South of the Border—Second Environmental Review of Tar Sands Pipeline Leaves Many Groups Unsatisfied

Residents and lawmakers in Nebraska mull their options for protecting key groundwater sources.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

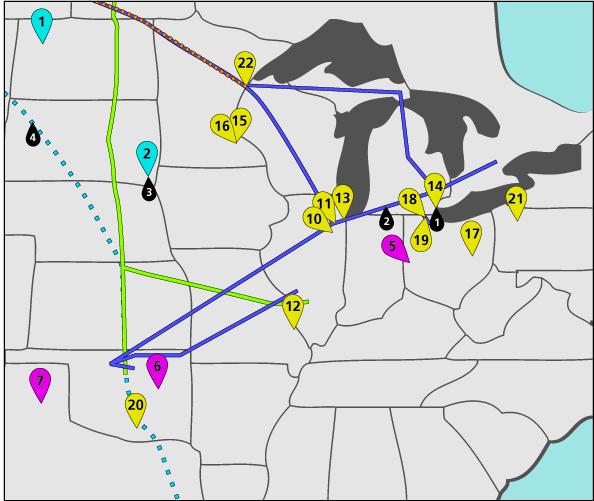

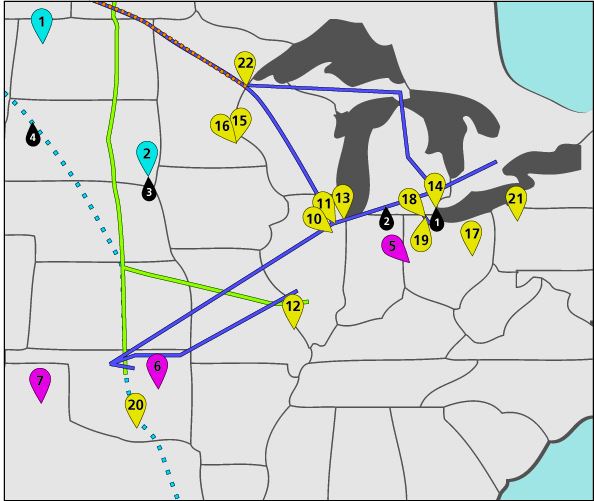

On April 22, the U.S. State Department released a supplemental environmental review for a proposed pipeline that would funnel 700,000 barrels of oil per day 2,750 kilometers (1,710 miles) from Canada’s tar sands to refineries on the Gulf Coast of Texas. The department completed the supplemental review after its initial draft, released in April 2010, was given the lowest possible rating of “inadequate” by the Environmental Protection Agency.

In the year since, U.S. senators, state representatives, and various national, state, and local interest groups also have requested a more detailed review of the safety of the Keystone XL pipeline and its effects on land use and water resources. The route proposed by TransCanada, the project developer, cuts across the High Plains Aquifer System, one of the world’s largest aquifers and the water source for 2.8 million people and nearly 5.3 million hectares (13 million acres) of irrigated farmland.

— Senator Mike Johanns,

R-Nebraska

However, the supplemental environmental impact statement (EIS) has not alleviated those concerns, especially in Nebraska where the $US 7 billion pipeline would cross two primary units of the High Plains Aquifer—the Ogallala and the Sand Hills.

In a written statement, Nebraska’s Republican Senator Mike Johanns questioned the conclusions in the supplemental EIS.

“I was pleased that the State Department issued a supplemental EIS, which I had requested months ago,” Johanns wrote to Circle of Blue. “There is still much to review in the document, but the bottom line is that the State Department’s position doesn’t seem to have changed much. The State Department still thinks the best route goes through the Sand Hills, and I think that’s wrong.”

Though the supplement incorporates minor changes to the location of storage tanks and the intensity of pumping pressure, the new information “does not alter the conclusions reached in the draft EIS regarding the need for and the potential impacts of the proposed project,” according to the State Department’s supplemental EIS.

The State Department is the permitting agency because the pipeline crosses international boundaries. The department has already approved two pipelines from the tar sands to refineries in the U.S., both originating in Hardisty, Alberta. The 992-mile Alberta Clipper line ends at Superior, Wisconsin. The 1,600-kilometer (2,151-mile) Keystone line has terminals in Illinois and Oklahoma. The combined capacity is 1.4 million barrels per day, but the U.S. currently only imports 1.1 million barrels a day from the tar sands.

Potential for Pollution

The areas of greatest concern for water resources—pipeline spills and the location of the proposed route—seem to have been given superficial treatment, said Susan Casey-Lefkowitz, the international director for the Natural Resources Defense Council and a tar sands specialist.

“My feeling is that, rather than really going into detail in areas and fleshing them out, they spent a lot of time and pages explaining why they didn’t need to go more in-depth,” Casey-Lefkowitz told Circle of Blue. She continued, saying that the State Department “seems to take the stance that an accident or spill is unlikely, so we don’t need to worry.”

But when it comes to unlikely accidents linked to energy sector, there are two striking examples over the last year: the Deepwater Horizon blowout in the Gulf of Mexico and the Fukushima partial meltdown in Japan. And, lest it be overshadowed by those monumental bookends, last June there was a spill from a pipeline carrying tar sands oil in southwestern Michigan, where more than 800,000 gallons of oil flowed into a tributary of the Kalamazoo River from a pipeline owned by Enbridge, a Canadian company.

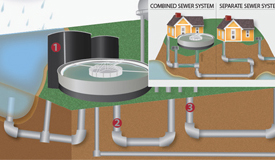

To understand the potential for a pipeline spill, the physical properties of tar sands oil are important.

The Keystone XL pipeline—like the Enbridge pipeline—will carry diluted bitumen, which is a substance that contains more hard particles than conventional crude, and thus requires higher pumping pressures within the pipeline. This makes the oil more corrosive and more likely to trigger a spill, said Casey-Lefkowitz, who cited an NRDC study of similar pipelines in Alberta, Canada, where spills from internal corrosion were 16 times more likely.

In light of the potential for spills, the decision on where to site Keystone XL is paramount.

Location, Location, Location: Who decides?

Opposition to the pipeline has been fiercest in Texas and especially in Nebraska, where the proposed route crosses two main units of the High Plains Aquifer. The aquifer system covers eight states, but Nebraska has the highest share of the aquifer’s land area and is also the primary water user. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, Nebraska accounted for 45 percent of the acreage irrigated by the aquifer in 2002.

Nebraska’s lawmakers have been thrown into some confusion by a leaked memo from the Congressional Research Service, the government agency that does research for members of Congress. Requested by Representative Lee Terry, a Republican from Nebraksa’s second district, the memo describes federal laws related to pipeline permitting and safety.

While the federal government has legal authority for siting natural gas pipelines, no such authority exists for oil pipelines, leading the memo’s authors to write that “state laws establish the primary siting authority for oil pipelines.”

Because CRS works exclusively for Congress, the memo’s authors were not allowed to speak with Circle of Blue, a CRS press official said.

–Susan Casey-Lefkowitz,

Tar Sands Specialist, NRDC

Terry shared the memo—dated September 30, 2010—with some state legislators, and it was made public on March 30, according to the Omaha World-Herald.

If the Keystone XL pipeline were approved, TransCanada would automatically have the authority in Nebraska to use eminent domain to secure land for the pipeline right-of-way. Unlike Montana and South Dakota, Nebraska does not have laws that allow the state to regulate the location of oil pipelines, and the CRS memo suggests that authority for approving the pipeline’s route actually rests with the states themselves.

Several Nebraska lawmakers are now scrambling to make sure they have that power. State Senator Annette Dubas has submitted a bill to require oil companies to file information on pipeline routes with the state’s Public Service Commission, which would then have the authority to approve the pipeline application before eminent domain could be invoked.

Dubas’ bill is one of three sitting in the Natural Resources Committee that would give the state some measure of control over oil pipelines—though all face an uphill struggle. Joselyn Luedtke, a legislative aide, told Circle of Blue that Dubas’ bill does not have the votes to get out of committee.

To ensure broad participation, many parties have proposed extending the comment period and holding field hearings in the affected states. A coalition of 32 groups—including the Sierra Club, the Nebraska Farm Union, the National Wildlife Federation, and the Natural Resources Defense Council—wrote a letter to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton requesting the comment period be extended from 45 days to 120 days. The State Department has not indicated whether it will consider doing so.

Though the department seems intent on keeping the permitting process move along, whether TransCanada is ultimately given permission to build the pipeline is still unsettled, Casey-Lefkowitz said.

“I think there are different voices within the administration,” she said. “Some who want to see any mechanism for additional oil supply built, and some who are concerned about climate change and pipeline safety, and whether it undermines clean energy initiatives the administration is taking. We’re very much seeing a process where a decision has not been made and where you have voices on all sides.”

Source: Omaha World-Herald

Brett Walton is a Seattle-based reporter for Circle of Blue. Contact Brett Walton

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!