Peter Gleick: Playing God

In a desperate attempt to make it easier to solve California’s complex and contentious water problems, a dangerous new idea has recently been floated — intentionally letting some species go extinct rather than take the difficult steps needed to save them and their ecosystems. This idea should be quashed, smothered, strangled, and quickly tossed in the dumpster of failed ideas.

The first hint of this appeared earlier in February in the 52-page study released by the Delta Stewardship Council. That report argued that it was possible that some species of fish might be so devastated already and their ecosystems so ruined that they were unlikely to survive even with significant efforts to save them. This, of course, is an argument long made in private by some agricultural and urban interests unwilling to accept the difficult strategies to save endangered and threatened species because it might cost them water.

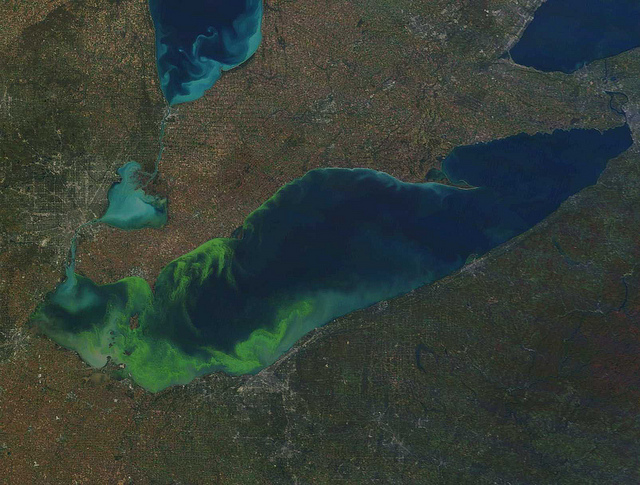

Then, just this week, the argument for explicitly permitting extinction was described in the newly released water report from the Public Policy Institute of California. They are stunningly blunt, calling for the state to consider practicing “endangered species triage,” intentionally permitting a species to go extinct if an argument can be made that it will somehow help other species survive — a very strange concept to ecologists who look at the health of overall systems. This is, however, not really an argument about letting one species die off to save other species: their argument hides the real driver behind the destruction of fisheries and aquatic ecosystems — economic competition for water. Any species can be saved if we are willing to spend the money and put in place the policies to do so — such efforts just come at an economic cost. PPIC acknowledges this driver deep in their report (on page 412) when they say: “The condition of native fish populations has continued to deteriorate, despite decades of well-intentioned but insufficient and poorly coordinated policies to protect them. Efforts to stop these declines now threaten the reliability of water supplies and flood management projects.”

That’s the real point: now that serious efforts are finally being made to tackle the real threats driving Delta fish species to extinction, economic interests are being threatened and fighting back. The delta smelt is not being driven to extinction by conflicting priorities among other species of threatened fish. It is being driven to extinction by policies around human withdrawals and uses of water for economic gain. The idea of endangered species “triage” is simply a wedge in the door to permit species to go extinct when the policies to protect them cause hardship for special interests.

There are those who believe that killing off a species of animal, or bird, or fish in the name of economic gain is reasonable, including legislators trying to weaken or destroy the Endangered Species Act. To me this is a moral, ethical, and political outrage. Moreover, it is a infinitely dangerous idea, since once we start down that road, where do we stop? Who gets to play God? If condemning the delta smelt or coho salmon to extinction in return for a few hundred thousand acre-feet of water to grow alfalfa, or cotton, or almonds is acceptable or to permit more housing in floodplains, why not wipe out the San Joaquin kit fox and the California clapper rail in order to have more development on sensitive lands in the Central Valley and along the edges of San Francisco Bay? And why stop there? If economics rules, then those sperm whales still have lots of great oil in them and killing the last tuna for sushi is just a financial decision.

Endangered species triage? That way madness lies, with no end except spiraling ecological destruction, impoverishment of the environment, a sterile landscape, and the final triumph of money over our souls.

Peter Gleick

Perhaps more to the point, who should be making the distinctions on which species we value? In the politically charged atmosphere in which California water supply decisions are made, could we anticipate the fate of any decision making body charged with the role of determining those species worthy of continued existence? We have a history of denial and fighting over the conclusions reached by CDFG & USFWS for the management of the Delta. What framework would be suitable for making these new determinations?

With more 85% of our water going to agricultural irrigation and another 40 to 50% of urban demand for landscaping, it seems obvious that conservation and reclamation are the low hanging fruits. Continued investments in demand management are needed. Irrigation efficiencies are too low. Our benchmark of 20% reduction has insufficient basis when we broaden our view to identify the possibilities of optimal water use.