Climate Change Alters the Calculus for Water Infrastructure Planning

Adapting to climate change in the U.S., according to one estimate, will cost at least a half trillion dollars over the next four decades.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

When the water and sewer agency for metropolitan Boston decided to raise parts of the Deer Island sewage treatment plant in the city’s harbor by half a meter (two feet) as a hedge against climate change and rising sea levels, it was not a policy decision.

“It was the engineers who pushed it,” said Steve Estes-Smargiassi, the director of planning for the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA).

The major urban utility’s decision to protect an expensive coastal facility should not arch eyebrows in an age when the Atlantic Ocean, off the eastern coast of the United States, is rising at its fastest rate in the last two millennia, according to a 2010 study. Except that the adaptation planning for Deer Island happened in 1989, three years before the Kyoto Protocol and one year after NASA scientist James Hansen’s Congressional testimony brought public attention to global warming.

Deer Island was one of the first instances of climate change projections being incorporated into a sewage plant’s design, Estes-Smargiassi told Circle of Blue. Now, more than 20 years later, as the detrimental effects of climate change have become better understood at global, national, and regional scales, more people are asking how a warmer, wetter world will alter the function and effectiveness of vital infrastructure in the U.S. However, when it comes to planning for the effects on drinking water and sewer systems, many cities, for a variety of reasons, still are lagging.

Most municipalities are more concerned with stanching the immediate leaks from an aging distribution system, as Circle of Blue reported on Monday. Without sufficient funds to fix today’s problems or access to sophisticated climate simulations, these utilities are more worried about today’s problems than the incremental changes that will develop over the next decades. Some utilities are a step ahead and have begun the assessment phase, developing models to understand new rainfall patterns and river flows. And a few of the most pro-active are already making their water systems more resilient by changing policies, building new structures or revamping old ones.

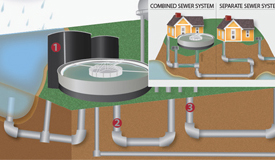

Though the environmental circumstances for each region of the U.S. are unique, the cost of adaptations nationwide — backflow prevention in sewer pipes, expanded stormwater retention, green infrastructure investments, desalination plants, wastewater recycling — could amount to hundreds of billions of dollars in the coming decades. These investments will come at a time when water infrastructure, in general, is deteriorating and in need of replacement.

In some places, the inadequacy of the old system is already showing.

Surrounded on three sides by water, San Francisco has begun to see the effects of higher seas and higher tides on its stormwater collection pipes. The city’s water utility anticipates spending $US 20 million to $US 40 million over the next five years to prevent backflow into the system, where the salt water can compromise the biological treatment process.

“There are 29 stormwater sites that will go from a nuisance to a problem,” said David Behar, the climate program director for San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. “We know that these types of impacts will only increase in the future because of climate change.”

Done well, like the Deer Island facility, the nation’s pipes and plants can concurrently be remodeled and made climate resilient. But with poor planning or no planning at all, these assets will need to be re-fitted — at great cost — well before their useful life has expired.

A Model Exercise

A report released last August by the Natural Resources Defense Council considered the effects that climate change might have on water resources for 12 American cities. Though New York, Chicago, Seattle, and San Francisco had decent assessments, according to Michelle Mehta, one of the report’s principal authors, the goal of canvassing 15 cities was not met because of a lack of good information.

Even the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), when it collects data from states on capital needs for water and sewer infrastructure, does not ask how climate change might influence the numbers. The most recent figures, collected during 2007 and 2008, estimated that utilities would need to spend $US 298 billion on wastewater and $US 335 billion on drinking water over the next two decades.

The EPA told Circle of Blue that the 2011 drinking water survey, which is underway and will be reported to Congress in 2013, will for the first time ask what infrastructure needs are attributed to climate change preparations.

The first attempt at a national figure for the cost of climate change adaptation to water utilities came in 2008 from a study by the National Association of Clean Water Agencies (NACWA) and the Association of Metropolitan Water Agencies, two lobby groups for public utilities. They estimated that U.S. water and sewer agencies would have to spend between $US 448 billion and $US 944 billion from 2010 through 2050 on infrastructure, operations, and maintenance. The Southwest — defined as Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah — would have to spend the most to adapt.

One of the reasons some cities have not taken up the issue is expediency. They are more concerned about finding money to fix today’s broken sewer line or to meet the latest water quality standard, according to Adam Krantz, the managing director for government and public affairs for NACWA.

“How do you determine your priorities when there are other issues at hand?” Krantz told Circle of Blue. “Utilities do not necessarily consider that long-range planning when they don’t have the funds to meet the immediate problems.”

A second factor is technical. Most climate models do not provide the “granularity,” or minute-by-minute, neighborhood-by-neighborhood details that are required for an accurate evaluation of stormwater flows. Furthermore, regional climate models may not provide a clear enough picture of what could happen in a particular watershed.

Sea-level rise, however, has been easier to run through the computers. Most adaptation investment, such as Boston’s Deer Island sewage plant, has been directed to that area.

View U.S. Cities and Climate Change in a larger map. Map © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

Source: Mayors Climate Protection Center, National Resources Defense Council

Design for the Future

Like most coastal facilities, treated wastewater flows away from Deer Island with the force of gravity. The Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) feared that, if the seas rose, the sewer outfall would have a lower flow rate, especially during high tide, because of pressure differences. Gravity would become ineffective, and pumping would then be necessary. Instead, the utility built the holding tanks 0.58 meters (1.9 feet) higher at the outset, to compensate for the expected change.

“In designing the sewer outfall, which has a life of up to 100 years, folks had to think about the capacity during tides,” Estes-Smargiassi told Circle of Blue. “Someone on the engineering team asked about sea-level rise.”

Those are questions that more utilities are beginning to think about. Though most are not taking bold actions yet, they are assessing the situation, gathering information, and refining their computer simulations, said David Behar, the climate program director for San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. Behar is also the staff chair for the Water Utility Climate Alliance, a group of 10 large U.S. water utilities collaborating on climate change issues.

“Utilities can ask, ‘What will the effects be?’” Behar told Circle of Blue. “And they can ask, ‘How do we make ourselves resilient?’ The second question can only be answered after the first. Right now, we’re not asking ‘How?’ We’re asking ‘What?’ And that has not been satisfactorily answered by anyone.”

Paul Fleming, the manager of the climate and sustainability group at Seattle Public Utilities, told Circle of Blue that he used to feel apologetic when he told people that the city was in an assessment period. “But now, I think it’s the place to be,” he said. “I think there’s been buyer’s remorse in Australia, for example, because of all the investment in desalination plants. We have to ask ourselves, ‘When do we make those large purchases?’”

Two decades ago, in the middle of a severe drought, the city of Santa Barbara, California, asked the same question and decided to build a desalination plant for emergency supplies. The $US 34 million facility was used for less than a year before the drought broke. The plant was mothballed (or put, as the city says, in “long-term storage mode”), and parts of it were sold off.

The uncertainty in the rainfall models is one argument for green infrastructure, says Fleming, who says that the “cellular” essence of these natural water-absorbing systems — such as streetside wetlands, grassy roofs and permeable pavement — allows for greater flexibility when both average and peak environmental conditions are in flux.

New York is one of several cities to use green infrastructure to address the variability that climate change is expected to bring.

“If you put a pipe in the ground,” Fleming reasoned, “you can’t increase it if you guessed wrong on the size.”

Seattle’s climate assessment program has allowed the city to feel confident that it does not need to make those big capital investments yet, but the city is experimenting with several green infrastructure projects for stormwater. Now is the time for such experiments, argues Richard Luthy, a Stanford engineering professor and the director of the nation’s only federally funded center for urban water infrastructure research.

“This is a special moment for water,” Luthy said in an interview with Circle of Blue, “because of all the pressures — scarcity, increasing demands, and the need to provide water for ecosystem services — all on top of failing infrastructure.”

This article is part of a series on water infrastructure in the U.S. Part one reported the national debate on how to pay for repairing and upgrading an aging system.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Interesting that this issue isn’t taken more serious.