Bohai Sea Pipeline Could Open China’s Northern Coal Fields

Disputed project seen as a must for modernization.

By Keith Schneider

Sidebars by Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Photographs by J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue and Toby Smith/ Reportage by Getty Images for Circle of Blue

XI’AN, China—Last November, as government leaders considered energy goals for China’s upcoming 12th Five-Year Plan—which was adopted last month—60-year-old geographer Huo Youguang took the podium at an academic meeting about water scarcity and coal production in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, one of the driest inhabited areas on the planet.

Over the next half-hour or so, Huo described a first-of-its-kind transcontinental pipeline that he believed could be a breakthrough in developing more fossil energy from Xinjiang and China’s other northern coal-rich provinces, while conserving the region’s scarce freshwater reserves.

His proposal: drop a pipe into the Bohai Sea in China’s east, draw more than 340,000 cubic meters (90 million gallons) of seawater a day into a complex of coastal desalination plants, and then pump this water 1,400 meters uphill for more than 600 kilometers (nearly 400 miles) to Xilinhot, where it will be used for coal mining operations.

By the time Huo finished his presentation, he’d ignited a national engineering debate surrounding the cost, practicality, and feasibility of using vast amounts of purified seawater to produce more coal for China’s modernization, while simultaneously easing northern China’s water shortage. By suggesting a giant project that some authorities considered daffy, Huo also confirmed just how vulnerable China’s powerful engine of growth is to deepening water scarcity, particularly in the energy-rich northern and western provinces, now the primary focus of China’s development and modernization.

Xilinhot, an Inner Mongolia city of 177,000, lies atop a mammoth and, so far, untouchable coal reserve. Chinese authorities estimate Xilinhot’s proven and unproven coal reserves to contain 1.4 trillion metric tons. At China’s current rate of coal production—more than 3 billion metric tons annually—the Xilinhot reserves alone could power the country for the next 425 years.

If the first $US 6 billion stretch of the Bohai Pipeline were to perform as Huo anticipates, it could be expanded and sent an additional 2,800 kilometers (1,850 miles) from Xilinhot—crossing the rest of Inner Mongolia and through northern Gansu Province—all the way to the western province of Xinjiang, where Chinese geologists say even larger coal reserves exist. Leaders are pressing the region to double current coal production capacity to 200 million metric tons of coal per year by 2015.

Collision Approaches

As China rushes deeper into the second decade of the 21st century, the nation’s energy production and consumption trend is a steep, increasing line. It is that vector— fast-rising energy demand confronting water scarcity—that is proving so difficult to resolve.

Huo Youguang, a professor in the Center for Environment and Modern Agriculture Engineering at Xi’an Jiaotong University in Shanxi Province, is convinced a transcontinental pipeline will help.

Back in December, Huo told Circle of Blue that the rapid transformation of the growing and modern desert cities of Inner Mongolia, Gansu, Xinjiang, Ningxia, and Shanxi provinces are endangered by their diminishing freshwater reserves.

These regions contain the nation’s largest proven and unproven coal reserves. But developing coal reserves, along with the power and processing infrastructure to consume coal, uses tens of billions of gallons of water each year—water that isn’t available in a region that receives just a few inches of rain annually and where climate change is reducing snow pack.

“We need water, and the sea can provide it,” Huo said, noting that he had first proposed an across-the-north route for a pipeline from the Bohai Sea back in 1997.

In 2002, a separate academic team from Beijing University proposed a similar route, but further to the north. However, both pipelines—which would transport water more than 3,400 kilometers (2,100 miles) to Xinjiang—are seen by a number of Chinese engineers as impractical.

And even if the pipeline were built, say critics, would it really be capable of slaking the big thirst of northern China’s coal sector?

Evading Water-Energy Choke Point, For Now

Of all the threats over the next decade to China’s rapid modernization, arguably none is more significant than assuring adequate supplies of coal, which accounts for 70 percent of the nation’s total energy production and consumption. In the previous chapters of Choke Point: China, Circle of Blue has reported the essential outlines of a potentially ruinous and fast-approaching confrontation between rising demand for coal and steadily diminishing freshwater reserves.

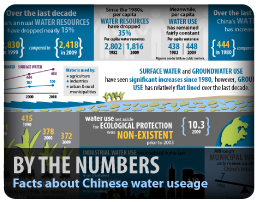

To date, China has managed to largely evade the water-energy collision. Once regarded as one of the world’s worst water wasters, since the mid-1990s, China has enacted and enforced water-efficiency and water-conservation measures for industries, cities, and agricultural lands.

Proposed industrial plants are required to assess the availability of water in the surrounding region and prove there is enough for plant operations and processing prior to construction—and then they must recycle water used during manufacturing and processing.

China’s big cities, led by Beijing, are erecting new buildings that include a “gray water” plumbing system—kept separate from potable tap water supply—that delivers recycled wastewater for washing cars and flushing toilets. In 2009, there were about 200 Beijing communities receiving gray water; most of these were economically affordable housing units, since the price of gray water is reduced by government subsidies and is therefore much cheaper than tap water.

Since 1998, according to national records, China has taken 8.5 million hectares (21 million acres) of farmland out of production, while also improving irrigation practices on millions of additional hectares of cropland. In 2010, according to China’s Ministry of Water Resources, agriculture used 359 billion cubic meters of water, or 60 percent of all water used in China last year. As recently as 1990, China’s farmers used 83 percent, of all water used nationally.

China is nearing completion of a mammoth water-transport project from the south to the dry north, along with launching the world’s most-aggressive programs for building water-sipping wind and solar power plants in its northern deserts, seawater-cooled nuclear plants along its coast, and hydropower dams in its southwest—all of which provide more power, while reducing coal consumption and water use.

All of these water-saving measures helped keep the increase in water use to just 16 percent—or about one percent annually—from 1995 to 2010. During the same period, China’s GDP grew almost eight-fold and industrial water use increased by close to 50 percent.

In China, Coal is King

Over the last decade, China’s economy—the world’s second largest—has grown about 10 percent annually, fueled primarily by soaring coal production.

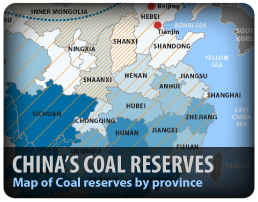

Last year, China produced 3.15 billion metric tons of coal—three times more than in 2000—much of it mined and processed in six northern China provinces. Inner Mongolia alone produced 782 million metric tons, ahead of the 741 million metric tons produced in neighboring Shanxi Province. Chinese energy experts and academics anticipate that, at current levels of growth, the country will need to produce over 4 billion metric tons annually by 2020 to keep up with demand.

But the driest regions in the nation are the very same northern provinces where much of the coal lies.

From 2004 to 2009, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, Inner Mongolia lost 46.8 million cubic meters (12.3 billion gallons) from its total freshwater reserve, or a drop of 15 percent. During the same period, Xinjiang lost 95.5 million cubic meters (25.2 billion gallons).

China’s goal is to meet energy demands, save water, and use the one fossil fuel that it has in abundance. The nation is pursuing multiple paths for assuring its coal supply—generally from existing mines—with the water it has. But new northern coal reserves can’t be developed without more water, coal industry executives and academic experts told Circle of Blue.

In the mountains and deserts of Inner Mongolia, the deep mines of Ningxia and Shanxi provinces, the buckled roads of Shanxi, and the jammed railroad lines of Hebei, China is pursuing its coal-based economic strategy with a fervor unmatched by any other nation.

North of Baotou—an Inner Mongolia city of 1.5 million—a double-tracked rail line lies along the northern shore of the Kunlin Reservoir. Every six minutes or so, the low whistle of a single diesel locomotive sounds across the lake, and a long train of 40 coal-loaded railcars rattles into view. All day long, seven days a week, loaded trains pass the reservoir, hauling coal from nearby mines to power plants, steel mills, and coal-to-chemical refineries.

China transports two-thirds of its coal by rail, according to national figures. The rail system is clogged with traffic and close to reaching capacity.

The other third—more than 1 billion metric tons a year—is shipped by truck.

China’s truck manufacturing industry is soaring, as is the price of diesel fuel, pushed by rising demand and languishing supplies. Outside Baotou, the two-lane road to the Daqing Shan open pit coal mine is being ground to pulverized asphalt under the wheels of thousands of coal trucks, hauling 80-tonne loads. China’s heavy truck dealers sold 1 million vehicles in 2010, a 60 percent increase from 2009, according to China Truck. In 2000, according to ChinaSignpost.com, an American Web site that follows China trends, heavy truck sales totaled 83,000 vehicles.

In northern China, coal truck traffic produces huge tie-ups that can take hours to clear. Last August, for example, traffic heading to Beijing on Hebei Province’s Dongyanhe Highway was so heavy that it caused a 100-kilometer (62-mile) traffic jam that took two weeks to clear.

At the Shenhua Group’s underground mine near Ordos in Inner Mongolia, miners manage machines that claw nearly 14 million metric tons of coal annually from a seam beneath the desert. Much of the coal is processed and then sent down the road to supply one of China’s four new coal-to-liquids refineries that produce diesel fuel.

Omnipresent candy-cane-striped smoke stacks, rising in clusters, pour clouds of eye-stinging and lung-clogging pollution into the air of nearly every major Chinese city.

Across the northern provinces, Chinese energy companies and utilities are constructing state-of-the-art coal-fired power plants. More than 20 “supercritical” and “ultra-supercritical” coal-fired power plants—which produce 10 to 20 percent more electricity per ton of coal consumed and which use 15 to 20 percent less water by burning hotter and at higher pressure—have been built. In the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, several other coal-fired power plants have been built, each one saving 70 to 80 percent of the water needed to cool a conventional coal-fired plant by using an air-cooling system instead.

In the city of Tianjin, south of Beijing, a consortium of coal companies and utilities is building the $US 1 billion, 650-megawatt GreenGen Power Plant. The coal-fired gasification plant—which has the capacity to be cooled by freshwater or seawater—is a demonstration project to produce energy more efficiently, as well as to capture and permanently dispose of climate-changing carbon emissions.

“The freshwater and seawater systems are in parallel,” said S. Ming Sung, an engineer and the chief representative in Asia for the Clean Air Task Force. “Obviously that costs more; but China is smart enough to test both systems. As they build more, the costs will come down.”

More Water Needed

Still, underlying northern China’s expanding coal sector is a growing need for more water in a region where access to freshwater is getting steadily more difficult.

By 2020, according to government projections, total national water may rise to 670 billion cubic meters (177 trillion gallons) annually—up from 599 billion cubic meters (158 trillion gallons) in 2010—and the coal sector’s share of national water use will rise to 27 percent from about 20 percent in 2010.

Much of the increase is due to the growing need for more coal—and more power plants to burn it.

Next to agriculture, the production and consumption of coal is the largest industrial user of fresh water. Last year, the coal sector used 120 billion cubic meters, or more than a fifth of the 599 billion cubic meters of water that China used nationally, according to the Ministry of Water Resources. All that water was devoted to mining and processing coal, cooling power plants, powering cement and steel plants, and turning an estimated 470 million metric tons of coal into fuels, chemicals, synthetic gas, and other products.

China’s big 1,000-MW coal-fired power plants use upwards of 3,800 cubic meters (1 million gallons) of water per hour for operations and cooling. This equates to 76,000 cubic meters (20 million gallons) a day, or 26 million cubic meters (7 billion gallons) a year.

China’s electrical generating capacity from coal was 750 GW in 2010, and is heading toward 1,250 GW in 2020, according to government projections. In other words, even with the new fleet of efficient plants, China’s coal-fired power plants alone will use roughly 34 billion cubic meters (9 trillion gallons) of water annually by 2020.

The growing coal-conversion sector will also increase water use. Depending on the product—diesel fuel, chemicals, natural gas—for every metric ton of coal converted, three to 15 metric tons (three to 15 cubic meters; 790 to 4,000 gallons) of water is used. China’s coal conversion program is currently consuming more than 5 billion cubic meters (1.3 trillion gallons) of water annually, according to engineers, and will continue to expand.

Lastly, the increasing level of technology and sophistication of China’s power plants are requiring a higher quality fuel. More coal than ever before, as a result, is being washed with water to remove impurities.

Wu Ying—the senior engineer at Beijing Huayu Engineering Company, which supplies the industry with technical advice—told Circle of Blue that 55 percent of all coal is now washed, up from 30 percent a decade ago. Washing coal takes 0.11 to 0.15 cubic meters (30 to 40 gallons) of water per metric ton of coal, or 178 million to 238 million cubic meters (47 billion to 63 billion gallons) of water annually.

Wu and other authorities say China is intent on providing energy with its own domestic supplies, which is why China is counting on ever-increasing coal production from the dry north.

Last week, Chinese officials bolstered that point when they announced that the provincial government of Inner Mongolia is following the trend already set by Shanxi Province, the country’s second-largest coal producer. Inner Mongolia will, over the next three years, shift the scale of mining operations from many smaller mines to a small number of large mines. Inner Mongolia counts 353 mines currently. That number could be reduced to 20 large-scale coal mining companies by 2013.

Experts said the restructuring would benefit the regional coal industry because the larger companies will be more efficient in using financial and water resources. Additionally, the Inner Mongolia government said that a number of the new and larger coal companies will have the capacity to produce more than 100 million metric tons annually, which makes access to water essential to the government’s plan.

In Xi’an, geographer Huo Youguang considered these new coal production trends in laying out the case for the Bohai Pipeline, which he argues is essential to China’s modernization. Huo said he is working with a desalination company and the Xilinhot government on a feasibility study for just the first 600-kilometer section.

“The project is technically feasible and necessary,” Huo told Circle of Blue. “I’ve thought about China’s water problems for a long time; building this pipeline solves that problem for this century.”

Keith Schneider—who has reported on energy, water, and climate change from four continents—is a Traverse City-based senior editor for Circle of Blue. Brett Walton is a Seattle-based reporter for Circle of Blue. Contact Brett Walton or contact Keith Schneider .

Map and graphics by Season Schafer, Greg Hudson, Valerie Carnevale, Chelsea Kardokus, and Vicki Rosenberger, undergraduate students at Ball State University. Photos by J. Carl Ganter, a Traverse City-based photojournalist and director of Circle of Blue, and Toby Smith a British photojournalist, represented by Reportage by Getty Images, who specializes in global energy and environment matters. Smith’s further work can be viewed on his website, and he can be reached at toby@shootunit.com.

Contributions by Jennifer Turner, Washington, D.C.-based director of the China Environment Forum at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Research assistance by Emily Li, Kexin Liu, and Zifei Yang.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

This article very well illustrates the need to provide full accounting of all water and energy costs when any new water or energy development project is proposed. For instance, this coal development project requires water that will come from desalination. That desalination process itself requires a tremendous amount of energy; this “energy overhead” should be accounted for and reported as part of the project proposal. Additionally, the production of energy to power the desal plants will itself likely require considerable water use; this “water overhead” should similarly be reported. When this full-cost energy and water accounting is reported, other means of securing fresh water — such as by improving irrigation efficiencies and urban water conservation — start to look extremely attractive, by comparison.

While not mentioned in the article, this coal and water desalination project is likely connected in some way to a huge new water development project already underway in Xinjiang Province. Agricultural overuse of water in the Tarim River Basin has completely dried up the lower river for more than three decades. To replenish the water of the basin and sustain agricultural production, the Chinese are building a 3500-km pipeline to move desalinated water from the Bohai Sea to the Tarim basin — this is equivalent to pumping water from the Chesapeake Bay and transporting it to California’s Central Valley!

I agree. Modern plumbing helps to ensure air gaps and physical separations between waste and clean water pipes. Regular plumbing maintenance can prevent cross-contamination.