At the Helm of the First U.S. Freshwater Studies Program — Meet Hans VanSumeren

Hans VanSumeren has performed extensive water-related research from Maine to the Florida Keys, as far West as the Hawaiian Islands, and all the way to the bitter north of the Alaskan Bering Glacier. His latest adventure — creating the only Freshwater Studies program in the nation — is innovatively using education to combat the global water crisis.

By Aubrey Parker

Circle of Blue

In 2008, Hans VanSumeren, a water researcher and one of the most highly regarded underwater vehicle pilots in the nation, made one of those big career decisions that fits an adventurous professional ready for a change. VanSumeren left the University of Michigan, the renowned Big Ten institution where he’d spent 20 years as scientist and pilot in the university’s Ocean Engineering Laboratory, and took a new post in Traverse City as director of Northwestern Michigan College’s fledgling Water Studies Institute.

The usual comments followed–from colleagues who called him crazy and from friends who thought he’d succumbed to a mid-life crisis. VanSumeren, however, was convinced that the same man who performed difficult and dangerous nautical missions from the Hawaiian Islands to the Alaskan Bering Glacier was also capable of taking a little-known community college water studies program into new and uncharted academic waters.

More than a year after the 40-year-old VanSumeren assumed the directorship, the Water Studies Institute has attracted more students, developed new curriculum, and launched the nation’s first and only program to confer a two-year associate’s degree in Freshwater Studies. Interest in the degree is prompted by new trends in policy, science, technology, markets, and environmental conditions that students believe will increase demand for workers trained in water resources.

The Water Studies Institute’s new program launched with the first classes in September. The 20 community college students—ranging in age from 17 to 54—enrolled in the program pursue a curriculum that uses Grand Traverse County’s 44 inland lakes and 132 miles of Lake Michigan shoreline as real-life textbooks and training manuals.

“Water has been polluted and abused for a long time without a lot of protection towards its future, but now people are starting to catch on,” says Kyle LaLone, 24, a third-year student attending the WSI program.

LaLone had intended to take a few courses at NMC and eventually transfer to another institution to finish his degree. But LaLone told Circle of Blue that he changed his mind when the Freshwater Studies degree was created.

“More emphasis is going to be placed on water in the future, and creating this new branch of jobs is going to be a big boost for the economy.”

The Program

“Students don’t just learn the tool, they learn how to apply the tool,” VanSumeren says, explaining the value of a hands-on education. Coursework includes studying invasive species, monitoring pollution in nearby lakes, and examining the environmental consequences of removing three old dams on the Boardman River just a few miles from the NMC campus.

With a degree in Freshwater Studies from WSI, graduates can continue on in a bachelor’s degree program at one of the six Michigan partner universities, or enter directly into industry jobs–working in wastewater treatment, stream data collection and analysis, or environmental and engineering consulting. The program optimizes hands-on experiences available to NMC’s students with in-the field opportunities, a research vessel, a float plane, internships, seminars with weekly guest lecturers, as well as a core curriculum in oceanography, earth science, meteorology, climatology, and watershed science.

“We have a lot of people who really want to do this kind of work, so let’s give them the opportunity to get as much education as they can here,” says VanSumeren in an interview with Circle of Blue. “Let’s give them assets that they could not get in their first two years at the University of Michigan, or Michigan State, or any of the larger universities where you are one of thousands—versus one in tens when you get to the smaller programs here.”

The NMC program also makes economic sense, he added. One year of in-state tuition, including room and board, at Michigan costs more than $20,000; NMC costs $2,800 to attend.

VanSumeren’s challenge in directing the Water Studies Institute has been considerable. The program, established in 2004, was staffed by contractors and spent much of its history as a professional enhancement vehicle for teachers—giving local community educators the chance to implement knowledge of the Great Lakes and freshwater science into their own classrooms. VanSumeren, who arrived in 2008, was the institute’s first full-time employee.

VanSumeren and his Colombian-born colleague, Dr. Constanza Hazelwood—who serves as the institute’s education and outreach coordinator—worked for more than a year to develop a curriculum that harnesses the assets of a community college on the coast of Lake Michigan. Their program offers “three streams” of inter-disciplinary concentrations—economy and society; global freshwater policy and sustainability; and science and technology, a pre-engineering track. For the global track, Hazelwood is coordinating a student research exchange program with universities in South America that could be implemented as early as next year.

“Michigan is near the 45th parallel and has a certain agricultural industry. If you go to the 45th parallel south of the equator you see similar crops grown—but they don’t have the same abundance of freshwater—how do they do that?” VanSumeren asks, emphasizing the benefits of a cultural exchange of ideas, methodologies, and skill sets on both sides of the border.

“You learn a certain set of skills and competencies and you should be able to take that a lot of places. Water allows us to do that,” VanSumeren says. Graduates will be able to take their water degree anywhere, “from Traverse City to China to Chile, then back to Tennessee,” he added.

His Credentials

Whether it’s luck, charisma, or some mix of the two, VanSumeren has shown himself capable of easily navigating through life’s many challenges. He originally met his wife-–they share the same birthdate and the same birth hospital—in high school, although it wasn’t until a chance meeting on the streets of Ann Arbor many years later that they connected. He inherited the waterfront house that they call home. And he never faced a job interview until he applied for WSI director.

Prior to his new post, VanSumeren was a researcher at the University of Michigan, where he worked for the Ocean Engineering Laboratory using different types of radar, backscatter, and remote sensing to characterize the ocean surface. He became an expert remotely operated vehicle (ROV) driver and was a member of expeditions that used the ROV to find shipwrecks all over the Great Lakes, as well as to investigate deep sinkholes in Lake Huron and Lake Michigan.

The underwater vehicle has been through its paces with VanSumeren in the pilot’s seat, so to speak. While researching in Maine, he used the ROV for seafloor mapping of lobster and scallop habitats. In the Florida Keys, VanSumeren used the ROV—equipped with special sensors to measure the health of the coral reef at multiple locations—to provide ground-truthing for a scanner that was flying above in an airplane.

“He’s one of the nation’s best underwater vehicle pilots,” says Dr. Guy A. Meadows, the director of the Ocean Engineering Laboratory, who described the ROV as a million-dollar toy. “He became very skilled at operating the vehicle on high-quality scientific missions.”

Sometimes trips turned bust, however, as was the case with VanSumeren’s “first ocean cruise” from Oahu to San Diego aboard the 160-foot long research ship, “New Horizon.” No data could be collected after the ROV flooded in Pearl Harbor, despite VanSumeren’s month-long efforts to fix it. Persistent, he completed the project four years later.

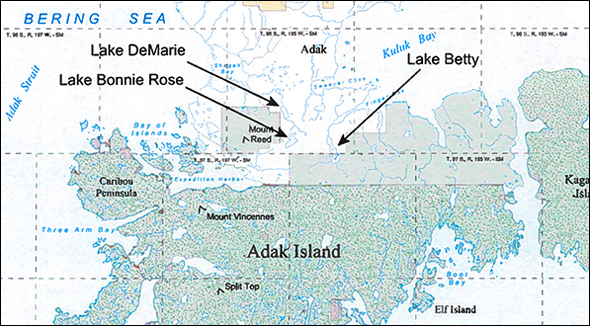

During a 2003 trip to Alaska, VanSumeren and Meadows worked with an international team studying the recently exposed areas of the Bering Glacier following the massive and rapid retreat of ice coverage. VanSumeren completed hydrographic mapping of Vitus Lake, aiding in the study of the hydrodynamics of the melting glacier—while keeping a close eye out for grizzly bears.

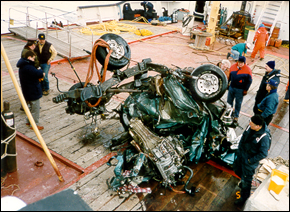

VanSumeren has also used the ROV to conduct body recoveries for law enforcement organizations. He helped retrieve a Ford Bronco that drove off the Mackinac Bridge in March of 1997 and—in spite of his busy schedule as WSI program director—in June of 2009, VanSumeren used the ROV to find the body of a lost swimmer in East Grand Traverse Bay.

Even though he once had the chance to pilot the SSBN 727-Michigan—a U.S. ballistic missile submarine—around the Hood Canal in Washington during a complete missile launch “simulating World War III,” VanSumeren says the real opportunities are only just beginning to unfold for him, and for the water community at large.

“We can make fuel. We can’t make water,” VanSumeren says. “If we price it, it’s a lot more expensive than oil.” When we start pricing water appropriately, he added, there will be large increases in job opportunities in water-related careers. As director of the WSI Freshwater Studies Program, VanSumeren sees himself as preparing students for that workforce.

The Transition

“I hated to lose him,” Meadows said of VanSumeren’s transition. Meadows had been VanSumeren’s undergraduate adviser long before he was his employer. “This was just too good to pass up. He has a lakeside office! I don’t have a lakeside office!”

Leaving Michigan behind was a relatively smooth transition for VanSumeren. He was raised in Traverse City and inherited a house next door to the one where he spent his childhood on East Grand Traverse Bay. He was the winning candidate among the more than 50 professionals who applied for the WSI position. And as an administrator, VanSumeren is still able to collaborate with Meadows and others at Michigan on research—only now the water he’s studying is right in his own backyard.

“We have all these nice pieces of equipment, like this remote-operated vehicle [owned by the State Police] that I have access to whenever I want,” VanSumeren says. “Plus the tools at Michigan–I still have a good relationship with them so they let me borrow their stuff. I still collaborate with them on research. So what did I really give up when I left? Not much.”

He’s also taking advantage of equipment available through NMC and building new partnerships. He’s turned the The Northwestern, a 56-foot ship once used by the federally recognized Great Lakes Maritime Academy based out of NMC, into a floating classroom. At Michigan, students don’t go out on research vessels until well into their second or third year of school, VanSumeren told Circle of Blue. His NMC students, however, set sail much earlier.

This summer, VanSumeren took students out on The Northwestern with state-of-the-art hydrographic survey gear to map the bottom of the bay. VanSumeren also collaborates with NMC flight students to increase efficiency in water testing. Based on his travels to remote lakes in Alaska, VanSumeren suggested that NMC use its float plane to reach lakes and streams for testing. In an eight-hour day, his students sampled 14 lakes at 22 sites—a task that would have taken at least two weeks by boat and car. The NMC flight students were already up in the air practicing their flying skills, so it didn’t cost anything extra to load the aquatic gear. The partnership through WSI and the flight school has continued, performing tests for both federal and state government agencies.

“We didn’t have planes at Michigan,” smiles VanSumeren.

“Coming from Michigan, a lot of people challenged me. ‘What are you going to do there? What do they have? You’re not going to have the same toys, the same activities, the same research,’” VanSumeren remembers of his last few months in Ann Arbor. “And I looked through what NMC had to offer, and I think very quickly it was, ‘You’re wrong. I have a lot more here than I do at Michigan.’”

“The atmosphere I get to work in here—you could not put that in Ann Arbor,” adds VanSumeren. “And of course there’s nothing better than getting home from work and going for a sail.”

Aubrey Ann Parker, an undergraduate student at the University of Michigan, is a reporter for Circle of Blue where she specializes in data visualization. Reach her at circleofblue.org/contact.

is a Traverse City-based assistant editor for Circle of Blue. She specializes in data visualization.

Interests: Latin America, Social Media, Science, Health, Indigenous Peoples

They might have said he is crazy when he made that big decision but surely, he has something bigger on his mind and he is working hard to get it. Way to go!