St. Louis Sewer District and U.S. Justice Department Reach Record $4.7 Billion Clean Water Act Settlement

The sewer district joins more than 40 American municipalities renovating their sewer systems to comply with the CWA.

The Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District, the nation’s fourth-largest system, will overhaul its sewer infrastructure at an estimated cost of $US 4.7 billion over 23 years, according to a settlement announced on Thursday by the U.S. Justice Department and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

It is the largest municipal Clean Water Act settlement in U.S. history, according to the EPA.

The sewer district, which serves the city and parts of two counties, will build three storage tunnels and increase capacity at two of its seven treatment plants. These improvements are expected to eliminate 49 million cubic meters (13 billion gallons) of untreated sewage, otherwise discharged illegally each year from the district’s 15,500-kilometer (9,600-mile) network of pipes.

“The people of St. Louis, including those who live in minority and low-income communities, will receive tangible, lasting benefits from this significant settlement,” said Ignacia Moreno, Assistant Attorney General for the Justice Department’s Environment and Natural Resources Division, in a statement.

The agreement also includes a provision that the sewer district spend at least US$ 100 million on green infrastructure in low-income or minority areas that have traditionally borne the brunt of polluted water and air.

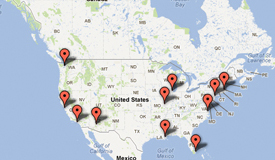

Reducing the amount of raw sewage and contaminated storm water dumped into the nation’s rivers and streams is a priority area for the EPA. Since 1998, more than 40 municipalities — including Atlanta, Baltimore, Indianapolis, Los Angeles, Louisville, and San Diego — have reached similar settlements with the federal government. These settlements mandated, among other things, sewer improvements estimated to cost a large city anywhere from hundreds of millions to billions of dollars.

And some of the largest settlements have come in just the last few years. In December, for example, the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District, which serves the Cleveland area, agreed to a plan for US$ 3 billion in system improvements to keep untreated sewage out of Lake Erie. And 15 months ago, Kansas City, Missouri, agreed to pay US$ 2.5 billion in renovations to its sewer system.

In many cities, all wastewater — street runoff, toilet flushes, and commercial operations — flows into the same set of pipes. These ‘combined sewers’, as they are called, often exceed the treatment capacity at wastewater plants during storms or other high-flow periods, resulting in the surplus of sewage being spilled into rivers, still untreated. Separating these systems and increasing treatment capacity has been quite expensive.

The Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District has invested US$ 2.3 billion over the last 20 years to reduce both combined and sanitary sewer overflows, but the city does not dispute that it needs to invest even more. And the burden of payment will likely fall on its citizens in rate increases.

The agreement is fair, the sewer district said in a statement, but “the fact remains that this is billions of dollars that will come from the pocketbook of St. Louis ratepayers — with little-to-no state or federal assistance — and will be unavailable for other critical needs in our community.”

Because the sewer district is under a federal gag order, the statement is the only comment it can make at this time.

Note: This article has been corrected to clarify that the Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District serves not just the city of St. Louis, but parts of the surrounding counties.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

The problem with the article is that it keeps referring to “the city,” not realizing that MSD serves St. Louis city, St. Louis county, and portions of northern Jefferson County — all separate political entities.

Thank you for your comment. We have corrected this article to clarify that the Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District serves not just the city of St. Louis, but parts of the surrounding counties.

Really somebody with some authority should take some time and learn what sewage is, how it impacts open waters and how it can and should be treated. There was nothing wrong with the Clean Water Act, but the trouble started when EPA set sewage treatment standards and used an essential test (developed in 1920) incorrectly and as one of its many negative consequences, ignored 60% of the pollution in sewage Congress intended to ‘treat”. Among this waste, nitrogenous (urine and protein) waste, which besides exerting an oxygen demand (just like fecal waste) also is a fertilizer for algae, thus contributes to eutrophication often resulting in dead zones, now experienced in all open water bodies.

Amazingly EPA, parroted by States, environmental groups and the media, now blames the runoffs from farms and cities for this same type of pollution, it now calls ‘nutrients’.

Of course we also should not forget that most old cities have combined (sewage and storm water) sewage collection systems, which do have CSO’s (Combined Sewer Overflows) in case the flow rates in such a system exceeds 3 to 5 times the average daily flow (the sanitary sewage), due to extremely large rain storms. Newer cities have separate sewage collection systems, where the supposed to be clean storm water is discharged directly into a river. Decades later we now realize that this storm water is not clean and probably also needs treatment. Still there has not been an objective engineering analysis comparing the two system not only on cost, but more important on their benefits towards cleaner water. When all the cards are on the table, one has to come to the conclusion that combined systems not only are cheaper to construct, but also much better for the environment.

However, in light of the fact that nitrogenous waste is sewage is still not required to be treated, all these studies will be worthless and not improve our open waters. And since this is only caused by the fact that those in charge refuse to acknowledge EPA’s failure to implement the CWA, due to a faulty applied test, we only can expect more failure of this second largest federally funded public works project.