Global Perspectives: How Dry Weather in Argentina Could Affect Chicken Prices in Chicago

A South American drought keeps global grain reserves tight, but it could mean good things for North American corn producers.

By Codi Yeager

Circle of Blue

Though farmers are improving farm practices and productivity, the planet’s growing population — now seven billion — and fickle dry weather in the world’s important food-growing regions are steadily narrowing the margin between surplus and scarcity. The result, here in the United States and in markets worldwide, is persistently high prices that shoppers pay for beef, chicken, pork, milk, and bread.

This year, the problem region is in South America. A drought in Argentina, the world’s second-largest corn exporter behind the United States, may cut nearly one-third of the country’s production of corn, a staple grain for much of the world.

Last week’s rain looks to have provided enough moisture to save some of the corn that was planted in November, said Argentine agronomists. But the drought has spread to Brazil, where farmers said they expected lower harvests of corn and soybeans.

— Kristin Wedding

Global Food Security Project

Coupled with 2010’s abnormally scorching weather in Russia, which reduced harvests of Russian wheat and drove bread prices to near-record levels globally, the South American drought is another example of how severe weather patterns are creating volatility in the food market, raising the cost of food — in some cases causing scarcity — and putting food and political security at risk.

“The droughts going on now are really scary, because, when you see a big producing country like Argentina losing one-third of its crop, it has the potential of really impacting global markets,” Kristin Wedding told Circle of Blue. Wedding is a fellow at the Global Food Security Project of the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Strategic and International Studies. “Food prices in 2012 have stabilized a bit, but they are still close to record highs.”

1M tonnes of corn = 200M chickens

Argentina’s drought began last fall but deepened in January, when record temperatures were set. Though a bit of rain arrived earlier this month, it was too late for most of the corn crop, prompting forecasters to cut production estimates from over 30 million metric tons to 22 million metric tons. Last year, Argentina produced 26 million metric tons.

Scarce rain also is expected to lower Brazil’s corn harvest to 59.8 million metric tons, which is 1.2 million metric tons less than the original harvest forecast for the year. And Brazil’s soybean harvest is expected to be 71.7 million metric tons this year, down from the expected 74 million metric tons.

The difference in the numbers may sound small, but, in the supply-tight era that now distinguishes global food stores, they are not — one million metric tons of corn is enough to bring 200 million adult chickens to the market; one million metric tons of soybeans produces 3.3 million adult hogs.

The crop shortfalls in Argentina and Brazil will lower global corn ending stocks to 125.4 million metric tons, the lowest since the 2006-2007 season and 18.8 million metric tons less than levels in 2009-2010. The drought will also impact global ending stocks for coarse grains, which include corn, as well as sorghum, barley, oats, rye, millet, and mixed grains. Two years ago, global coarse grain stored in the world’s grain bins reached 195.4 million metric tons, while this year they will only reach 158.5 million metric tons, according to the February World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates report from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

The gap left by Argentina and Brazil will be filled, to a large extent, by the United States. But the uncertainty caused by the Argentine drought has raised corn prices globally. One bushel of corn currently costs $US 6.23 to $US 6.47 ($US 249.2 to $US 258.8 per metric ton).

“Corn prices have been relatively strong, and commodities have been strong in general,” said Nathan Fields, director of biotechnology and economic analysis at the National Corn Growers Association in St. Louis.

Typically, corn prices are between $US 4 and $US 6 per bushel ($US 160 to $US 240 per metric ton), he added. “The Argentine drought is supporting strong corn prices around $6, so we are at the high end of that range, but not at a peak.”

In agriculture — as in markets for energy, minerals, and other commodities — one region’s hardship is often another region’s opportunity. The Argentine and Brazilian drought, for example, is expected to prompt U.S. farmers to plant 32.96 million hectares of corn, or 1 million hectares (2.47 million acres) more than last year. The USDA estimates that American corn growers will export an additional 1 million metric tons, or nearly 46 million bushels, more than in 2011.

— Nathan Fields

National Corn Growers Association

“Volatility happens in regions throughout the world,” Fields said. “Typically, if one region is doing poor from weather, another is booming from weather.” And, while Argentina’s corn crop has suffered from the drought, other Argentine crops, like soybeans, have not suffered the same kind of damage because of when their planting seasons are, thus they could flourish in the coming months. “Little nuances in timing, when the rains come, can have a dramatic effect on how a crop turns out.”

Weather, Food Prices, and the Arab Spring

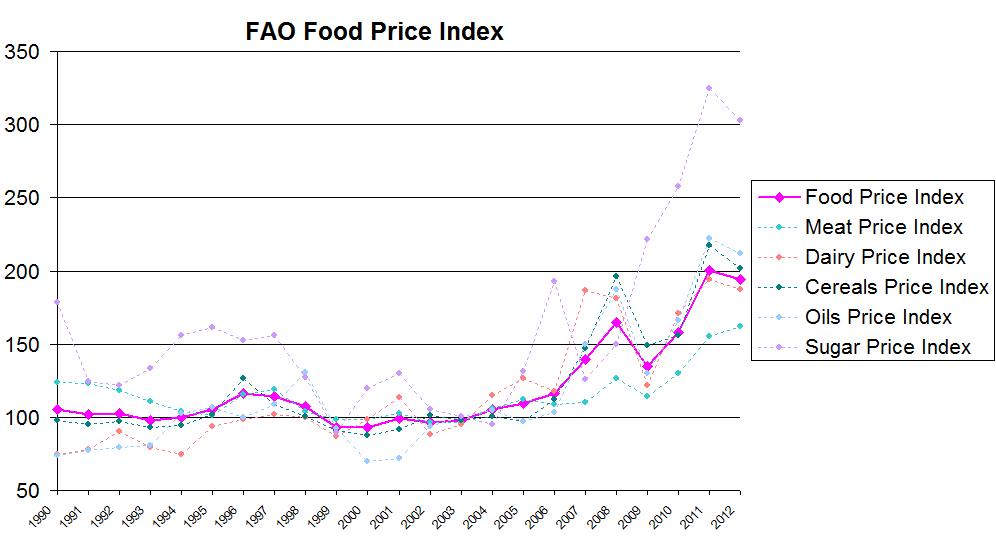

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s Food Price Index, which measures the average international price of a basket of food commodities, averaged 214 points in January, which was up four points from December, but below its peak of 238 points in February 2011. From 2000 to 2006, a period of relative surplus and price stability, the Food Price Index ranged from a low of 90 to a high of 127. Since then, however, the index has steadily climbed and averaged 181.4 points between 2006 and 2012.

An FAO report, released in October 2011, predicted that global food prices would remain volatile in the future, in part due to climate change. The Food Price Index is being closely watched because of how food prices and shortages can be linked to global volatility and social change. For example, spiking food prices in 2008 and 2009, coupled with rice shortages — caused, to some extent, by the climate-related collapse of the Australian rice industry — prompted rioting in Asian cities. Additionally, diplomats and Middle East scholars say that high food prices and shortages also contributed to the revolutions in Egypt and several other Arab countries last year.

Prices for corn, wheat, and rice are particularly important, because the crops are used to produce so many foods, from cereals to feed for livestock.

When drought hits a region that produces these crops, the effect is two-fold, said Wedding, of the Center for Strategic and International Studies. First, local subsistence farmers are often unable to grow enough food to feed themselves, let alone have any leftover to sell. Food prices then rise due to uncertainty and dropping supplies, which forces the poor to spend even more of their income to eat.

Mexico, which has been gripped by a series of recent droughts, is a case in point. Tortilla prices are rising again this year, as the country continues to experience its worst drought on record.

The effects of the drought in Argentina could be similar.

“It will be felt most locally and among the poorest of the poor on the global market, especially those living in food-importing countries,” Wedding told Circle of Blue. “Climate change and extreme weather impact basic food supply and make it unpredictable. Countries and farmers can’t rely on predictable food crops.”

La Niña

Meteorologists say the cause of this year’s South American drought is La Niña, a weather phenomenon characterized by colder-than-normal water currents along the Pacific coast of the Western Hemisphere.

The El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) climate pattern is a coupled ocean-atmosphere phenomenon consisting of El Niño and La Niña cycles. 2010 was classified as a moderate-to-strong La Niña, following 2009’s especially intense El Niño year. La Nina conditions returned in the fall of 2011 and are currently considered weak, with a forecast for ENSO-neutral conditions by May 2012.

According to the United Nations Environmental Programme, although ENSO is naturally occurring, a warming climate may contribute to an increase in the frequency and intensity of El Niño cycles. The effects of La Niña, however, can be hard to predict.

“It is not a perfect relationship,” said David Brown in an interview with Circle of Blue. Brown is the southern region’s climate services director for National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Brown said that two winter-time La Niña events — one in 2010-2011 and the other in 2011-2012 — have yielded very different results in the U.S.

“Last year it was very dry, and this year it is much more variable,” he said. The U.S. drought, which has been plaguing Texas and the Southwest since the end of 2010, is expected to persist into April, according to the U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook, released by the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center.

La Niña is one of the primary culprits behind the long-running drought in Texas and Mexico, and the amount of snowfall during a La Niña winter could also lead to drought conditions the following summer.

“There are theories that the amount of snow on the ground does have an effect on storms and climatic conditions,” Brown said. “It is a new area of research, but we are looking at the relationship between snow cover and dry and wet conditions.”

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!