Burdens of Extraction: The Growing Coal Mining Industry in Australia’s Hunter Valley Wine Region

Farmers and small town residents grapple with the pressures of an unprecedented expansion in coal mining.

By Aaron Jaffe

Circle of Blue

MUSWELLBROOK, Australia — The town of Muswellbrook, here in the fertile Hunter Valley in northeastern New South Wales, has always been a little rough around the edges. The overhangs of the two-block-long main street shade entrances to taverns and outfitters where sturdy boots and deep-brimmed hats line dusty shelves. Bars alternate between sports and karaoke on weeknights; locals down cold brews from taps that are generations old.

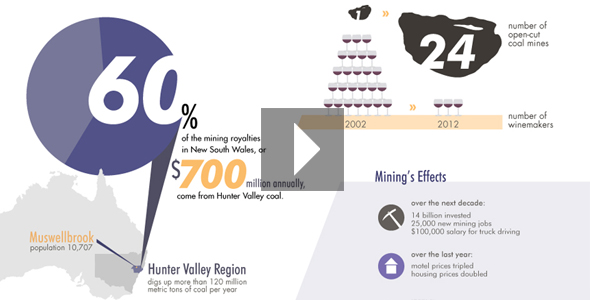

But a torrent of new investments in mineral leases, coal mines, and excavating equipment is changing the look of the local economy and giving Muswellbrooke the most significant development boost it has ever seen. Over the past 10 years, soaring global demand for coal has transformed the Hunter Valley farming region — which also boasts Australia’s premier equine industry and some of its best wine valleys — into a global hydrocarbon center that hosts 24 open-cut coal mines and the world’s most complex coal supply chain operation.

Mines here dig up more than 120 million metric tons of coal a year, most of which is shipped to the power stations and steel furnaces of Asia. With coal prices expected to remain above $US 100 a metric ton, expansion of the 24 existing mines and the start-up construction on new mines is expected to double the production coming out of the Hunter Valley over the next 18 months.

The Hunter Valley also is the focal point for an industry that has been a financial boon to the New South Wales state government and the Australian national government — mineral royalties account for nearly 10 percent of Australia’s GDP and half of its exports. But the massive mining development is putting tremendous pressures on Australian communities like Muswellbrook.

What is going on in the Hunter Valley is emblematic of the struggle in other regions of Australia and across the world as an unprecedented global expansion of hydrocarbon production, often in prime agricultural areas, is setting agriculture and energy users into a fierce competition over the land and water they both depend on.

Coal Mining Reaches New Level of Intensity

Though Muswellbrook hosted one small coal mine for over a century, large-scale mining did not start here until 2002, with the construction of the Bengalla coal mine. The presence of a single big mine, or even a few, gave the town a nice economic boost. But the genesis of the region over the last decade into a mining center has had disastrous economic effects on this town of 10,000 residents.

Energy companies have clashed with farmers in the Hunter Valley over where the mines will be built. Since mineral rights belong to the state — farmers only own the topsoil — plans for a new mine can either translate to a payout or a need to relocate the business. The expanding sprawl of coal mines throughout the valley has edged out many farmers and undercut the property values of others who want to move out of the region but are unable to sell their land adjacent to massive coal mines.

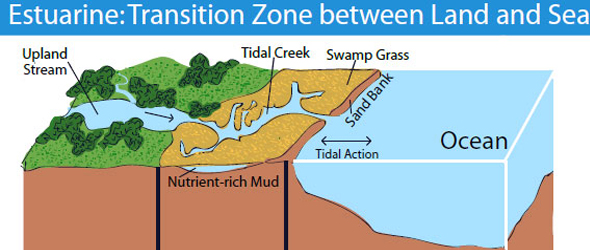

“The strip coal mining that you see in the Hunter Valley is just ecologically disastrous, because you are digging up the entire landscape, completely changing the hydrology,“ Dr. James Pittock, researcher at the Australian National University in Canberra, the nation’s capital, told Circle of Blue.

Open-cut coal mining requires stripping away the landscape until miners can blast away at coal deposits, creating a pit that sinks hundreds of meters into the earth. This kind of excavation irreversibly transforms the landscape with the mine and its tailings.

Strip mining has additional impacts below the surface. Keeping the mine dry requires draining any hydrology that runs through the excavation. This can drain aquifers in the surrounding area, sucking dry the water that nearby farmers rely on for irrigation.

Mining can also make water more expensive for agricultural users when they need it most.

Australia distributes its water allocations through a market. If a user has a surplus, that individual can sell it; if a user needs more, more can be bought.

Mining accounts for only 1.5 percent of the total water use in New South Wales, while agriculture uses 44 percent, according to the state’s Minerals Council. Despite its small slice of the pie, agricultural users argue that the increase in mining drives up the price of water to untenable prices during dry times.

Labor Pool Dries Up

Examining his oak barrels in his vineyard, John Cruickshank remembers when he started growing grapes in the 1970s and the Hunter Valley had only one coal mine and 25 wineries. On the highway running south from Muswellbrook, sun-bleached signs still advertise the valley as Australia’s wine country.

Like many others, Cruickshank has a hard time finding the labor force he needs to nurse his vines into wine. “It’s very hard to find workers and very hard to find subontractors,” Cruickshank told Circle of Blue.

As coal mines have blossomed from one to 24 over the last decade, the number of winemakers has dwindled from 25 to three. This kind of attrition is shared by other types of agriculture across the region.

Mining jobs with lucrative high salaries have dried up the pool of workers available for farmers, causing a labor shortage for the agriculture industry that has, at times, meant fields go unharvested. For instance, unskilled laborers earn a starting annual salary of over $US 100,000 working 12-hour shifts as truck drivers in the coal mines. Farmers that hire for truck drivers or farmhands pay much more modest wages and cannot compete with the salaries offered by the mines.

Remembering the days when the region was rich with vitoculture, Cruickshank said the mining industry has taken “a divide and conquer approach… They are so wealthy that they upset the balance completely.”

Two-speed Economy

Muswellbrook is a two-speed economy, and local tax revenues have remained in low gear. Though coal mining extracts billions of dollars of resources, little of it — less than 1 percent — trickles back to Muswellbrook’s shire coffers.

In other words, those employed by the mines prosper, while the town and those outside of the mining economy are unable to keep up with rising prices. Despite the coal boom, in real terms, Muswellbrook has gotten poorer, according to Muswellbrook’s mayor, Martin Rush.

Coal mining in the Hunter Valley brings billions of dollars out of the ground annually, generating $US 700 million in mining royalties for New South Wales, which accounts for 60 percent of the state’s total mining royalties. However, despite being an economic boon for the state, Muswellbrook’s local government received below-average funding from the state for infrastructure and capital works projects.

Coal Mining Reaches New Level of Intensity

Though Muswellbrook hosted one small coal mine for over a century, large-scale mining did not start here until 2002, with the construction of the Bengalla coal mine. The presence of a single big mine, or even a few, gave the town a nice economic boost. But the genesis of the region over the last decade into a mining center has had disastrous economic effects on this town of 10,000 residents.

And while the town receives little funding for public works, Muswellbrook scrambles to keep up with the stress exerted on the region’s roads by heavy mining equipment and the nearly endless stream of cars carrying miners and contractors. Mining has led to a huge influx of workers willing to make the pre-dawn drive, or stay in hotels during the week.

The rush of workers is prompting a huge housing crunch. Home prices have skyrocketed, doubling within one year. Motel rooms that normally go for $US 30 to $US 50 a night have crept to $US 150 to $US 200, with some accommodations booked months into the future.

“All of those markets have become overcooked,” Mayor Rush told Circle of Blue.

On the other side of the coin, the mining industry focuses on the new investment and job creation in the region. The industry projects that, over the next decade in the Hunter Valley, $US 14 billion will be invested and 25,000 new jobs will be created.

Representatives of the mining industry focus on calming the concerns of communities and weighing the benefits mining brings.

“It must be so tempting, when in government, to respond quickly to concerns in the community and sticky political situations,” Sue-Ern Tan said in a 2011 speech. Tan is deputy CEO of the New South Wales Minerals Council, the peak organization that represents the mining industry in the region. “But when we are talking about investments in the billions of dollars, jobs in the thousands of people, and the future of the industry that is responsible for 17 percent of private investment in the state, caution and cool heads are required.”

When asked what will happen if the mining boom slows down, or the area runs out of coal, Mayor Rush said he is confident that mining will continue to accelerate into the foreseeable future.

In mapping the future of the region, Muswellbrook’s mayor posited that it is all about developing in moderation to ensure that the town is not unsustainable when mining slows down. He admitted that a transition away from coal will be painful, and the outcome of whether Muswellbrook will return to its roots as a farming community — or become a ghost town — is ambiguous.

Others say they already see the writing on the wall. At run-down motels, owners revel at the windfall-profits they get from the mining boom. They know it will end, but don’t care.

From a run-down supply room with cigarette smoke enveloping his dimly lit sihouette, one motel owner told Circle of Blue that he is happy to see the mines expand. As soon as business slows, if it ever does, he will have the money to move out, away from the open-cut pits and tailing piles.

Burgeoning Coal Mines Look to Expand North

For the time being, the Hunter Valley’s large-scale coal mining is an accepted reality. Residents, miners, and the local government all see its expansion as inevitable; the coal below the region’s topsoil is too lucrative to pass up. However, as energy companies tear through the coal deposits here, they are also focusing their future mining ambitions northward, to the adjacent Liverpool Plains.

But residents here in Muswellbrook, residents give knowing looks about what is in store for ther neighbors.

Perched on a stool in a tavern at the corner of downtown’s main steet, Damen Marrick, a life-long Muswellbrook resident, pauses over a pint of Tooheys. Marrick has worked a string of jobs in and around the mines, from truck driver to mechanic. He says that he would not wish what has happened to Muswellbrook on any other part of the country.

“There are no jobs other than the mines,” Marrick told Circle of Blue. “It’s creating jobs, but the locals aren’t getting the jobs.”

Peering up from under the brim of an orange trucker hat, Marrick says he would never raise a family in Muswellbrook. He believes the town will be dead soon, as soon as the mining slows down. Even as others salivate over the wealth coming out of the ground, Marrick sees little hope for Muswellbrook — to him, it is already a wasteland.

“All you can do is eat, drink and piss here,” Marrick said, before returning to his beer.

This is the third story in a three-part series about Australia’s coal and coal seam gas boom. Read the first story on the global demands that are driving Australia’s coal and gas export boom and the second story on agricultural clashes with the coal seam gas industry on the Liverpool Plains.

Reporting in Australia was supported in part by an Eric Lund Global Reporting and Research Grant at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism.

Aaron Jaffe is a Chicago-based multimedia producer for Circle of Blue. Amanda Northrop and Alec Aja are undergraduate students at Grand Valley State University and Traverse City-based design interns for Circle of Blue. Reach them at circleofblue.org/contact.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!