Do It and Prove It—Information Technology Opens Up the Water Sector

Organizations are creating tech tools to shine light on water supply operations—and improve service.

Circle of Blue

Pressed by the need to provide clean drinking water for nearly 900 million people, a new generation of innovators is creating technology tools and an information economy that will transform water supply accountability and empower customers to demand better service from their water providers.

Among the most popular and effective new tools are mobile phones and mapping technologies that rely on rising access to wireless Internet connections and cloud computing to facilitate the flow of information. These devices, along with the software to link them together, show which supply projects are functioning and when water will be available to customers. By deploying this and other new technologies—including data monitoring and water quality testing—water advocates and service organizations are taking a serious look at project outcomes in order to learn from their failures.

The newly developed practices are replacing procedures that became global standards—build a water pump, add a new connection to a city’s trunk line, and hope that service reaches those who need it.

Yet, tracking whether these projects held up in the long run was less important than accumulating assets—or donors—on the construction side of the balance sheet. Quite often, failure was the result, as the uncounted mass of broken water projects and dissatisfied public service customers in the developing world would attest.

Tapan Parikh, a professor in the information school at the University of California-Berkeley, divides the sector’s information economy in two:

- Tools focused on improving the performance of governments, water aid groups, and other institutional actors.

- Tools providing information directly to customers regarding services that affect them.

“Institutions, like non-governmental organizations, can become more accountable, connect with their constituents and monitor their projects with better information,” Parikh said in an interview with Circle of Blue. “At the same time, the individuals we are trying to reach with these products aren’t well connected, either socially or through traditional infrastructure. Information technology can mitigate this isolation.”

A number of organizations and businesses are developing tools catering to both sides.

- NextDrop, a start-up company formed by graduate students at UC-Berkeley, is attempting to use data gathered from cell phone users to predict when water will be available in cities with intermittent supplies.

- Water for People, an NGO, is using data-tracking technology from Google to show, in real-time, how its water supply projects are performing.

- The H2.O Initiative, a group of water aid organizations, is highlighting a bundle of water monitoring and evaluation tools.

Call On Me

Just 15 years ago in the western world, having a cell phone was a status symbol, the currency of “cool” for the smart set. In some ways, conspicuous consumption is still evident with flashier phones packing an electronics store into a handset. But for many of the world’s cell phone users—especially in developing countries—the device is as much a lifeline as it is an untethered phone line.

As mobile networks have proliferated in the last decade, the phone’s utility has grown. Farmers in Uganda use their phones to check market prices of their crops, which inform them where they can earn the most. People in Kenya use a mobile banking service to transfer funds and make payments in places where brick-and-mortar outposts do not exist. The six countries that make up the Mekong River Basin use mobile networks to spot disease outbreaks and track their spread.

New possibilities for using cell phones to improve the water supply sector are being tested by a group of graduate students from UC-Berkeley. Their project, called NextDrop, uses the power of crowds and widespread cell phone coverage to predict water availability in urban areas that lack around-the-clock supplies.

— Ari Olmos

NextDrop

When water starts flowing, a customer signed up to NextDrop’s service sends a text message or calls a central number. The automated system then calls two subscribers, at random, in the same area to confirm that water is running. Once verified, the system sends out a message to everyone in the service area, letting them know that water is available. As an incentive to participate in the program, first responders are given small payments.

Ari Olmos, a NextDrop project member and public policy graduate student at UC-Berkeley, said the prevalence of cell phones in Indian cities—1.2 wireless connections per person in urban areas, according to the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India—and a willing public sector make the country an ideal place for something like NextDrop.

“A service like this wouldn’t have worked five years ago,” he said, “but now there are so many phones in urban areas that the service seems feasible.”

In India, almost no city has a continuous water supply for all its residents, said Olmos, who worked with a micro-finance NGO in Peru before returning to school. Water is available from the taps for a few hours per day in some cities, or for a few days every week in others. Because access times vary, there is no way to know exactly when the water will be on. Thus, residents waste a lot of time waiting on water, with much of the burden placed on women and the poor.

Even the water boards do not know exactly where the water is, Olmos said. In the city where NextDrop operates, engineers set the operation schedule, but even they are in the dark about what is happening on the ground. Valve men go from neighborhood to neighborhood to turn the water supply on and off. If pressure is low, they might leave the water on longer to compensate. A bribe might also extend service beyond what was planned.

The UC-Berkeley group is learning how their system works through a pilot project that started last June in the southern city of Hubli. This location was selected because of prior connections through a team member’s research project, and also because it had a water board open to partnerships for improving service.

Olmos told Circle of Blue that Next Drop has already made one major change after the test run in Hubli—dropping the text messaging service and using an automated phone system instead.

“We came into the pilot expecting that people would be happy to participate with text messages,” he said, “because there was a perception that everybody used text messages. But, as it turned out, for a lot of the population we were working with, older people did not text as much as we thought.”

Additionally, Indian text messaging networks see a lot of spam, so the relevant information was getting lost in the noise, or even being ignored.

— Professor Tapan Parikh

University of California-Berkeley

For now, the Next Drop service is free for users, but Olmos said the six-member team is looking at functioning as a live-data service for the water board, in addition to generating revenue from selling subscriptions and advertisements—for example, soap companies would like to remind customers that it is a great time to wash when the water is on.

Initial funding—and the project itself—came from a class at UC-Berkeley on information technology (IT) and social development, taught by Tapan Parikh. The class divided into teams, each of which developed an IT project focused on social development. Olmos and his team members took the class when it was first offered in the fall of 2009 and won a prize grant of $5,000 from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

“The class is unique in its combination of information technology, social entrepreneurship, and international development,” Parikh said. Anyone at the university can pitch an idea to the class, even members of the San Francisco Bay Area community are welcome to nurture project ideas.

Olmos said current funding is sufficient to keep the pilot project running through August 2011. By then, the team hopes to prove that people are willing to participate in the service and can contribute accurate, timely information.

“If we can provide this data and cover the whole city, it would be helpful in providing transparency and accountability,” he said.

The Cloud on the Horizon

Transparency and accountability are the driving forces behind projects from several water NGOs that are looking to improve their own performance.

A new, strategic plan from one of the world’s leading water aid organizations, Denver-based Water for People, guarantees it will monitor projects for at least 10 years after completion.

“We felt, as an organization, that you can’t just say something is working,” said chief executive Ned Breslin in an interview with Circle of Blue. “You have to prove it. We said we can’t be sort-of-transparent.”

To that end, Water for People has developed a tool called field level operations watch, or FLOW for short. It uses open-source software, running Google’s Android operating system, and stores data using cloud-based computing—meaning that data is stored on web-based servers, known as the cloud. Because the information processing is not tied to one computer, data is instantly updated on FLOW and available for all to see once it is entered into a spreadsheet that is stored in the cloud.

— Ned Breslin

Water for People

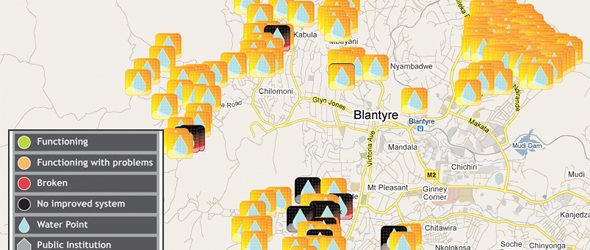

FLOW uses Google Maps and Google Earth to display the data and incorporates GPS coordinates for the water points, as well as pictures and video. Upon opening the map, an array of water droplets appears, which represent different Water for People projects. Clicking on a drop brings up a picture of the water source, its status— functioning, functioning with problems, broken, or no improved supply—when it was built, and when the data was last updated. Blank lines for data on water quality and quantity will be updated in the future.

The most immediate goal of FLOW is to show which projects are providing water and which are failing; an administrative bonus is to reduce the paperwork associated with project evaluation and allow for more sophisticated analysis.

“Traditional monitoring is a pain in the neck,” Breslin said. “Questionnaires have to be translated, you have boxes full of data that you need to analyze and input to a computer—that takes forever.”

With FLOW, Breslin can track how projects fare against each other over time, in addition to more rigorous district- and country-level analyses. And this is not idle work, either. Going through the paper-based reports has yielded big changes throughout the organization.

“If I look at the five years of data, every country program has one issue they’ve had to completely re-think based on monitoring,” he said.

But, Breslin said, the decision to post the organization’s every success and failure was not without disagreement among staff members. While the move was overwhelmingly endorsed, Water for People did lose some country-level staff, who worried that governments would not want to see failing results talked about so openly.

The next step for FLOW is to add hardware. Water for People is currently developing sensors to place in water pumps, and the plan is to test this year. If no water passes the sensor over the course of one day, it will send a signal to FLOW that something is amiss.

Other water NGOs also use data visualization and mapping to track projects. WaterAid, a London-based aid group, has used a form of its Water Point Mapper since 2002. At first, the tool relied on complex GIS software, but more recently it was overhauled to run on Excel and Google Earth.

Several governments in east Africa have adopted the mapping methodology to monitor the status of their water supply projects, said Mel Tompkins, a WaterAid press officer, in an email to Circle of Blue.

WaterAid is part of the H2.O Initiative, an umbrella organization with the goal of empowering water users by making data accessible to all. H2.O Initative is facilitated by United Nations-Habitat, with partners including Google, the School of Geo-information Science, and Earth Observation at the University of Twente (Netherlands), Water Services Trust Fund Kenya, WaterAid, and the German Society for International Cooperation.

The initiative was introduced during Stockholm Water Week in September 2010, but many of the tools are still in the development stage. Conceived as a way to collate data from disparate organizations and present it in visual formats, H2.O aims to assist decision-making by sharing data about individual projects—something not included in broad surveys like the UN’s Joint Monitoring Program for water and sanitation.

“There remain significant challenges in disclosing and sharing data,” said the UN-Habitat press office in an email to Circle of Blue, “which is also why this initiative is so relevant. Despite living in the supposed information age, organizations continue to relinquish their exclusive hold on data reluctantly. H2.O hopes to show that data is much more powerful shared than in hiding.”

The big questions, now, for the data mavens are how far their conviction will spread and how to ensure that the information they gather is accessible to all.

“We are looking to partner with organizations that are willing to change,” Professor Parikh said. “We hope that, over time, through competition or a diffusion of ideas, you would change the culture.”

But what about governments and monopolies? NextDrop seems to be working well in India, but the world’s largest democracy already has a public sector striving to improve its service—even going so far as to introduce citizen charters for each government agency, national to local, that spell out performance standards and how to redress grievances.

Parikh admits that getting governments to change may be the final, hardest step. “We haven’t bit that off yet.”

Brett Walton is a Seattle-based reporter for Circle of Blue. Contact Brett Walton

Note: Water for People’s chief executive, Ned Breslin, contributes blogs to Circle of Blue.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

We have been using not only IT but the peer review process for 6 years now to open up the water sector. Of course, to really open up the water sector it i not enough to just put the burden on the people in the field. We need to change the entire value chain.

The people in power and in the funding side have seen no real results (by results i mean a reduction in the water crisis) despite four decades of efforts. They need to look in the mirror to see their role in the sector’s performance. Its not governments only, the large fundraisers and intermediary NGOs, and institutions that are equally resistant to change.

We at PWX demand real accountability – since the project proposal is also present with original budget, the accountability is real compared to a simple water quality report. What was the original plan and what were results can been, including the decision (with peer review) to fund it. That is 100% transparency end-to-end.

So, the change of behavior has to happen in the North as in the South. The Peer Water Exchange has for 6 years tried to change behavior at both ends of the spectrum.

Interesting to see how very savvy marketing works in the sector compared to real long-term efforts to instill systemic change (collaboration, transparency, and efficiency to an sector plagued by lack of results.