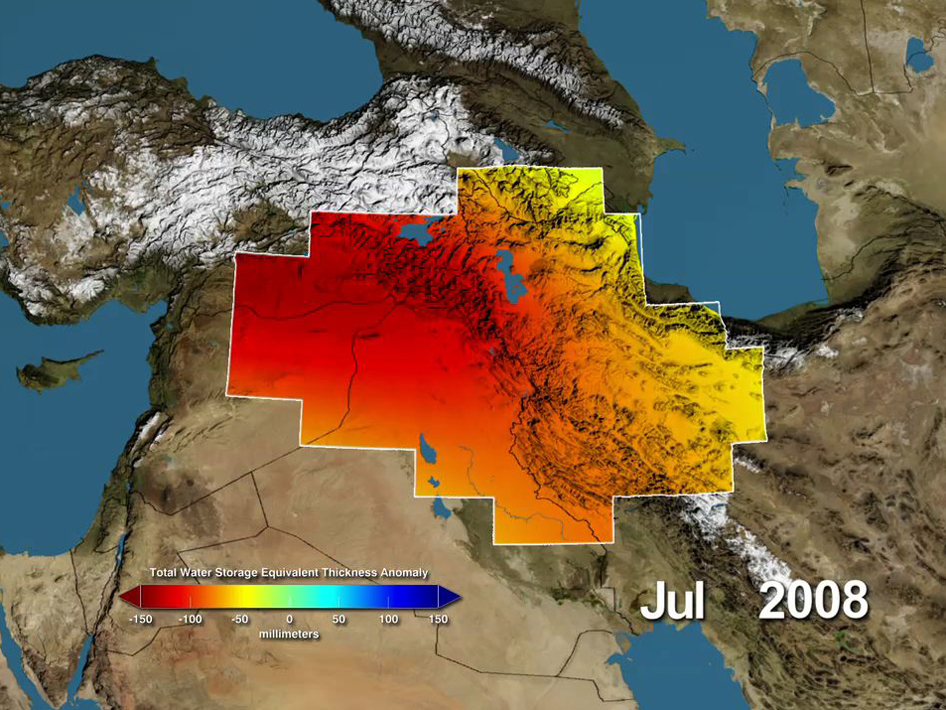

Global demand is exceeding supply. That imbalance is greater in some parts of the world than others.

The numbers are numbing — at 4,500 billion cubic meters, global demand for water already exceeds supply. By 2030 demand for water will grow to 6,900 billion cubic meters, leaving 40 percent supply gaps in some areas, according to a 2009 McKinsey report.

GE, only one of the companies aggressively assessing future water supply risks, addresses this gap in its internal water use and interactions with a spectrum of clients that need home appliances, jet engines or nuclear power plants. The company aims to reduce its water use by 25 percent by 2015.

As GE tries to reduce its overall water consumption, two other key issues further define the company’s approach to water management — quality and pricing.

“It’s the same basic factors we were looking at four years ago, but on steroids,” Fulgham said. Some industries are using poor-quality water, while others are facing more stringent regulations, especially on the discharge side, he added.

“They’re pinched in the middle,” Fulgham said.

At the same time some companies and consumers aren’t paying enough for their water, Fulgham said, to reflect how scarce the resource is.

“Customers aren’t feeling a cost for water, so it’s tough to get them to spend any money to improve their situation,” he said.

Meanwhile weak government regulations have let water quality deteriorate in some places, such as Eastern Europe and the developing world. Multiplying demand, deteriorating quality, and disconnected pricing are draining major water reserves.

Fulgham said GE is using a three-pronged approach to respond internally and through its customers: conservation, water re-use technologies and desalination.

Desalination, which until recently was cited by many as a panacea for supplying drinking water in dry nations, may be reaching the limits of practicality. It is energy intensive and expensive. Since newer technologies can’t guarantee success, GE is emphasizing conservation measures and clean, efficient water re-use.

GE, like other corporations, is upgrading its appliances, water re-use and treatment equipment. It’s also updating its manufacturing, energy, appliance and real estate holdings.

Fulgham said he’d like to tackle excessive water use in agriculture. Minimizing the flow of water through farms could intervene directly in what he calls the “vicious cycle” of water, reducing consumption and pollution at the same time. His company also cultivates talent in Ivy League and top engineering school programs related to water, the environment, and business.

Human rights related to water are a “huge deal,” Fulgham said. GE is working with its own foundation, global peers like the Gates and Tata Foundations, entrepreneurs and appropriate technologies for water-deprived areas to build sustainable programs in the neediest areas.

Read more from Circle of Blue’s conversation with Fulgham here.

The CDP Water Disclosure Project in 2010

| ——— February – March | Companies review and sign water disclosure questionnaire. |

| ——— April 1 | Questionnaire sent to approximately 300 of largest corporations in water-intensive sectors globally. |

| ——— July 31 | Deadline for companies to respond to questionnaire. |

| ——— October – December | Findings launched through CDP Water Disclosure. |

In a measure of global corporate attention on freshwater issues, 300 corporations in water intensive industries and high-risk areas have pledged to release detailed information about their water usage through the Carbon Disclosure Project. CDP is an independent British non-profit founded ten years ago to help organizations measure and disclose their greenhouse gas emissions. It also creates strategies to help deal with climate change. Now CDP is applying its emissions model to water.

The first stage of the new program starts April 1 when CDP will survey 300 member companies. The results, which CDP plans to release by the end of 2010, will give the companies and their investors new tools to analyze water-related risks and bottom line opportunities.

Marcus Norton, head of the water disclosure program, said the survey’s broad acceptance is a sign that companies are beginning to understand water is an important part of their supply chain.

“Companies will need to operate in a water-constrained world,” Norton said. “Investors will be very interested in knowing that it’s a part of their long-term planning.”

The questionnaire has three general categories: water management and governance, water-related risks, and metrics. The first group of questions asks how companies deal with various parties, from governments to local groups, connected to a water supply. Investors, Norton said, want to know companies are anticipating the dangers of operating in water-scarce regions.

Metrics is the most challenging category to survey because there’s no global standard for water measurement. Gathering exhaustive data could put an overwhelming burden on companies.

Norton said CDP designed the survey to collect meaningful data that doesn’t create an excessive reporting burden. While it’s a “rocky” process that will develop over many years, companies have no incentive to mislead shareholders, Norton said.

Useful data is harder to gather about water than greenhouse gases. Carbon emissions have the same affect on London as they do on Michigan. Water information is most valuable when localized down to the watershed level because conditions can be so variable.

“Until you look at that I don’t think the data is truly meaningful,” Norton said.

Norton will use the survey’s first year to explore ways the survey should expand. He wants to prioritize two additional categories: the largest, most water-intensive companies and the regions with the worst water scarcity.

“This is an iterative process of improvement,” Norton said. “We’ll be developing modules for different industries and sectors.”

Norton thinks this project will advance global awareness of the water crisis in the coming years.

“I’ve heard people describe us with water as where we were with carbon and climate change five years ago.”

United Nations CEO Water Mandate

Started by the United Nations in 2007, the voluntary CEO Water Mandate is designed as a public-private venture to help companies develop, implement and disclose water sustainability in their supply chains. In the long term, the CEO Water Mandate hopes its efforts will help mitigate the effects of the global water crisis.

Companies that sign the mandate pledge to analyze and reform six key water management areas:

* Direct operations

* Supply chain and watershed management

* Collective action

* Public policy

* Community engagement

* Transparency

Beverage industry giants PepsiCo, Coca-Cola and Nestlé have signed on, along with more than 50 others. The Pacific Institute, Circle of Blue’s parent organization, manages the program.

But not everyone supports the mandate. An active community is skeptical of corporate involvement.

Corporate Accountability International, a grassroots watchdog organization, calls the CEO Mandate — among other corporate initiatives — a public relations effort by for-profit corporations to gain control over the world’s water resources and services.

“Corporations like Coca-Cola, Suez and Nestlé are trying to turn water into a high-priced commodity, the oil of the 21st century,” said CAI in a statement. “This presents a grave threat to people’s access to water. The United Nations needs to stand up for public, democratic control of a resource that is essential to life.”

In addition, more than 125 organizations in 35 countries urged UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon to withdraw the UN’s support for the mandate. Tony Clarke of the Polaris Institute, a Canadian-based political think tank, noted during a side event to the World Economic Forum earlier this year that the CEO water mandate is a “thinly veiled public relations effort by for-profit corporations to gain greater control over water resources and services around the world.”

Pacific Institute Program Director Jason Morrison told Circle of Blue he objects strongly to the assertions.

“There’s a lot of evidence we’re shown that this is not a public relations exercise,” Morrison said. “In fact, I would challenge anyone to find an initiative, focusing on the private sector, that has done more in the last two years to define what corporate water stewardship means in practice than the UN CEO Water Mandate.”

The mandate has been unusually successful, Morrison said, in pushing companies to identify water-related impacts and risks throughout their operations. It also places a major emphasis on transparency of water-related data in companies.

Morrison pointed to a study called “Murky Waters? Corporate Reporting on Water Risk” by the Ceres investor coalition, Bloomberg and UBS Financial Services as an independent measure of success. The study ranked companies’ disclosure of water data across different sectors. While the mandate did not cover all the sectors, its companies ranked among the highest in the study.

The mandate also defends human rights and the democratic water regulatory process, Morrison said. The Pacific Institute helped draft a responsible engagement and public policy document for companies that’s undergoing a month-long public review. It pushes companies to consider a range of groups its water policy affects, and guides company relationships to serve their best interests.

While Morrison believes the mandate’s success in reforming the private sector is unparalleled and has ongoing potential, he pointed out that some groups would rather not deal with the private sector at all.

“There are others, myself included, that hold the view that because industry uses such a large amount of water, it would be to everyone’s benefit if they were better stewards of that water,” Morrison said.

It’s nearly impossible to get through a day — especially in America — without using an industrial, water-intensive product. Morrison sees that as a call to action and a validation of the mandate.

Water and Global Health

While companies assess risks and look for ways to conserve, scarce and polluted water supplies remain one of the world’s greatest public health challenges. More children die every day from a lack of clean water, sanitation and hygiene than from AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis combined, while 20 other potentially fatal diseases can be reduced if water access was better, according to the World Health Organization.

Such widespread fatal illness could severely limit the United Nations Millennium Development Goals, which form the pillars of the UN’s sustainable development program and are widely seen as benchmarks by which world progress or decline is measured.

A study by the Japan Water Forum in 2005 found that seven of eight U.N. goals heavily depend on access to clean water for success. According to the study, up to 50 percent of the success rate depends on access to clean water.

“We can’t accomplish these goals if people are sick repeatedly, or if women are out hauling water two to three hours every day,” said David Douglas, founder and executive director of Water Advocates, a Washington-based nonprofit group focused exclusively on raising funds and awareness for water-related health issues.

Douglas says he’s motivated by the staggering number of deaths tied directly to water, and the broader, indirect threats limited resource supplies pose to development.

Water Advocates, which will dissolve this year, is hoping for several pieces of its advocacy work to fall into place before it closes.

“Whatever the outcome of this year, we’ll have plenty of voices to keep going,” Douglas said.

The research, he says, offers no other interpretation: Water and sanitation-related diseases must be on par in global attention and funding with AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis. Right now they are barely mentioned in government spending negotiations, Douglas said, adding that he hopes the U.S. will allocate $500 million in 2011 to tackle water-related health problems in the developing world.

The immensely diverse global water challenges — health, business sustainability, climate impact, agriculture, gender equality, human rights, infrastructure development and repair, to name just a few — form a swarm of intersecting complexities that, says Douglas, will define the success or failure of development in the coming years.

Andrew Maddocks is a reporter for Circle of Blue working from the Traverse City, Michigan newsroom. Reach Maddocks at circleofblue.org/contact

is a Washington, D.C–based correspondent for Circle of Blue. He graduated from DePauw University as a Media Fellow with a B.A. in Conflict Studies. He co-writes The Stream, a daily summary of global water news.

Great story, Andrew. Where does waterbag technology fit into your thoughts related to the economics and politics of water? See YouTube and connect to “Spragg Bag” to see video, and the http://www.waterbag.com website for information. We hope to announce a demonstration of our waterbag technology in the next few months.

The issues around water are very critical and important. We see lots of water resources drying up daily. For instance in the olden days our ancestors use to have lots and lots of water, but today our water resources are gradually deteriorating. The argument may be that rain patterns are no longer similar, but the question is where have we gone wrong?

Starting with the hydrological cycle we have caused lots of disturbances to the normal cycle of water. Our activities are busy polluting our water resources and we are never ready to give our resources a chance to naturally assimilate themselves. Thou this does not sound good because we are all looking forward to our water to do more of the productions we want and we forget that the more we pollute it the more it will cost us in the future.

Getting back to how our ancestors lived and took a bit care of our resources. They use to move from place to place searching for water and food, and where they found ample they dwelt. Thus they gave more of the resources to recover, thou it is not 100% possible today; we need to at least minimize the negative impact we making to our water resources. If we let our resources to deteriorate we will left with nothing to hand-in to our future generation and the emerging wars will be more on water.

One more challenge is population growth, the more our population grows the more demand will be posed on water and our water resources may not be able to accommodate us at all. The world still has a lot of work to do on ensuring that our water resources do not end up causing us to kill each other. The question is how much love we have to our resources and how much value do we give to them. If we really value our resources we shall care and bring about strategies to alleviate the dangers in place.