Forecasting Western U.S. Water Supply in 2012: La Niña Again Delivers a Wet North and a Dry South

As water availability data starts coming in, this year’s water allocations and the potential consequences for irrigation, hydropower, wildfires, and flooding are being assessed — La Niña weather patterns have returned this year, but water supply conditions generally are not as extreme as they were 2011.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Though the Gregorian calendar marks the vernal transition a few weeks earlier, the month of April signals the end of winter for water watchers in the western United States — and with the changing seasons comes a subsequent decline in the snowpack that fills the region’s rivers and reservoirs.

As knowledge about water availability for the coming spring and summer becomes clearer, this is the time of year that resource managers set water allocations and assess the potential consequences for irrigation, hydropower, wildfires, and flooding.

From the Sierra Nevada to the Rockies, the snow that built up during the winter months is now melting faster than it accumulates — if it is still accumulating at all. Many basins in Arizona and New Mexico have already melted out.

“If we don’t have maximum snowpack by now, we’re not going to get it,” said Jan Curtis, a climatologist with the National Water and Climate Center in Portland, Oregon.

Another La Niña

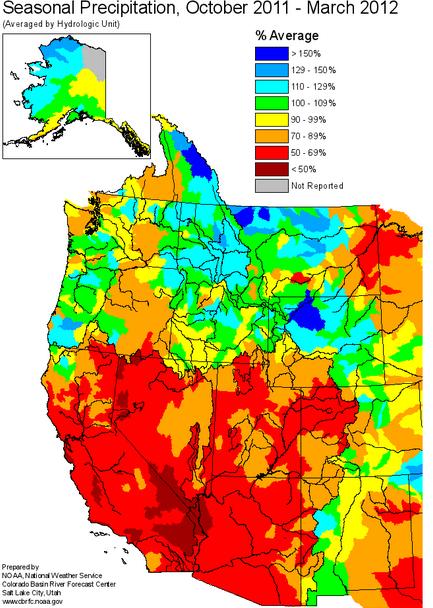

Historically speaking, some river basins barely moved the hydrograph this winter. Streamflow forecasts from the National Water and Climate Center show average to above-average flows in the northern Rockies and the Cascades, but conditions well below normal in the rest of the American West. Maps showing precipitation from October 2011 to March 2012 confirm the distribution.

Like the winter of 2010-2011, La Niña conditions again dictated weather patterns this year. La Niña is a cyclical cooling of the surface waters in the eastern Pacific Ocean, a phenomenon which brings wetter conditions to the Pacific Northwest and northern Rockies but drier weather to the Southwest.

However, not all La Niñas are the same, Curtis told Circle of Blue. Parts of New Mexico had an unusually rainy autumn, and the winter months were much warmer and drier in the upper Missouri River Basin.

In other words, it is unlikely that states in the upper Midwest will see a repeat of the historic floods of 2011, when a deep snowpack in the northern Rockies and heavy spring rains swelled the Missouri River to more than twice its record flow. As of April 1, the Army Corps of Engineers, which manages dams on the Missouri, is predicting an annual runoff that is slightly lower than normal.

Water Supply: Up on Colorado, Down on Rio Grande

Despite the consecutive La Niña periods, many water providers are not feeling pinched. Western states benefit from large reservoirs that can store, in some cases, two to four years of a river’s average annual flow. As long as the dry times are short, water users can draw from the water banked during the years of plenty.

According to National Water and Climate Center data, reservoirs in most Western states are at or above the average storage capacity for this time of year. Arizona and New Mexico are exceptions, but even in those states, the averages hide the variation among individual systems.

-Jeff Lane, Salt River Project spokesman

The big reservoirs on the Colorado River — Lake Powell and Lake Mead — are the most visible water supply yardsticks in the West. After a decade of falling water levels, Mead rose more than 10 meters (35 feet) in the year ending October 2011, thanks to abundant snow in Colorado.

But this year, the lake is estimated to drop again. The Bureau of Reclamation estimates that by October 1, 2012 — the beginning of the new water year — Lake Mead will be more than half a meter (two feet) lower than it was at the same time in 2011.

In Arizona, the Salt River Project, which provides irrigation water for 97,000 hectares (240,000 acres) in central Arizona and electricity to the Phoenix area, is still in good shape, says spokesman Jeff Lane. SRP’s reservoirs are two-thirds full, and it is operating without water use restrictions.

“The reservoirs are doing what they’re designed to do,” Lane told Circle of Blue. “They captured water in the wet year two years ago, and they’re storing it for the dry ones.”

Circumstances are starkly different across Arizona’s eastern border, where the Elephant Butte reservoir on the Rio Grande in southern New Mexico is more than 80 percent empty.

“It’s pretty bleak,” said Gary Esslinger, the manager of the Elephant Butte Irrigation District (EBID), which provides water for 36,400 hectares (90,000 acres). Only once since 2003 has the district received a normal supply.

In a normal year, the EBID would send farmers 2.3 meters per hectare (36 inches of water per acre). This year they will receive 383 millimeters (six inches). Last year, the allocation was just 255 millimeters (four inches).

Esslinger told Circle of Blue that the farmers in his district will pump groundwater to replace the surface water deficit. The state allows farmers to apply 3.4 meters per hectare (4.5 feet of surface and groundwater per acre).

In California, meanwhile, an unexpectedly wet March let the Department of Natural Resources increase water deliveries from the state’s network of canals and pipelines. Customers will receive 60 percent of their requested allocations, up 10 percentage points since a first estimate in February.

“This is good news for our water supply as we approach summer’s peak-demand period,” said Mark Cowin, director of Water Resources, in a statement. “But we must remember that we still had a dry winter, despite a partial recovery in March, and we need to be prepared for a potentially second consecutive dry year in 2013, when reservoir storage would be reduced.”

Rain, however, is unlikely to provide much support elsewhere this summer. The National Weather Service predicts that drought conditions will spread from western Texas through the Southwest, Nevada, and interior California, as well as up to central Oregon. Parts of southern Arizona and New Mexico could see some relief from summer monsoons.

Hydropower

Last year, wind producers cried foul when the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), the federal agency that sells hydroelectric power and operates the major electrical grid in the Pacific Northwest, curtailed wind generation because of the high volumes of water flowing in the Columbia River.

Heavy flows in the Columbia had created an “oversupply” condition, in which more power was generated than the grid could handle. The BPA spilled some of the water over the dams, instead of sending it through the turbines where it would generate power. But spilling water also churns the river downstream, increasing the amount of dissolved gases it holds.

To protect fish, federal and state regulations for dissolved gases limit how much of the surplus water can be handled this way. When an oversupply occurs, the BPA will try to give away power for free, but if there is still too much supply, the agency tells other producers to shut down temporarily: first coal and natural gas plants, then wind turbines.

Wind operators were irritated, because they receive tax credits based on the amount of energy they produce — less generation equals less money. They also felt that the federal government was favoring its own power sources. BPA is now working on a compensation program.

BPA spokesman Mike Hansen says the hydrologic conditions this year are not as extreme, but it is still too early to say for sure whether they will lead to an oversupply of electricity. In 2011, the Columbia’s water runoff through July was 39 percent above average. This year, the runoff forecast shows the river flowing 5 percent above average. Spring rains or a late-season snowfall, however, could change that.

Two other factors contributed to the electrical bulge last year.

- A cold spring reduced demand in the California market, which typically soaks up any excess power from the Pacific Northwest.

- And California’s own dams were running fullbore, because of a deep snowpack in the Sierra Nevada.

Complicating this year’s energy supply equation even further is another power source that will claim grid space. The Columbia Generating Station, a nuclear plant in Washington state, is operating again after being shut down for repairs last year.

All in all, the National Water and Climate Center, in its April snowpack summary, concluded that “spring precipitation could once again create some more interesting water management dilemmas like we’ve seen in recent years.”

While high flows can overwhelm the power grid, lower reservoirs lead to a decline in electrical generation. At Hoover Dam, on average, hydropower capacity decreases 5.7 megawatts for each one-foot drop in the water level at Lake Mead.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Just wanted you to see sandtech’s web sites to see the importance of volunteers and how they are the answer for a rising river flood.