Major Federal Study Sets Foundation for Colorado River Basin’s Future

Climate change and population growth will force the basin to add new supplies, harness demand, and change operational agreements, officials say.

Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

By 2060 seven western U.S. states face a “significant gap” between their water demands and the available supply from the Colorado River Basin, said Interior Secretary Ken Salazar during a press conference Wednesday to mark the release of the department’s three-year study of a critical watershed in which demand already exceeds supply.

The landmark study — the most comprehensive water study in the department’s history — revealed a “troubling trajectory,” Salazar said. The arid basin, which provides water to an area in which 40 million people live, will become drier, more densely populated and — even with new supply projects — more vulnerable in terms of water reliability, hydroelectric power generation, recreation, and river flows.

The median gap between supply and demand is 3.2 million acre-feet by 2060, or nearly 25 percent more than the forecasted annual flow when accounting for climate change, and most of the growth in demand will come from cities and industries.

“There is no one solution,” Salazar said. “We need to reduce demand and we need to consider increasing water supply through practical measures.”

The mix of solutions — and what makes one “practical” — is the most disputed section of the study. The Bureau of Reclamation, the lead agency, evaluated 30 options and slotted them into four “portfolios” based on water supply reliability, technical feasibility, and energy- and carbon-intensity.

–Kay Brothers

study co-manager

Excluding the projects with low reliability or tremendous technical challenges, the basin could increase its water supply by 7 million acre-feet by 2060 at an annual cost, in 2012 dollars, that ranges from $US 2 billion to $US 7 billion. Those cost estimates are quite uncertain and are best used as a relative figure to compare options, not as an absolute number for what the actual cost might be, said Carly Jerla, a study co-manager and an engineer with the Bureau of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado office.

The bureau did not rank the projects it evaluated or make recommendations. But considering the depth and sophistication of its analysis and its collaboration with the basin’s myriad interest groups, the study will set a foundation for all future discussions of water development in the Colorado River Basin.

A Call to Action

A handful of statistics show that the basin is already stressed. A drought that began in 1999 — the longest in the Southwest in the modern era — combined with unrelenting demand from water users have pummeled the basin’s two largest reservoirs. Lakes Mead and Powell have not been full in 13 years and now sit at just 52 percent of capacity.

These circumstances pushed average demand in the basin above the average annual supply in 2002, where it has remained.

The study makes clear that if climate change cuts into river flows as expected, doing nothing to increase supply, reduce demand, or change operational procedures leads to greatly increased vulnerability to water supply shortages for Las Vegas and for the four states that comprise the upper basin — Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. Based on climate modeling, the study forecasts an 8.7 percent decline in the river’s average annual flow, compared to the 1906-2007 period.

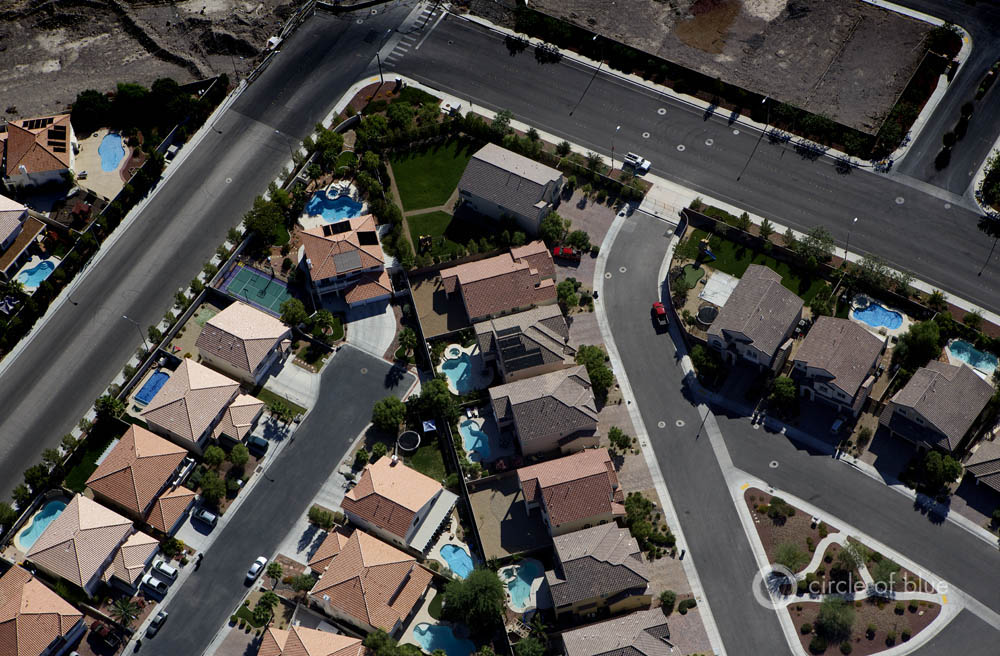

If no action is taken, by 2041 there is a one in five chance each subsequent year that the upper basin states would not be able to meet their water delivery obligations to the lower basin, according to the study. And nearly every other year Lake Mead would risk dropping below the lowest current intake that siphons drinking water to Las Vegas. (The city is building a third “straw” at a lower elevation as a hedge against this threat.)

“The upper basin is currently unprepared for this possibility,” said Eric Kuhn, general manager of the Colorado River District, which is in charge of developing Colorado’s portion of the river. “To address an uncertain future, upper basin users will need to develop new risk-management strategies including improved aggressive conservation, optimal use of storage and water-banking options.”

Not only will climate change reduce the amount of water available, rising temperatures and decreasing rainfall will also increase water demands, especially for irrigation. A 2010 Bureau of Reclamation study found that each 1 degree Fahrenheit (0.6 C) increase in temperature pushes up water demand in the basin by 5.5 percent; each 5 percent decrease in precipitation corresponds with a roughly 1 percent increase in water demand.

“The study gave us the tools,” Kay Brothers, a study co-manager and a consultant to the Southern Nevada Water Authority, told Circle of Blue. “The states need an integrated planning process now for further evaluation and studies.”

“We simply have to tackle this problem now so that our children and grandchildren will have water in the future,” said Anne Castle, the Interior Department’s assistant secretary for water and science.

What To Do?

The Bureau of Reclamation received more than 150 suggestions for how to close this gap. It winnowed those into 30 representative options to evaluate for the final report. These items range from desalination, weather modification and a Missouri River pipeline on the supply side, to conservation and wastewater reuse on the demand side. The bureau also looked at changes to reservoir operations, water markets and water banks to facilitate water transfers.

The most technically feasible options were placed into four portfolios. The bureau then estimated the cost of the projects and the cheapest order in which to deploy them. Those projects not selected for a portfolio are not likely to be considered in future plans by the states or the federal government, Jerla, the study co-manager, told Circle of Blue.

“I would be surprised if we see things like icebergs and water bags,” she said. “The things that got cut out of the portfolios — it’s hard to think those things will be considered going forward.”

Basin water users are already undertaking projects similar to those in the portfolios:

- Last month, the San Diego County Water Authority agreed to buy the entire output of a desalination plant planned for the southern California coast.

- Also last month, the U.S. and Mexican governments signed an agreement for the first time to share shortages and surpluses in the river’s lower basin.

- In 2004, Palo Verde Irrigation District and the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California signed a 35-year agreement to transfer water from farmers to cities.

- The Southern Nevada Water Authority has the rights to pump 84,000 acre-feet of water from groundwater basins in northern Nevada. It will build a 300-mile pipeline to deliver the water.

The big infrastructure projects will take years to plan, permit and construct — if they ever make it that far. In the near term, Brothers said, water conservation and reuse are promising solutions.

An emphasis on conservation would be cheered by many groups who rely on healthy river flows.

“We’re glad that conservation measures were included, and we hope they prioritize it,” said Molly Muggleston, project coordinator for Protect the Flows, a group that represents nearly 600 businesses in the basin, mostly in the recreation and tourism industry.

“We should do all we can in the name of conservation before we start building pipelines and drawing water from an area — the Midwest — that is already in drought,” Mugglestone told Circle of Blue. The study estimates that conservation could free up 2 million acre-feet from municipal, industrial and agricultural users.

One factor the study did not consider, according to Brothers, is the effect of higher prices on water demand. The cost of developing the new supplies assessed in the study is significantly higher than the water currently available. More expensive water would certainly result in lower consumption.

Explore: Colorado River near Las Vegas in pictures

Click through the photo gallery below to enlarge the images. Commentary accompanies each photograph.

Follow the photographer’s route.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Sir,I being a retired civil engineer, wants too highlight some points for your consideration. After studying the above articles I felt the learned authors (mostly) given their opinions by studying toposheets etc,for preliminary report.Mostly by negative approach. Detailed alternate surveys and proposals are to be studied by eminent field engineers NOT by economists. When we are wasting enormous quantity of precious water to sea we must feed the thirsty at any cost. The federal Govt must give freehand to USBR to supply water to parched lands, drinking water to the needy, I think the present Govt. will take up this issue on war footing,first completing the detailed ground survey,not classroom survey. PAV Narayana. Retd.Dy Chief Engineer,Govt of Andhra Pradesh, India. (Irrigation Dept). E mail- pydipati_v@yahoo.co.in