Clean Water Act Turns 40 (Part II): A Harvest of Clean Water Exemptions on the Farm

The U.S. farm sector, more productive and richer than ever, is a major water polluter.

By Codi Yeager-Kozacek

Circle of Blue

In 1972, when Congress enacted the Clean Water Act, it was still possible to see North Carolina farmers using mules to plow their tobacco, cotton, and corn fields. A big Wisconsin dairy farm fed 100 cows in one milking barn. A typical Nebraska cattle feedlot measured a few hundred acres. In Washington, D.C., lawmakers still viewed the American farm as a family-owned and -managed enterprise, and not much of a threat to the nation’s water.

Forty years later, according to the federal Environmental Protection Agency and state water quality departments, the agriculture sector is the largest producer of nitrates, phosphates, chlorinated compounds, sediment, and other major sources of water pollution. Moreover, even as farms expanded in acreage and animal products — meat, milk, and eggs — were produced in factory farms and feedlots that housed thousands of animals, farming wastes were largely exempted from water clean-up standards that were required of other polluting industries.

The result is that, while the Clean Water Act has curbed the worst industrial and municipal pollution and restored many of the country’s iconic rivers and lakes, agriculture and other nonpoint sources of pollution have largely fallen beyond the legislation’s reach. Agricultural pollution has produced an oxygen-depleted dead zone near the mouth of the Mississippi River in the Gulf of Mexico. Agricultural fertilizer running off land in Wisconsin and Ohio generates thick algae blooms in Lake Michigan and Lake Erie.

According to the EPA, the most prevalent form of agricultural water pollution is sediment that is washed into streams and lakes from farm fields. However, it is nutrient pollution — when excess phosphorous and nitrogen from fertilizers and manure make their way into water — that can foster harmful algal blooms. When the blooms die and decompose, the process takes so much oxygen that the surrounding waters can no longer support fish and other aquatic animals, forming a dead zone. Algal blooms can also make water unsafe for swimming or turn it a slimy, smelly green that deters recreational use.

Nutrient fertilizers have become instrumental in improving the world’s agricultural crop yields and will likely be necessary to grow enough food for the estimated global population of 9 billion people by 2050. But agriculture accounts for 70 percent of the nitrogen and phosphorous that flows into the Gulf of Mexico, while urban sources account for only about 12 percent, according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

Nutrient pollution is a difficult issue to address, because nutrients like phosphorous and nitrogen are not just from agricultural runoff — these nutrients occur naturally in the environment and are also necessary for ecosystem functioning. Nonetheless, excess nutrients are a threat to clean, safe waters — and they pose a problem that has, so far, fallen beyond the scope of the Clean Water Act.

Steps Toward Stricter Regulation

Under the Clean Water Act, most farms fall into the category of nonpoint sources of pollution. In other words, they do not directly pipe polluting materials into the water. Rather, the pollutants are transferred to rivers and lakes via snow and rain runoff. Therefore, nonpoint pollution sources are not required to obtain a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit, which places a limit on how much effluent the permit holder can discharge into a body of water.

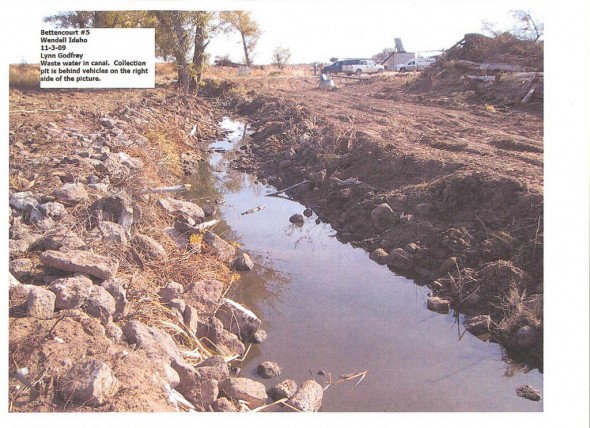

One exception is Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), which are facilities where large numbers of livestock or poultry are confined in a small area. CAFOs are considered point source polluters by the EPA and must have a NPDES permit. But the permits, criticized by environmental groups, do not require such large animal feeding operations — which typically produce as much wastewater as a small city — to process wastewater in sewage treatment plants. Instead, CAFOs can spray wastewater on farm fields or store manure in big lagoons.

The risks to water quality are enormous.

In 1999, a hurricane dropped so much rain on North Carolina, the nation’s second-largest hog producer, that manure lagoons overflowed, contaminating hundreds of thousands of acres of land, swelling streams with hundreds of millions of gallons of raw filth, and causing one of the worst industrial water pollution and public health emergencies in U.S. history.

–Cristina Llorens, manager of communications

National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA)

To curb pollution from the remaining majority of farms — as well as municipal sources of nutrient pollution — some conservation groups have suggested that it is necessary to place numeric limits on the amount of phosphates and nitrates allowed in a body of water. Numeric limits would replace narrative standards, historically used by most states, which describe the quality of water needed for a body of water to be used for a designated purpose. States are required to use one of these two methods to enforce water quality laws under the Clean Water Act, though the EPA urged states in 1998 to start setting numeric nutrient criteria.

“[Narrative standards] are unenforceable,” David Guest, the managing attorney at Earthjustice’s Tallahassee office, told Circle of Blue. “Numeric limits would act like speed limits. Now in Florida, instead of a [metaphorical] speed limit sign, you have something that says ‘Don’t drive so fast as to become dangerous.’”

Earthjustice, an environmental legal advocacy group, has been fighting for numeric nutrient limits in Florida since 2008, when it sued the EPA on behalf of five environmental organizations. The EPA consequently proposed a set of numeric nutrient criteria for Florida in 2010, which many industries in the state — including agriculture — opposed.

The EPA’s proposed numeric nutrient limits are not grounded in science and would be too costly to implement, according to Cristina Llorens, manager of communications at the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA).

“Cattle producers in Florida go to great lengths to protect water quality; their livestock and families depend on it,” she told Circle of Blue. “The Clean Water Act has done great things, and a large piece of its strength is the state-federal partnership that it created. However, recent actions by the [EPA], including the issue with Florida’s Numeric Nutrient Criteria, have disregarded this carefully crafted partnership and pushed the state of Florida aside in a process where the state was already engaged and trying to address any issues.”

The EPA estimated that implementing its new rules across all sectors — municipal, agricultural, and industrial — would cost a total of $US 135.5 million to $US 206.1 million each year, though these figures have been a source of much debate. A separate analysis by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACs) and the University of Florida, for example, suggested that initial implementation costs could be between $US 855 million and $US 3 billion for agriculture alone, with annual costs ranging from $US 271 million to $US 974 million annually.

The rules are still up in the air, as Florida state has since created its own numeric nutrient criteria, signed into law in February. The state regulations are currently pending EPA approval.

Another Approach: Water Quality Trading Programs

Other states and organizations have taken steps to reduce nutrient pollution without imposing new or stricter regulations under the Clean Water Act. The Ohio River Basin Trading Project, a water quality trading system based on economic incentive, is one such effort.

The project is organized by the nonprofit Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) headquartered in Palo Alto, California. It is the first interstate water quality trading program in the United States, as well as the largest program in the world to operate under a single plan. In August, Indiana, Kentucky and Ohio signed an agreement to perform pilot trades over the next three years.

Under the pilot plan, nonpoint sources of pollution — like farms — can generate water quality credits by implementing conservation best management practices (BMPs) to reduce their nitrogen and phosphorous input into the Ohio River Basin.

EPRI then pools all of the credits and puts them up for sale in a marketplace, where point source polluters — like power plants — can buy the credits to offset their own pollution. Other stakeholders, such as conservation groups, are also able to buy the credits and retire them to benefit water quality.

“For the buyers, this gives them a more cost effective way to meet their [NPDES] permit limits,” said Jessica Fox, the senior project manager. Farmers also see benefits. “The conservation practices can improve crop yield and increase wildlife habitat — things that are fundamental to running a successful farm. We have more interest than funding at this point.”

But much like carbon credit trading, water quality credit trading systems have been criticized on the grounds that they will not actually provide any in-stream benefits and that they could become susceptible to fraud.

–David Guest, managing attorney

Earthjustice’s Tallahassee office

EPRI has taken steps to address these concerns, Fox told Circle of Blue. Conservation practices must be put in place and verified by a third party before they can generate any credits, and the organization is using a full watershed model to determine what effect a one-pound reduction of nitrogen on a farm will have downstream at the power plant that might buy its credits, since this is not always one-to-one ratio. In addition, EPRI will retire a percentage of all credits produced to provide a safety net.

“Of all the nutrient reductions, we put 20 percent into a reserve pool for a margin of safety,” Fox said. “So not only are we using one of the best calibrated models, our safety margin is huge: the EPA only requires 10 percent, and we were actually told we could even go below that because of the model we use.”

Nonetheless, Fox said it will take time for environmental benefits of the trades to show up — especially as far downstream as the Gulf of Mexico. The pilot program, with its limited budget, will likely have no effect on the dead zone there, and the trading system as a whole has its limits.

“Water quality trading is only one tool, and we need a whole suite of tools,” she said.

This article is part of a series marking the 40th anniversary of the Clean Water Act. Click here to read Part I: Cities Fall In Love With Rivers Again by Circle of Blue’s Seattle reporter, Brett Walton. Click here to see a slideshow of vintage photos, taken before the Clean Water Act was implemented.

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Personally I think it is rather hypocritical to go after farmers, when cities still can use open waters as urinals. EPA is solely focused in reducing the oxygen depletion caused by carbonaceous (fecal) waste and ignores all the nitrogenous (urine and protein) waste in sewage. According to the EPA urine waste does not require to be treated under the Clean Water Act and EPA only will set ammonia limits if certain rivers are sensitive for ammonia. This according a recent article in http://www.invw.org. What EPA apparently does not know is that nitrogenous waste in sewage directly exerts an oxygen demand, nearly 60% of that caused by fecal waste, but more important nitrogenous waste is also a fertilizer for algae and for each pound of nitrogen one can expect about 20 pounds of alga, which after it dies will exert an oxygen demand similar, but much larger than that caused by the fecal waste. Without removing nitrogenous waste from sewage, one might as well dump the raw sewage directly into our open waters. All this, by the way, is caused by the fact that EPA, when it implemented the CWA used an essential test incorrect and ignored 60% of the pollution in sewage Congress intended to treat. So before we blame farmers, let’s first clean up our own waste.