Water Rights Transfers and High-Tech Power Plants Hold off Energy-Water Clash in Northern China

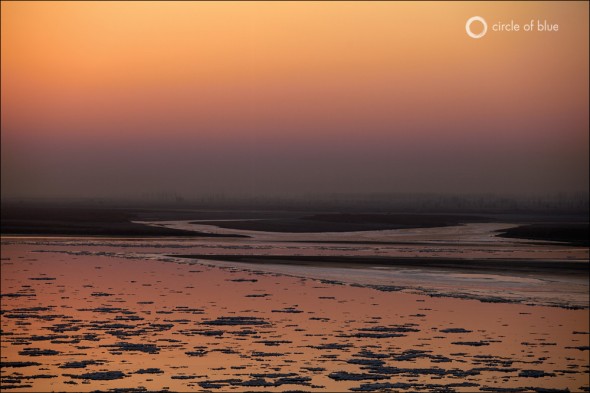

Along the Yellow River, China acts on looming crisis with ambitious water conservation and transfer program

By Nadya Ivanova

Circle of Blue

YINCHUAN, China—On Sept. 7, 2007, during a morning briefing in Beijing on China’s newest five-year strategy for supplying the nation’s soaring demand for energy, Hu Weiping described a characteristically Chinese response. Hu, a veteran of China’s powerful National Development and Reform Commission and a top executive in its newly established National Energy Administration, told a group of academics and journalists that the nation’s top energy priority was to construct what he called “energy bases” for “orderly development of coal and optimizing the construction of coal-fired power generation.”

Translation: China wanted to consolidate its primary energy-producing sector, building coal-to-chemical refineries and coal-fired power plants in closer proximity to coal mines.

Hu said the enormous new coal production and processing bases—each of which would encompass hundreds of square kilometers and cost about $US 30 billion to build—would be located in six provinces, four of them in arid northern China, where most of the country’s coal reserves lie.

Almost four years later, on a flat and desolate expanse of alkaline desert near Yinchuan, the provincial capital of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, one of the coal bases that Hu described is rapidly taking shape. The Ningdong Energy and Heavy Chemical Industry Base is a bustling Lego set of energy infrastructure. Bulldozers, workers, and cranes snap together standardized parts, churning out colossal cooling towers, candy-striped chimneys, and stick-figure transmission towers and lines for the world’s most advanced coal-fired power plants, coal-to-chemical refineries, and coal mines.

The phalanx of energy installations, with mines and roads spanning nearly 3,500 square kilometers, takes advantage of two vital resources: a coal reserve underneath the base—China’s sixth largest reserve, conservatively estimated to contain 27 billion metric tons—and a ready source of water in the Yellow River, conveniently located 35 kilometers away.

The Ningdong Energy Base illustrates China’s capacity to fuel the fastest growing industrial economy in the world, while also contending with national anxiety about northern China’s steadily diminishing freshwater supplies that are needed to mine, process, and use the region’s coal.

In late December 2010, for instance, the Huadian Power International Corporation—one of China’s largest electricity producers—opened a state-of-the-art, 1000-megawatt, supercritical, air-cooled coal-burning unit at the Lingwu Power Plant in the Ningdong Energy Base. The station—the first of its kind in the world—will use 9,000 cubic meters (2.4 million gallons) of water a day for industrial operations and cooling. A similarly sized conventional coal-fired plant would use 44,660 cubic meters (11.8 million gallons) of water daily, or nearly five times as much, according to an investment stock statement issued by the company.

Workers, Watts, and Water: A Developing Industrial Base

When the Ningdong Energy Base is completed in 2020, its full complement of mines, along with 20 power plants and coal-to-chemical facilities, are expected to employ 20,000 workers, provide 20,000 megawatts of electrical generating capacity, manufacture millions of tons of chemicals and produce more than 200 million metric tons of coal a year. This is equivalent to the electrical generating capacity today in Michigan, nearly the same chemical manufacturing as occurs between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Louisiana on the Mississippi River, and the amount of coal that is mined each year in Kentucky, Montana, Pennsylvania, and Ohio combined.

In effect, the Ningdong Energy Base is setting globally significant standards of industrial performance that are vital to China’s modernization.

The base is also the focus of new policy and practices designed to conserve water. According to its builders—among them Shenhua Group, the world’s largest coal company—Ningdong will eventually use 100 million cubic meters (26.4 billion gallons) of water annually. Though the mines will recycle 100 percent of the water needed to process coal, and the power plants will recycle more than 95 percent of the water used for operations, that’s still a lot of water in a dry, expanding, food-producing province that is limited by a 1987 law. The law states that no more than 4 billion cubic meters (10 trillion gallons) can be withdrawn annually from the Yellow River for all uses by Ningxia’s farmlands, cities, and businesses.

Ningxia’s Unexpected Boom

A small and poor northwestern province known for its wolfberries, rice, and wool, Ningxia seems an unlikely magnet for such development and reform. Much of the province is a moonscape of desert and alkali flats where nothing organic can grow.

But since 2000, when China launched the “Go West” program to encourage industrial development and job growth in 11 western provinces and autonomous regions, Ningxia’s income levels have been steadily rising.

In the last five years, Ningxia’s economy has grown by more than 100 percent, while its energy production and the value added by industry more than doubled. The production and consumption spikes have turned the province from a primarily agricultural society to one that is putting more attention on developing heavy industry and tapping enormous coal reserves, which supply 99 percent of its energy.

The Ningdong Energy Base—where construction started in 2003, the same year that a pilot water-trading program was launched in Ningxia and Inner Mongolia—is central to the province’s economic turnaround. The new wealth is visible 50 kilometers (30 miles) away in the provincial capitol of Yinchuan, which has grown from a small urban hodgepodge of three-story buildings to a city of concrete high-rise apartments and offices, eight-lane boulevards, and fresh road stripes. Parts of the city are so new that sidewalk tiles still have the labels from the packaging boxes.

The economic restructuring, though, is pressuring Ningxia’s limited water supply on a scale never seen here. The province’s lifeline is the Yellow River, which drains a region that receives a mere 300 millimeters (12 inches) of rain annually. And last year, total water resources in Ningxia were 35 percent less than in 2000.

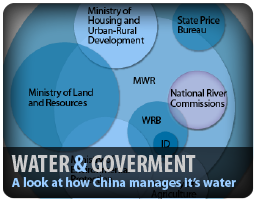

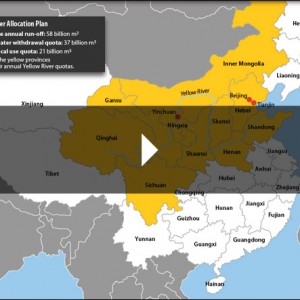

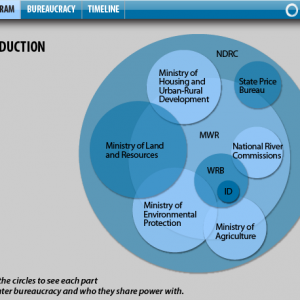

Under a 1987 plan enforced by the Yellow River Conservancy Commission (YRCC), which oversees the basin, Ningxia and the other Yellow River provinces are bound by an annual water allotment that serves industrial, agricultural, residential, and ecological needs for 140 million people and 15 percent of China’s irrigated lands. The YRCC controls this allocation with an extensive network of remote monitoring stations and sluice gates.

The 1987 plan to allocate and enforce specific allotments of water to each of the 9 provinces in the Yellow River Basin is based on an estimated river volume of 58 billion cubic meters (15 trillion gallons). This estimate, however, has proven faulty: last year, the river volume fell to 53 billion cubic meters (14 trillion gallons), and, in 2003, it dropped below 45 billion (12 trillion gallons). Though enforcement has reduced inter-provincial water disputes and made it possible for the Yellow River to reach the sea—something it did not do in the 1990s—water levels in the river are low.

Agriculture uses about 93 percent of Ningxia’s water resources, or roughly 3.4 billion cubic meters (900 billion gallons). But, by the end of the decade, agricultural water use is projected to drop to 78 percent in order to provide more water to cities and to coal production, coal combustion, and coal-based chemicals.

In short, there isn’t really enough water to go around, but the cities, industries, and farmers make do with what they have.

“The current water allocation of 4 billion cubic meters (1 trillion gallons) for Ningxia cannot satisfy the needs of agriculture, let alone the whole province,” said Sun Xueping from the Irrigation Bureau at Ningxia’s Water Resources Department. “The limited water resources have always been the bottleneck of the economic development in Ningxia.”

Farms to Factories: Water Efficiency Upgrades Transfer and Conserve Water

An ambitious water conservation and transfer program, started in 2003, is helping Ningxia hold off the looming confrontation between its scarce water reserves and growing coal-based industrial sector.

The pilot program, known as “water rights trading,” requires new industries to invest in lining and repairing irrigation canals in exchange for the right to use Yellow River water. The upgrade annually saves millions of cubic meters (billions of gallons) of agricultural water that then get transferred to power plants in the region.

In Ningxia, the program started with the launch of the Ningdong Energy Base. Today, it is the only way new power facilities can get approval to operate. A similar program has been operating in Inner Mongolia, the largest coal-producer in China.

Since 2005, Ningxia and Inner Mongolia have collectively saved about 330 million cubic meters (87 billion gallons) of water, according to the YRCC. That’s enough water to begin tapping some of the big, new coal reserves in the arid north—which China needs to fuel its growth—as well as to operate the Ningdong Energy Base and others like it in northern China.

“The project can supply electricity, help develop the local economy, and raise people’s living standard. But it could also damage the scarce water resources, exacerbate desertification, and cause pollution,” said Wang Lifu, vice dean of the Development and Programming Department at Ningxia’s Development and Reform Commission, in an interview with Circle of Blue. “These are the trade-offs that we are considering. If we plan well, we can contribute to the local areas. But the plan is standing on thin ice. There are still many uncertainties in the future—the ecology, the water scarcity problem.”

The changes occurring in water rights in the north are seen by government and industry leaders as essential to solving some of the critical water stresses in northern China, where unclear water rights and low water fees have led to decades of rampant overuse, leaving the Yellow River so depleted it once ran dry for hundreds of kilometers short of its delta at the Bohai Sea.

Chronic water shortages and growing conflicts over supply generated the political momentum for the pilot water transfer programs now sanctioned by both the Ministry of Water Resources and the YRCC in Ningxia and Inner Mongolia.

How Trading Works

The solution, Ningxia experts say, is to transfer water from agriculture to industry by investing in water-saving irrigation. The first three projects under the water trading program remodeled more than 60 kilometers (37 miles) of centuries-old canals and about 170 kilometers (105 miles) of substreams, along with rebuilding more than 2,500 ancillary buildings in Ningxia, which freed up 50 million cubic meters (13 billion gallons) of water a year for coal-fired power plants at the Ningdong Energy Base and elsewhere.

“Those who use the water are the ones who pay for it. That’s the principle,” said Wang Dong, deputy director of Ningxia’s Department of Water Resources Governance, the local agency responsible for examining and approving the applications for the program.

The water transfer program is viewed as a lifesaver for many new facilities, which generally are unable to secure a direct Yellow River water quota. New industries in Ningxia, as a result, scramble for water from the trading program that comes at a hefty price of $US 0.80 to $US 0.86 per cubic meter.

But the application and acceptance standards to participate in the program are high.

Polluting and water-intensive industries cannot apply, and many have been forced to restructure to use less water. Since 2005, provincial authorities have shut down around 60 paper mills, along with a number of small power plants and fertilizing companies.

Other industries are forced to restructure their operations in a way that uses less water. Out of the 30 to 40 companies that have applied to trade water in Ningxia since 2004, only seven have been approved by the YRCC.

“The current policy in Ningxia is that we build industry based on the water available, not the other way around,” said Zhang Yuan, director of the Ningxia Tanglai Canal Management Department, one of the province’s irrigation districts.

No Water, No Permit

The directive to secure water prior to construction has taken firm hold in all of northern China’s provinces, and especially here in Ningxia.

Last month, Shenhua and its South African partner Sasol announced they were pulling out of a plan to build a coal-to-liquids plant—capable of producing 94,000 barrels of transportation fuels a day—at the Ningdong Energy Base. The companies have been unable to gain approval for an $US 8 billion to $US 10 billion plant from China’s National Development and Reform Commission, the economic management agency.

In interviews with Circle of Blue, government and academic authorities said the NDRC’s reluctance to approve the plant is due in large part to its huge thirst for water. If built, the plant would use 152,000 cubic meters (40 million gallons) of water a day and would be one of the largest industrial users of water in the nation. (An upcoming article in this Choke Point: China series will report on China’s troubled coal conversion program.)

Authorities said that was too much water for one facility seeking water trading rights— which is a strong signal that the pilot program is working.

“I think that, if carried out properly, water rights trading should eventually improve the efficiency in a more cost-effective way, said Ma Jun, author and director of China’s Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs. “We have seen some successful models, successful stories. But, in general, it hasn’t been carried out in a big way, in a widespread way. So it remains to be these pilot types of projects.”

A Nation Hampered By Water Scarcity

Tight freshwater supplies are nothing new in China, where 80 percent of the rainfall and snowmelt occurs in the south, while less than 20 percent of the water is in the north and west, where most of China’s energy reserves, industry, and people are concentrated. China’s sizzling economic growth is prompting the expanding industrial sector—which consumes 70 percent of the nation’s energy—to tap new energy supplies, particularly the enormous reserves of coal in the dry north.

Though national conservation policies have helped to limit increases, water use nevertheless climbed to a record 599 billion cubic meters (158 trillion gallons) in 2010, which is 50 billion cubic meters (about 13 trillion gallons) more than in 2000. Over the next decade, according to government projections, China’s water use will reach 620 to 630 billion cubic meters (nearly 165 trillion gallons) annually, and an announcement earlier this year by the government indicates water use could reach as high as 670 billion cubic meters (177 trillion gallons) annually over the next decade.

Meanwhile, China’s total water resource, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, dropped 13 percent between 2000 and 2009, from 2.77 to 2.42 trillion cubic meters (740 to 730 trillion gallons). Last year, however, total water reserves surged to 2.85 trillion cubic meters (740 trillion gallons), the highest since 2002, largely as a result, said authorities, of persistent flooding in parts of southern China.

The northern provinces, though, are getting drier, prompting China to undertake an array of policy and infrastructure responses. The country will invest $US 62 billion to build the South-North Water Transfer project, a 3,000-kilometer web of canals and tunnels that, when completed sometime in the next two or three decades, will divert nearly 40 billion cubic meters (10.5 trillion gallons) annually from the south to thirsty provinces in the north. China is also considering shipping massive amounts of desalinated water from the Bohai Sea in the east to supply eastern Inner Mongolia’s coal reserves that can’t currently be tapped because there is not enough water.

China has also taken millions of hectares of farmland out of production and relocated water-wasting eastern industries to the coast. Meanwhile, big cities like Beijing are investing billions of yuan into retrofitting their sewage treatment systems to recycle wastewater.

New Technologies in the West

Water conservation is the tool that, so far, has made it possible for China to develop and evade a water crisis. Since the 1990s, through a combination of carrots and sticks, the central government has required industries and coal-fired power plants to prove new construction sites had sufficient water to operate and that new coal installations met water recycling standards.

Here in Ningxia, new industries that take water from agriculture are required to install technologies that burn coal more efficiently, use less water, and vent less sulfur into the atmosphere.

There are tradeoffs that China expects companies to live with.

The new air-cooled power stations under construction at the Ningdong Energy Base are more expensive to build and operate than conventional water-cooled plants. That’s because air-cooling saps more energy from the plant than a wet-cooled evaporation tower. The government ordered its state-owned companies to develop the technology and build the plants to comply with the country’s new desire to develop in a way that is more environmentally sensitive.

“While we want to continue developing the economy, we also have to hold up the highly polluting and water-intensive industries. That’s why we have created restrictions,” said Si Jianning, deputy director of the Water Saving Office at Ningxia’s Water Resources Department. “Many projects in Ningdong have to use a dry cooling system, even if it means that they have to invest $US 46 million to $US 61 million to install it to save water.”

Nadya Ivanova—who has reported from China, Europe, and the United States—is a Chicago-based reporter and producer for Circle of Blue. Reach her at circleofblue.org/contact. Aaron Jaffe, a Chicago-based reporter and photographer for Circle of Blue, and Wang Zhuo, a Beijing-based research assistant, contributed reporting. Reach Jaffe at circleofblue.org/contact.

Contributions by Keith Schneider, Traverse City-based senior editor for Circle of Blue, and Jennifer Turner, Washington, D.C.-based director of the China Environment Forum at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Contact Keith Schneider

Research assistance by the School of Civil and Water Conservancy Engineering, Ningxia University.

Map and graphic by Stephanie Stamm, Justin Manning, Stephanie Meredith, and Kate Roesch, undergraduate students at Ball State University.

Connor Bebb assists in daily operations, aids in research, oversees social media outlets and develops social media strategies at Circle of Blue.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!