Film Review: Last Call at the Oasis

A documentary film on the world’s water crisis opens this weekend.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Forget for a moment, if you will, everything you associate with water. Forget the childhood swimming hole and that waterfall in the national forest. Put aside any opinions on desalination or long-distance water transfers. Ignore, only briefly, the debates about natural gas drilling and water wars and chemical contamination and think about the beauty of water itself, the union of H and O in its liquid phase.

This is how Last Call at the Oasis, a new documentary about the world’s water crisis, begins.

Impeccably lit droplets, accompanied by soft waltz music, spritz across the screen. Crystal waves of water bubble and whorl, evoking the stop-motion images of Japanese artist Shinichi Maruyama.

For a few minutes, the world is bright and pure, and water reveals both its power and delicacy.

And yet, if any of the host of water problems brought up in Last Call are to be solved, this type of disassociation must be abandoned, argue many of the people interviewed in the film. Water is used — not just viewed — and that requires getting into the muck of it all and understanding that the same basic substance flows through our food production, clothing purchases, land use decisions, and energy development, as well as our kitchen faucets.

“The biggest mistake in thinking about water has always been thinking about it as disconnected from everything else,” says international water expert Peter Gleick during his interview in the film. Gleick joins a ‘big name cast’ that includes hydrologist Jay Famiglietti, biologist Tyrone Hayes, and drinking water advocate Erin Brockovich.

The World’s Water in 100 Minutes

Last Call has no editorial voiceover to shape the narrative. Instead it relies on archival footage, a cast of star scientists, and a group of hometown environmental champions to act as a team of Virgils to guide viewers through the circles of the world’s water Hell.

And make no mistake, for many of the people interviewed — for those who deal with cancers and respiratory illness, with undrinkable tap water and family farms going under — this is no Divine Comedy. It is Hell.

The film, which opens May 4 in theaters in New York City and Los Angeles, jumps around the globe, alighting on certain spots to point out a particular water issue, from farming in California’s Central Valley and Australia to conflict in the Jordan River Valley to groundwater pollution in Midland, Texas.

With so many problems to choose from, some worthy candidates are excluded and some issues are insufficiently explored, but the writers make good use of the material they have selected. They explain technical issues, while never losing sight of the lives that are affected.

The first stop on this tour is Las Vegas, which is planning a contentious US$3 billion pipeline to tap groundwater in several valleys that are 450 kilometers (280 miles) to the north. Some say that the city should come to terms with its desert location and live more within its means, but it is a lesson that applies broadly.

“It’s easy to point the finger at Vegas,” says Robert Glennon, University of Arizona law professor and author of the book Unquenchable, “but when you look at the future of growth and water, we’re all Vegas.”

So rather than tap distant sources, some cities are looking inward. Wastewater recycling is the highlight in Singapore, where membrane technology turns sewage into potable water and where a public relations blitz has rebranded the product as NEWater. In the pursuit of self-sufficiency, the tiny island city-state anticipates that the recycled water will provide 30 percent of its supply.

But the most poignant moments in the film come from individuals whose health and homes have been forever altered by contaminated water.

At a town meeting in Midland, Texas, which has groundwater polluted with the carcinogen hexavalent chromium, a hairdresser says she has seen more people with cancer and shaved more heads in three years here than she ever saw in her old town.

–Dr. Peter Gleick

International Water Expert

“Our own children are waking up with nosebleeds,” she says.

In Michigan, Lynn Henning, who for years has tested the manure-polluted water coming off of factory farms, visits her doctor who says her lung capacity has dropped by one-third because of breathing the noxious emissions coming off the water that she samples. Henning won the Goldman Prize, given to grassroots environmental leaders, in 2010.

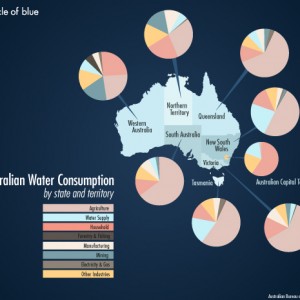

And in Australia, a farm advocate reveals that eight farmers have committed suicide in his district during the decade-long drought that has crippled the country’s rural agriculture areas.

The Bar is Closing

Last Call offers a few solutions but — except for a segment on recycled wastewater — little about how to traverse the tangled political, social, and economic pathways to achieve them. In fact, at times its ‘stars’ show the exasperation and resignation that comes from years spent seeing the tires spin in the same wheel ruts.

Brockovich tells the crowd in Midland that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which oversees national water quality regulations, is broken and will not be able to help them.

“Superman is not coming,” she says.

At an unidentified meeting in Fresno, California, Famiglietti tells the water managers and scientists gathered there that the state has a water crisis.

“I wanted to make clearly this statement that we do face a crisis now, of epic proportions, and I said that,” Famiglietti tells the camera after the meeting. “I’m not sure that it really resonated, which, to me, is a little startling. We need a plan, and we don’t have one and it is complex.” Then, he pauses and with a cold smile says, “We’re screwed, yeah.”

Later, in a less frustrated moment, Famiglietti is more hopeful. “We can take steps to ensure that there is a sustainable water supply over a much longer period of time,” he says. “It’s not a solvable problem, but it truly is a manageable problem. But we need to start addressing it now.”

Identifying those problems is the film’s ultimate purpose. But Gleick believes that this knowledge itself is a good enough start point for solutions.

“There’s no doubt that humanity is capable of screwing things up,” he says. “There’s also no doubt in my mind that we’re capable of fixing things, when what we’re screwing up is really important to us. The more we know, the more likely we are to do the right things. In the end, you do what you can.”

For some people, that means pushing polluting companies to clean up their mess; for others, it is studying the hydrologic cycle so that we know what changes to expect in our water supply. Still others, like those involved with this film, collect these stories and spread them to the public.

Watching Last Call, and thinking about a topic of universal relevance, is the least one can do.

Directed and written by Oscar award winner Jessica Yu, Last Call had its premiere last September at the Toronto International Film Festival. It has since been featured at the Berlin International Film Festival and the South by Southwest Film Festival.

Disclosure: Circle of Blue is an independent affiliate of the Pacific Institute.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!