A Dry and Anxious North Awaits China’s Giant, Unproven Water Transport Scheme

Authorities anticipate approval for new western line to tap energy reserves.

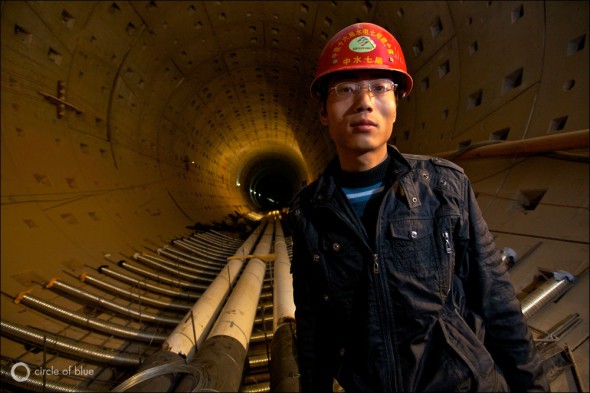

Photo © Aaron Jaffe / Circle of Blue The dark openings of two pipelines beneath the Yellow River, like eyes on a flat face of dirt and rock, are unblinking witnesses to the South-North Water Transfer Project.

By Aaron Jaffe and Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

UPDATE: China opens middle canal of the South-North Water Transfer Project (December 12, 2014).

ZHENGZHOU, China—Sparks and the blue flare of arc welders, like hot stars in the night sky, illuminate the interior of a massive water tunnel that crosses underneath the Yellow River. Outside, in a construction zone that encompasses both banks of the river, crews gouge a channel that sinks steadily deeper until it reaches the yawning mouths of two concrete pipes. The openings are so large, 18-wheel tractor-trailers could easily drive through.

The dark circles, like eyes on a flat face of rock and dirt, are unblinking witnesses to the South-North Water Transfer Project, a feat of natural hubris and hydrologic engineering spanning 12 provinces through 3,000-kilometers (1,900-miles) of canals and tunnels that is meant to accomplish something only China would attempt: replumbing an entire nation.

If scheduling and operations projections are accurate, in 2014 some 13 billion cubic meters (3.4 trillion gallons) of water per year will pour through the tunnels of the central line, under construction here in Henan Province, and will be sent north to help curb water shortages in more than a dozen cities, including Beijing.

The eastern line, a second transfer project, should already be operating by then, transporting 14.8 billion cubic meters of water annually from the lower Yangtze River to Tianjin.

And this month, in its new 12th Five-Year Plan—the official guide to national development—China is expected to approve construction planning for a third line, according to interviews Circle of Blue conducted with several authorities close to the project. The western line will transport an additional 8 billion cubic meters of water annually from the western Himalayan region to supply the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River in the north.

Taken together, the three lines of the South-North Water Transfer Project are an audacious strategy to solve a commanding threat to China’s modernization: the increasingly dire confrontation between rising energy demand in a nation that is steadily getting drier.

China’s plan is to remove nearly 36 billion cubic meters (9.5 trillion gallons) of water every year from the Yangtze River Basin—which drains much of the nation’s central and western regions—and ship it north. That is tantamount to reversing the flow of the Missouri River—which drains the Great Plains and part of the Northwest in the United States—and sending it back to Montana.

It’s no surprise that ever since construction began in 2002, the South-North Water Project has generated a strong current of public comment. China’s government authorities insist the project, now estimated to cost $US 62 billion, is essential to developing the cities and energy-rich provinces of northern and western China, the fastest growing regions in the country, which are running out of water.

“Transferring water from the south to north makes perfect sense,” said Wang Hao, director of the Water Resources Department at the state-run China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research in Beijing and one of China’s most influential government water scientists.

Wei Zhimin, a water expert in Hebei Province within a unit of the Ministry of Water Resources, said last year in an interview with Xiaoxiang Evening News that the South-North Project would not solve north China’s water crisis, but was nevertheless essential.

“Lifeline is one word to describe it,” Wei said. “And by lifeline, I mean a lifeline for north China, Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei included.”

But the project’s critics—among them academics, economists, and environmental leaders—assert that the magnitude and cost of building and operating the continental water transport system would produce a cascade of unintended consequences that could overwhelm the benefits to China. These consequences include much higher municipal, agricultural, and industrial water prices, damage to aquatic environments, additional treatment facilities for Yangtze water that is currently too polluted to use, and continuing water shortages shortages in northern China, and possibly in southern China, too.

“We should take no pride in doing such a project,” said Ma Jun, an author and the director of the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, a non-governmental organization in Beijing. “This is a moment for us, a sobering moment for us, to reflect upon how we drove ourselves to such a situation.”

Big Projects in China’s DNA

The answer to that statement is readily available. Infrastructure projects designed to solve big national problems and that achieve otherworldly scale are a cultural priority as old as China.

The 2,500-year-old, 5,500-mile Great Wall of China was designed to safeguard the nation from northern invasion. More recently, China finished the Three Gorges Dam in 2008, which generates as much electricity as 25 big coal-fired plants, holds back 600 kilometers (375 miles) of the Yangtze River, and is so big that it makes the Hoover Dam—the iconic U.S. water engineering project of the 20th century—look like a bathtub toy.

But history has shown that the Great Wall has more cultural usefulness as a modern income-generating tourist attraction than it ever did as an ancient deterrent to invasion. And some scientists have blamed the Three Gorges Dam for putting pressure on an unstable earthquake fault line and causing deadly landslides.

In effect, there are sound reasons for a good number of Chinese to wonder whether the South-North Water Transfer Project will transport enough water to ease northern China’s water emergency. And if it doesn’t, what is China’s Plan B for supplying enough water so that the dry northern and western provinces—where most of the nation’s big and water-thirsty fossil fuel reserves are located—can continue to develop?

“What if we don’t transfer water?” said Ma. “We probably could have a collapse of the economy in some of the cities, which are going to run out of water. It will not really resolve the whole problem, though. It will mean that, even with this, it cannot fill even the current existing water shortage gap, let alone that much bigger water gap in the future.”

A Product of Policy

The South-North Water Transfer Project was one of the infrastructure centerpieces of China’s 10th Five-Year Plan that set economic development priorities from 2001 to 2005. It was seen as a critical step in Chinese President Hu Jintao’s “Scientific Development Policy,” which relies on engineering, technology, and modern policy to address the nation’s important resource challenges.

Other components of the water and energy policy include developing and enforcing water conservation and efficiency statutes that require industries and cities to recycle and use less water.

China has since taken millions of acres of cropland out of production and required farmers to use new water-conserving irrigation practices. The country launched world-leading production programs for wind, solar, and seawater-cooled nuclear power that use much less fresh water. And China is investing huge sums in the coal production and combustion sector—which supplies 70 percent of the nation’s energy—to reduce water consumption in mining and processing, in addition to building coal-fired generating stations that are either air-cooled or 20 percent more water-efficient than conventional power plants. (Reports on water use in the coal sector are upcoming in this Choke Point: China series.)

A Drying Nation Needs More Energy

Certainly, President Hu and other leaders understand the mammoth dimensions of what China faces. Some 80 percent of China’s freshwater reserves lie in southern watersheds like the Yangtze River Basin.

The Chinese Ministry of Water Resources estimates that national water consumption— 599 billion cubic meters in 2010, according to just-released national figures—will increase by nearly 1 percent annually and may reach as much as 670 billion cubic meters by 2020. A good portion of the increase will go toward developing coal reserves in the fast growing northern and western provinces that are now too dry to tap.

Yet, even as national water use steadily increases total water resources are decreasing, and China is becoming progressively drier, according to government figures. In 2009, total freshwater reserves dropped to 2.42 trillion cubic meters, 353 billion cubic meters less than in 2000, which represents a 13 percent decline. China, this week, reported that total water resources rebounded in 2010 to 2.87 trillion cubic meters, the highest level since 2002.

Chinese scientists and climatologists blame climate change for the erratic water levels. The warming planet, they say, is wreaking havoc with rain and snowfall. Southern China endured searing droughts in 2000, 2007, and 2009. This winter, the worst drought in 60 years settled onto Beijing, as well as the northern and eastern provinces.

Longer and deeper droughts, coupled with China’s growing recognition of the consequences of rapid industrialization on the quality of the nation’s air and water, prompted Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao and Environment Minister Zhou Shengxian to issue insistent warnings this week and lower national development targets. Zhou said on Monday this week that China would establish a new system of assessing whether development projects contributed to climate change. And Wen said the country would lower its annual domestic growth to 7 percent — from more than 10 percent annually in recent years — and press national leaders to tighten environmental safeguards.

“We must not any longer sacrifice the environment for the sake of rapid growth and reckless roll-outs, as that would result in unsustainable growth featuring industrial overcapacity and intensive resource consumption,” said Wen in an Internet interview.

Government officials assert that the South-North Water Transfer Project is an answer to water scarcity that is coming at just the right time. The basic math looks good. The eastern and central lines could provide close to what the government estimates will be needed by the middle of the decade, when the lines are expected to begin operation: 27.8 billion cubic meters (7.34 trillion gallons) of water annually. And much of the balance could be supplied when the western line is finished, decades from now.

But what looks to some government agencies as a neat path for avoiding a ruinous collision between China’s accelerating growth and scarce freshwater reserves, appears to other authorities as a complex and expensive plumbing system that will be exceedingly difficult to operate.

Three of the most significant problems already have emerged:

- High Water Prices. Because water from the transfer project will be very expensive, Tianjin and other cities that will serve as destination ports are currently looking into other options. Desalination plants could turn seawater into fresh water at considerably lower cost than what it would take to ship water in from afar, said city managers. New desalination programs are currently being launched. “The unit water cost of desalination is actually cheaper than that of the South-North Water Diversion Project,” Zou Ji said in an interview with the Asia Water Project, a research group, last month. Zou is a professor of environmental economics and management at Renmin University in Beijing, “Many coastal cities, including Tianjin, Qingdao, and Dalian have integrated desalination into their middle-to-long-term blueprints as an alternative water resource.”

- Timing and Destination. The western line is the only one of the three transport lines that will deliver water directly to the Yellow River Basin, the primary water supply for the energy-rich northern and western provinces. Moreover, if the western line is constructed as several authorities predict, it won’t be finished for at least a few decades. By 2020, China’s demand for coal is projected to grow by 1 billion metric tons, a 30 percent increase. But most of the new reserves of coal that would be tapped lie in Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, and Ningxia—provinces, supplied by the Yellow River, that are too dry to develop, since coal production and combustion uses vast amounts of water.

- Pollution. Chinese and international organizations report that the water due to be transported in the eastern line, sourced from the lower Yangtze, is too fouled with industrial and municipal pollutants to use, even though it would have already passed through the more than 400 water treatment plants and pollution control projects China has built to remediate the river’s pollution.

The Last Big Barrier: Water Supply

A fourth barrier to the project’s success, one that would have been considered ludicrous a decade ago, also has become more apparent in recent years: the southern China watersheds tapped by the transfer project may eventually not have enough water to supply the dry north.

The mighty Yangtze, the third longest river on Earth and principal supplier of water to the north, drains watersheds in the south central and western regions of China. As recently as 1999, according to the Ministry of Water Resources, the Yangtze River Basin contained over 1 trillion cubic feet of water, or 36 percent of the nation’s total water supply.

But like almost every other region of China, the water-rich south, too, is steadily losing moisture. In 2009, the latest year for accurate figures, total freshwater reserves in the Yangtze River Basin had dropped 172 billion cubic meters, or 17 percent, from 2005 levels, according to the China Statistical Yearbook.

The new data has prompted southern provinces, like Sichuan, to express sharp concerns over the diminishing water supplies and to file formal oppositions to building the third and final transfer line in the west.

“The problem is to coordinate the interest relations between the supply region and the transfer region,” said Tan Yingwu, the western line’s chief, who thinks the political and cultural resistance can be resolved. “Transferring water from one region to another is some people’s gain and other people’s loss. How to coordinate their relations, and how to compensate one’s loss, is an important problem.”

Still, authorities close to the central government say the western line will be built. China’s important northern provinces need the water.

“The Yellow River Basin has very little water, but this area has to supply 70 to 80 percent of the energy in the country,” said Shaofeng Jia, vice director of the Center for Water Resources Research at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. “Developing this requires the west line of the transfer.”

Aaron Jaffe—who has reported from China, Australia, and the United States—is a Chicago-based reporter and photographer for Circle of Blue. Keith Schneider is Circle of Blue’s Traverse City-based senior editor. Wang Zhuo contributed reporting from Beijing.

Reach Jaffe and Schneider at circleofblue.org/contact and contact Keith Schneider directly.

Map and graphic by Stephanie Stamm, Justin Manning, Stephanie Meredith, and Kate Roesch, undergraduate students at Ball State University, with contribution by Nadya Ivanova, a Chicago-based reporter for Circle of Blue, and Jennifer Turner, director of the China Environment Forum within the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Reach Ivanova at circleofblue.org/contact.

The Choke Point: China series is produced in collaboration with the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars China Environment Forum.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

That’s a really big pipe.