Circle of Blue’s China Tour Finds Strong Reception for Water-Energy Choke Point Warning

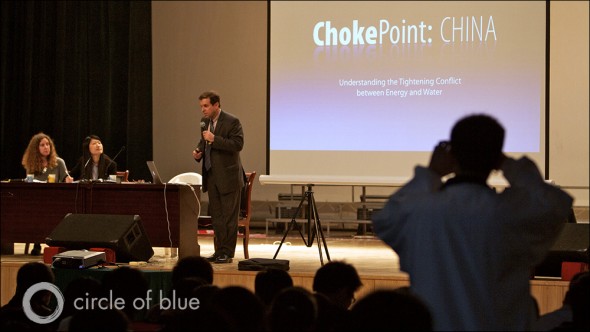

Circle of Blue and the Wilson Center’s China Environment Forum present at 17 events in 4 cities over 16 days.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

YINCHUAN, China—The morning we travel north from this provincial capital, following the Yellow River to the Nan Liang Migration Farm, Kou Guojiang greets our arrival with a smile and a farm-fresh breakfast. It is April 13, and the bright sun lights a long table set with big purple grapes, miniature oranges, thin slices of watermelon, cherry tomatoes, and crisp red apples so cold they perspire in the warming air.

Kuo is the 46-year-old chairman of the Nan Liang farm’s water user association, which supplies Yellow River water to 300 farm families who irrigate and cultivate 200 hectares (494 acres) of corn and wheat. It is the 14th day of the Choke Point: China research and speaking tour, and the first visit on this trip by our five-person team to a rural area.

Kuo is gracious, clear-eyed, and not at all shy. He tells us that in 2003 the government relocated the association’s families from a very dry region in southern Ningxia, where crops frequently failed for lack of moisture.

Now he worries that similar conditions are unfolding on the Nan Liang farm, where persistently dry weather and competition from new coal-based industries have prompted government water managers to cut allotments to the association by 10 percent a year since 2008. Yet, despite the diminishing supplies of water and 53-year-old, unlined, water-wasting, sand-filled irrigation canals that transport it to their land, Kuo says harvests have increased.

He says that technical assistance from the World Bank and other institutions helped the association’s farmers to increase their harvests, even as they use 30 percent less water.

“If we had good canals, we’d be able to save even more water,” Kuo says.

Meeting Eager Audiences

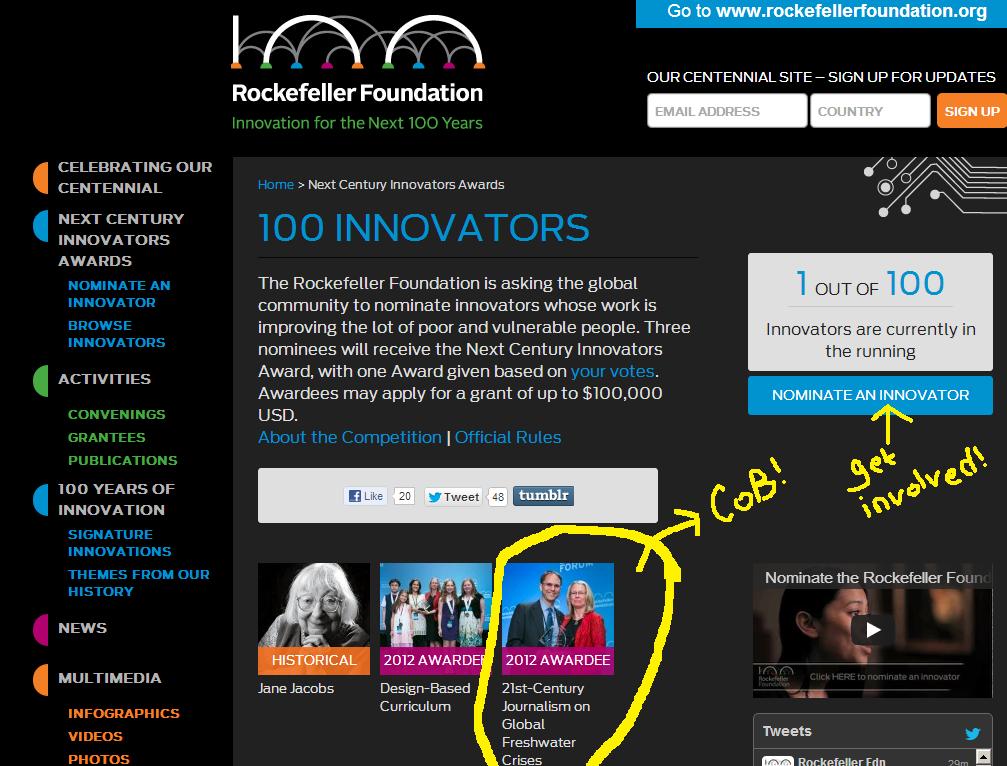

Since mid-February, in probing weekly reports from our Choke Point: China series, Circle of Blue and the China Environment Forum of the Washington-based Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars have for the first time revealed the increasingly fierce competition between energy and water that threatens to upend China’s progress.

In late March, the two organizations arrived in Beijing for the start of a 16-day trip that took three reporters from Circle of Blue and two researchers from the China Environment Forum to Beijing and Shanghai in eastern China and then to Chengdu and Yinchuan, in the nation’s south and west. The tour, supported by the Energy Foundation and Vermont Law School, also included Adam Moser, the China Environment Fellow at Vermont Law School, who joined us at events in Beijing and Shanghai.

Much of our time was spent describing the project findings to gatherings of academics, business leaders, scientists, environmental NGO staffers, students and diplomats. Some groups—like the April 11 meeting with environmental leaders at the Conservation International office in Beijing—were small enough to fit around a conference table. The largest event was at Ningxia University, which was attended by 1,100 students and faculty members.

Our itinerary also included meetings with American diplomats at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, with scientists, faculty, and students at the Shanghai Academy of Environmental Sciences and Tsinghua University, and with leaders of the Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, a think tank of the Ministry of Water Resources, the national government agency that oversees China’s freshwater reserves.

Beijing: We Have A Problem

Our central message—which was seen as new and urgent by participants in all of the events—is that China’s soaring economy, fueled by an unyielding appetite for coal, is already buffeted by the country’s steadily diminishing freshwater reserves. Next to agriculture, China’s coal mining, processing, combustion, and coal-to-chemicals industries consume more water than any other industrial or commercial sector.

More than 70 percent of the nation’s energy is generated from coal. And even with China’s enormous program of energy diversification—leading the world in renewable sources, such as hydropower and wind power—the nation will not reduce reliance on coal and water much by the end of the decade. By 2020, China’s electrical generating capacity is expected to double to 1,900 gigawatts, up from 960 gigawatts last year. At least 500 GW of new generating capacity, according to Chinese estimates, will be generated by coal. China’s coal production, 3.15 billion metric tons last year, is expected to increase to more than 4 billion metric tons by 2020.

The nation’s coal reserves are enormous, but they lie beneath the deserts of China’s northern and western provinces—Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Ningxia—where annual rainfall is measured in mere millimeters.

As we explained in our briefings, China’s principal energy-water choke point is the result of rocketing coal-based energy demand confronting water scarcity in this drying landscape. From 2000 to 2009, China’s total water reserves have fallen 1.5 percent annually—35 billion cubic meters (9.2 trillion gallons) of water a year—or 350 billion cubic meters (92.5 trillion gallons) of water lost during the decade, according to China’s Ministry of Water Resources. That is roughly as much water as the Yangtze River pushes past Shanghai in eight months.

Simply put, even with new water-sipping energy-generating technology, China does not have enough water in its dry north to modernize at its current pace. The confrontation between energy and water, we explained, is certain to grow worse.

Over the next decade, China’s total water use will increase from 599 billion cubic meters (158 trillion gallons) in 2010 to 670 billion cubic meters (177 trillion gallons) annually by 2020.

Not Enough Water

Of the 71-billion-cubic-meter (19-trillion-gallon) increase, according to Chinese analysts in academia and the government, 50 billion cubic meters (13 trillion gallons) will be needed by the coal sector—though this figure could be cut if certain upgrades are made.

National programs for improving energy efficiency and water conservation, for generating power without fossil fuels could reduce water use by 10 billion cubic meters (2.6 trillion gallons) annually. In addition, transporting water from China’s wet south to its dry north will simultaneously provide 20 billion cubic meters (5 trillion gallons) of water to the drying region.

But nobody in China has yet identified how the northern and western coal sector will secure the balance—20 billion cubic meters (5 trillion gallons) of fresh water—that the coal industry will need each year by 2020.

These and other findings from Choke Point: China were greeted with a mix of intense interest, respect, and a good measure of surprise by Chinese audiences, particularly from scholars and government officials.

Dr. Changhong Cheng, the deputy engineer in chief of the Shanghai Academy of Environmental Sciences, said he had read the online Choke Point: China reports and called them “stunning.” He said the findings had compelled him to recommend that the academy revise its research agenda on energy and water, as well as its teaching curriculum.

Dr. Yangwen Jia, a chief engineer of the Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, called the findings “impressive” and said they had compelled him to look at China’s water resources from a new vantage. He said his group had never undertaken research to understand the developing confrontation between the coal sector and water scarcity in the northern and western provinces.

Just Show Up

In nearly every event, we were asked how Circle of Blue had amassed such telling facts and a fresh narrative about energy and water in China.

We explained that because China compartmentalizes its data on water and energy within government agencies and academic units, individual organizations study specific aspects of each but rarely share their findings with each other.

In order to collect the data, Circle of Blue followed film director Woody Allen’s dictum—“80 percent of success is just showing up.” In December, our research teams traveled to the cities, the research centers, the industrial plants, and the government agencies to collect the facts that produced Choke Point: China’s new narrative.

That is how we learned that Kou Guojiang and his colleagues on the Nan Ling water user association’s board had helped 300 farm families to grow as much food as they did in 2008, but with 30 percent less water. These gains in water efficiency reflect the second part of the Choke Point: China narrative: if any nation is capable of solving such a large confrontation between two vital resources, it is China.

There are plenty of examples. For instance, as we noted in an earlier Choke Point: China report on the Ningxia Autonomous Region, where 6.3 million people live and where the economy grew 13.4 percent last year, industrialists and farmers have worked out a water-transfer program. The agreement enables the Ningdong Coal-Chemical Manufacturing Base to expand, while still supplying the region’s farmers with sufficient supplies of water without draining the basins. The industrial companies paid for irrigation efficiency upgrades, and the water that is saved—100 million cubic meters (26.4 billion gallons) annually—was “transferred” from agricultural use to industrial use.

The central point of Choke Point: China is that the world’s largest nation and second-largest economy faces an unavoidable confrontation between its two most important resources, energy and water. We learned from our reporting in December, and again during the April trip, that this is a collision that China understands and has anticipated, but only in specific dimensions and not nearly as a systemic threat to modernization. We were told repeatedly by some of the country’s leading energy and water experts that Choke Point: China provides new data and a never-before-heard narrative of urgency that will help a determined country avoid a collision that would be felt around the world.

Keith Schneider—who has reported on energy, water, and climate change from four continents—is a Traverse City-based senior editor for Circle of Blue. Contact Keith Schneider

The team included J.Carl Ganter, Keith Schneider, and Nadya Ivanova from Circle of Blue, Jennifer Turner and Peter Marsters from the China Environment Forum at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and Adam Moser from Vermont Law School.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!