In These Dry Times, Groundwater Rescues New Mexico Farmers

Surface water allocations last year were 10 percent of normal, but record levels of groundwater pumping buoyed production in the state’s top agricultural region.

Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

In a normal year, farmers in the Elephant Butte Irrigation District (EBID) along the Rio Grande in southern New Mexico receive 2.3 meters of irrigation water per hectare (36 inches per acre) from Elephant Butte reservoir. With it, they grow pecans, alfalfa, cotton, and a mix of vegetables on nearly 36,400 hectares (90,000 acres) of loamy soil in the state’s top agricultural area — Doña Ana County, which comprises most of the district’s acreage, is the top pecan producer in the United States.

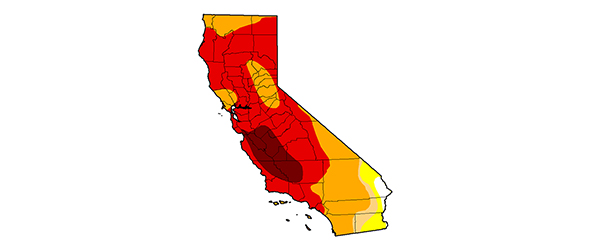

For the last decade, however, a persistent drought has hung over southern New Mexico and much of the U.S. Southwest. The snowpack in the Rocky Mountains, which feeds many of the region’s rivers, has been thin, and the ground dry.

Only once in those years, in 2008, did the district’s farmers receive a normal irrigation allocation. The last two years have been even worse, as a severe drought associated with the La Nina weather phenomenon cut water supplies even lower. The district’s allocation in 2011 was a mere 255 millimeters per hectare (4 inches per acre).

Two weeks ago, the district announced that this year would not be much better: only 383 millimeters (6 inches) of surface water.

Just upstream, the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District is in a similar position. It has warned farmers that they face a possible water shortage this summer.

The source of all the consternation is several hundred miles north, in the Colorado Rockies, where the snowpack that provides 80 percent of the Rio Grande’s flow holds less than half its typical water content. Elephant Butte reservoir is itself more than 80 percent empty.

“It’s pretty bleak,” said Gary Esslinger, the district’s treasurer-manager.

Bleak, that is, for surface water. Despite the scant runoff, most farmers in the EBID haven’t missed a beat. Esslinger told Circle of Blue that yields have been good, and, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture data, inflation-adjusted cash receipts for all crops in Doña Ana County have steadily increased over the decade.

The district’s economic health is largely due to record levels of withdrawals from the aquifers in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. The Office of the State Engineer, which oversees groundwater, announced that, because of the miniscule surface water allocation last year, groundwater pumping more than doubled compared to the two previous years.

Dipping Into Savings

The drought has certainly walloped surface water supplies, but policies and management downstream also have affected farmers in the EBID. Changes to the operating agreement for Elephant Butte reservoir in 2008 has meant that, in the years since, more water has been sent to irrigators in Texas.

And this year, farmers in Mexico requested their allocation on the regular timetable, beginning April 1. Farmers in the EBID had hoped to wait until later in the growing season, during peak demand, to use their surface water allocations. But because of the request from Mexico, the reservoir gates will now be opened more frequently, resulting in greater water losses, from both evaporation and from water soaking into the dry river bed.

-James Phillip King

New Mexico State University

So that means groundwater, that subterranean savings account, will be heavily drawn on again this year. Most farmers in the district have wells, and those who don’t will purchase water from neighbors or let their fields go fallow. Farmers with groundwater rights are allowed to apply 3.4 meters per hectare (4.5 feet per acre), surface water and groundwater combined. With a 383 millimeter (6-inch) surface allocation, almost 90 percent of the irrigation water will come from the aquifers.

Since 2006, the state has required groundwater withdrawals to be metered and reported. The aquifers are replenished by flows along the Rio Grande, by seepage in the canal system, and by water applied to fields that is not taken up by the crops. Late summer monsoons can also help, but they are erratic.

When dry years decrease the runoff and increase pumping, it is a “double whammy on the system,” said James Phillip King, a hydrology expert at New Mexico State University in nearby Las Cruces.

These two forces — low surface supply and constant demand — have “created an unsustainable situation for EBID farmers in the long term,” said the state engineer Scott Verhines, in a statement.

The Office of the State Engineer told Circle of Blue that, in the past several years, groundwater levels have dropped by 3 to 6 meters (10 to 20 feet) in two valleys that are part of the irrigation district. The office said it does not keep track of wells that have gone dry, but the staff has heard reports from farmers about wells not producing as much water as before, in addition to reports of increasing groundwater salinity.

The state has also requested groundwater pumping data from Texas, so that it can better understand the health of the aquifers — but Texas has not yet provided that information.

The irrigation district, meanwhile, is doing what it can to enhance the aquifer recharge rate. James Narvaez, the district’s hydrologist, said the monsoons can throw off a lot of water. To capture it, the district is using miles of drains and canals to slow down the runoff and to let it percolate into the ground.

Intensive groundwater pumping in the EBID began during a drought in the 1950s that ebbed in the early 1970s. Then, every year from 1979 to 2002, farmers received a full allocation of surface water. Now, groundwater is once again at the fore.

Esslinger, the district’s treasurer-manager, is hoping that the summer monsoon season brings some relief. “I look for anything positive,” he said.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!