Provincial Differences: Green Hunan and Dry Gansu

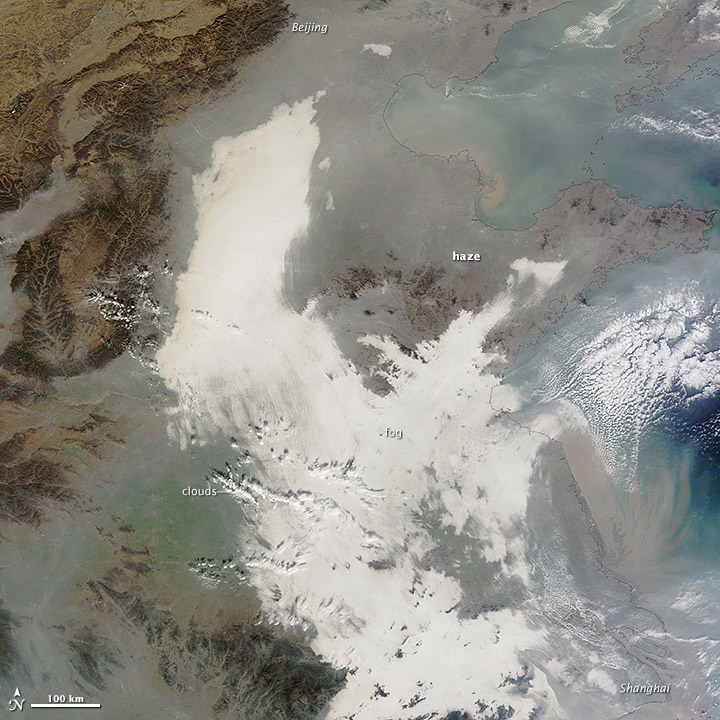

Circle of Blue reporter Nadya Ivanova starts her second of three weeks reporting in the field from China, where she wonders about the effects of regional development and pollution on farming practices.

CHANGSHA, China — Even through the thick fog and fine drizzle that veil Changsha’s clusters of new concrete high-rises, the city’s streets bathe in lush green and bright spring blossoms. It’s the rain season here in the capital of Hunan Province in central China. The air is sticky and damp, and the soil is soaked with water. It’s been pouring so much lately that locals joke it has only rained twice this year — the first time for three months straight and the second for two months on end.

Much of this Chinese city of 7 million was rice paddies 20 years ago. Banking on the province’s abundant natural resources, Changsha has grown so much in the last decade that it is now about to open a subway system. It is urbanizing so fast that city planners have to revise their five-year plans every year to catch up with the whirlwind development. More and more heavy metal factories are now opening up on long stretches of the nearby Xiangjiang River, a tributary of the Yangtze River.

I am here to conduct research for the next Choke Point: China report, as a follow-up to the first project by Circle of Blue and the China Environment Forum last year.

Apart from Hunan, my trip takes me to western and eastern China, to understand more about this nation’s confrontation between diminishing freshwater reserves and rising demand for grain and energy. I am in China along with my colleague Keith Schneider, who’s touring the central, northeast, coastal, and southwest regions of the country.

Though Hunan – known for its hot temper, spicy food, revolutionary past – is now swimming in water, drought is a not so distant memory.

Just a year ago, the province was in the grips of a prolonged dry spell that affected 35 million people across five eastern and central Chinese provinces, leaving 3.5 million with limited access to drinking water, suspending cargo shipping, and exacerbating power shortages at the beginning of the peak summer season.

As Circle of Blue reported in 2011, droughts and water shortages across China are now occurring with such frequency that they are putting the nation’s farm productivity and energy generation at risk, as modernization demands and global commodity prices are steadily increasing.

While an exception in places like Hunan, dry weather is the norm in Gansu Province, which I visited last week.

In this arid corner of northwestern China, small plots of maize and wheat squeeze between barren hills that are as dry as desert slopes. Rice paddies dot the banks of the Yellow River and its tributaries, a real lifeline here. Seen from above, the farms look like little oases surrounded by a wasteland.

Like Hunan, this poor province is changing rapidly.

Since 2000, when China launched the “Go West” program to encourage industrial development and job growth in 11 western provinces and autonomous regions, Gansu’s industries and income levels have been steadily rising. The development has turned the province from a primarily agricultural society to one that is putting more attention on developing a heavy industry.

Seen on the surface, green Hunan and dry Gansu could not be more different. But look closer into their fast transformation, and you cannot help but wonder – as China moves its development west to places like Hunan and Gansu, will it transfer its pollution as well?

Nadya Ivanova,

Circle of Blue reporter

, a Bulgaria native, is a Chicago-based reporter for Circle of Blue. She co-writes The Stream, a daily digest of international water news trends.

Interests: Europe, China, Environmental Policy, International Security.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!