Making Connections in the Philippines: Water Privatization Across Manila’s East Zone

While water privatization projects around the globe continue to be controversial, Manila stands out for its innovations and its impasses, often touted as one of the world’s most extensive urban water privatization projects to date.

By Sarah Haughn

Special to Circle of Blue

MANILA, the Philippines — Streets, glistening with rainwater and the night’s refuse, bend and buckle through throngs of makeshift homes and crowded shops where families awaken and entrepreneurs vend sodas, spirits, and simmering stews. Roosters crow in anticipation of dawn.

Early risers peer from a window here, a doorway there. Preparing for their commutes to work in the city, they cluster, awaiting the sputter and hum of motorcycle taxis, the smoky fumes mingling with the spicy fragrances of early morning Pamatid Gutom, the food of the streets.

Enter the almost melodic cacophony of 3 a.m. in the community of Cuatro, an informal settlement located in the East Zone of densely populated and largely unplanned Metro Manila.

As night wanes, its lifting shadows illuminate a series of plastic pipes, vibrantly blue, edging along the same damp streets. The pipes lead to a water-filling station, where the community gathers to take advantage of clean, running water. In its third year of operation, the filling station provides safe drinking water twice daily, for an hour in the morning and another hour at night.

But it was not always this way. The pipes are relatively new, signs of Manila’s massive water privatization.

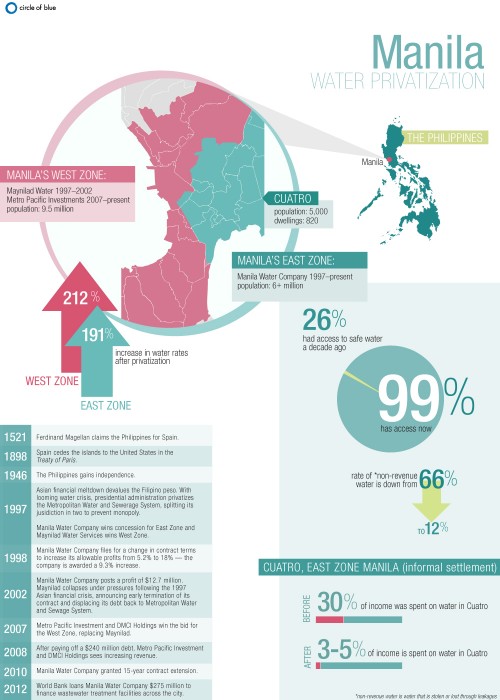

In the late 1990s, the Philippines — faced with mounting debt, debilitated public utilities, and an impending water crisis — privatized the capital city’s increasingly inefficient and corrupt water and sewer utility, which was servicing fewer than half of the East Zone’s inhabitants. Often touted as the world’s most extensive urban water privatization project to date, the transition of Metro Manila’s water utility from public to corporate hands stands out, both for its innovations and its impasses.

As of 2012, the East Zone, a region of now more than 6 million people serviced by Manila Water Company Inc., is one of the few metropolitan regions in the western Pacific to claim nearly 100 percent access to potable water for its residents. The improved access, however, is offset somewhat by a dramatic rise in cost — after privatization, water rates are 191 percent higher than rates charged by the public utility.

While this seems perhaps a paltry success to those with constant and affordable access, for the residents of Cuatro previously without access to publicly provided water, it is a significant improvement from when they paid an exorbitant 30 percent of their incomes to water pirates who patrolled the streets with large tanker trucks. Here in Cuatro, a better life — one in which families can afford not only food, but also medicine and education — begins with the community’s newly ubiquitous blue pipelines.

Through the Looking Glass, Half Full

People from more than 50 homes here in Cuatro gather each morning at a shared water station to collect enough to satisfy their needs until evening, when Cuatro’s second ration begins to flow.

Often among them is 11-year-old Omar, who lives with his aunt and uncle and who works the morning hours selling fresh mackerel to passersby in Lower Cuatro. The presence of piped water has made business for his boss — a fishmonger — more profitable, as people are now spending less time and money for their water and can afford to purchase higher quantities of nutritious food, like fish. Without his early morning job, Omar would probably be once again begging on the streets of downtown Manila. Now he goes to school when the fish are all sold.

This is very different from just over a decade ago, when only 26 percent of the 4.5 million people living in the East Zone had access to safe water, according to Manila Water Company, Inc., the private company that has provided connections since water became a private good in the Filipino capital.* Now, with more than 6 million people living in the East Zone, coverage is closer to 99 percent, estimates Robert Baffrey, department manager for wastewater operations at Manila Water.

“1997 was a water crisis,” Baffrey told Circle of Blue. “There was no funding, and infrastructure was poor. We brought in a long-term model: we provide service and infrastructure; we expect to recover our investment over a long period of time; if, for example, we spend $US 100 million, it is recovered over the entire 25-year concession period.”

Power and Water: Privatization of Two Industries and Creation of Two Government Offices

In 1946, after three centuries of Spanish colonization and 47 years of U.S. occupation, the Philippines achieved independence. In the following decades of transition, however, the nation struggled with devastating natural disasters. Typhoons, tsunamis, and earthquakes battered an already politically and financially unstable country.

Recipients of nine conditional loans, called Structural Adjustment Programs, from the World Bank, the economy of the Philippines was drastically restructured to favor privatization beginning in the 1960s. The shift created a climate friendly to private foreign investors.

Bolstered by the perceived success of the privatization of electricity from 1994 to 1998 by President Fidel Ramos, the administration decided to also privatize the struggling Metropolitan Water and Sewerage System (MWSS) in 1997. Following the Paris water privatization model in which the utility split its jurisdiction in two to prevent monopoly, MWSS granted Manila Water a concession for the East Zone and Maynilad Water Services, Inc. the West Zone concession.

The Ramos administration extensively campaigned the public, providing information about privatization and the bidding process to people both at the city level and nationally. Despite post-award allegations of unrealistically low-dive bidding — proposing unattainably high service for low cost, so as to win a contract, with hopes of improving the terms after winning — the bidding process stands out as one of the world’s most transparent because of its contract terms, as well as its balance between domestic and foreign interests.

Post-bid, however, the contractual checks and balances have not been as easily implemented. Both national and international civil society organizations and researchers have criticized the government for not being as diligent in defining the roles of its regulatory office and its office of administrative appeals — two government offices, created to function as the government’s way of maintaining the public’s stake in this newly privatized venture — as it had been in administering the bidding process.

Following the severe financial collapse in 1997 and the failure of Maynilad in the West Zone in 2002, a lengthy legal dispute over contract controversies and rates increases ensued. The dispute, for some, has overshadowed the benefits of water privatization in the Philippine capital. Yet, For others, even considering the obstacles, the privatization of water has been largely beneficial, especially when set in contrast with the many failed attempts around the world.

Pros and Cons After 15 Years of Privatization

Though Manila Water failed to meet its contractual target of full coverage by 2006, their water coverage statistics speak loudly and imply success.

“Providing water to areas, especially for the less privileged, does a lot on the large scale for the economy and for the livelihood of people in Metro Manila,” Baffrey said.

Despite a looming water crisis and the Asian financial meltdown of 1997 — which almost instantly devalued national currency in the Philippines and elsewhere across Asia, in addition to incapacitating potential investors — Manila Water managed to tremendously increase water coverage in the East Zone to 94 percent in less than a decade. Achieving another 5 percent from 2006 to 2012, the company continues in good terms with its investors and recently garnered an extension of its contract through 2037, as well as a $US 275 million loan from the World Bank to finance wastewater treatment facilities.

Manila Water’s success in communities like Cuatro is largely due to grassroots, community-based delivery schemes, where large subsidies are granted to low-income residents who are then responsible for their own infrastructure and management.

“This is our lifeline rate,” Baffrey said. “It represents the basic consumption for a household to live, the basic survival. Charges go up with additional use above the lifeline survival rate. Our commercial connections are considered money-making, so the rates are higher. We don’t vary charges on geography, but on use.”

Communities receiving the lifeline rate — which Manila Water defines as 10 liters (2.6 gallons) per day per household, costing about 3,000 pesos, or $US 70 annually — are, in turn, obligated to supply their own piping infrastructure and individual hook-ups or filling stations, as well as to administer their own metering.

For instance, Manila Water supplies the water connections for communities in the East Zone, but it is left up to the residents of each community to install the bright blue pipes that line the streets and alleys. In the case of Cuatro, installation and distribution are in collaboration with Kids International Ministries, an education, water, and sanitation advocacy mission.

Manila Water has reduced non-revenue water — water either illegally siphoned or lost through leakages — from 66 percent to 12 percent in the East Zone, according to Baffrey. Much of this was largely due to illegal connections in informal settlements, he said. Using everything from technical solutions to partnerships with local communities, the company encourages grassroots management.

“In informal settlements, we partner with strong leaders. We provide them with the bulk connection, then community administration takes over to set pipe articulation and metering after that point,” Baffrey said, explaining how this technique to reduce non-revenue water gives the community itself ownership in the water. “There is more accountability — if there are leaks, the community pays for it.”

The improved access, however, is set in contrast to the dramatic rise in cost for the people of Manila — water rates in the East Zone are 191 percent higher and in the West Zone 212 percent higher now than before privatization. In many cases, especially within poorer communities with shared connections, “access” often means the water runs once or twice a day for just an hour or two.

Still, some advocates say, people who once paid an exorbitant portion of their income for water from private trucks now pay significantly less for piped water.

“Water is the most important thing,” according to educator, relief worker, and missionary Jeff Long, who founded Kids International Ministries and has lived with his family in the impoverished communities of Manila’s East Zone for two decades.

While standing at the top of Cuatro’s gentle hillside where shops were opening for the morning, Long said that, before the water stations were built, people were spending 30 percent of their meager incomes buying water. Now, because of the water stations, only 3 percent to 5 percent of their incomes.

“These people are able to buy their food now with what used to buy their water; they can buy medicine or help educate their kids,” Long said. “So just having clean water stations in [Cuatro] for 5,000 people — 820 dwellings — is huge as far as their daily lives and the way they can exist on meager incomes.”

Treading Water: Resource Privatization’s Uncertain Future

Across the globe, water privatization continues to be a controversial process. Its results remain intricately tied to country-specific economic climates, often shaped by colonial and post-colonial legacies of power and resource distribution, as well as cultural beliefs about whether water is a public or private good.

Stemming from a line of failed water privatization projects in other parts of the world, some fear that private systems place the risk of failure on the public the uses the services, not the companies that provide them and profit from them.

Even the most optimistic of privatization projects in the past — such as those in Jakarta, Indonesia, and La Paz, Bolivia — initially appeared successful. But high rates and expensive hookups, as well as questions of the constitutionality of including private sector agendas in public legislation, have led to public unrest, forcing each respective government to also address the failures of its model.

In most cases, as long as the venture remains profitable, private operators continue to seek extensions of their contracts. Yet, customers and water experts alike wonder what happens if profits dwindle, and private contractors hand hand a broken system back to the government.

This happened in Manila’s West Zone when, in February 2002, Maynilad — a partnership of Benpres Holdings Corporation, Suez, and the Lopez Group — collapsed under pressures following the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Maynilad announced the early termination of its contract, displacing its debt back to the public utility, Manila Water and Sewer Services (MWSS).

In the original bid, Maynilad had inherited between 80 to 90 percent of MWSS’s debt burden, compared to Manila Water’s 10 to 20 percent. As the peso dropped in value, Maynilad’s payments on loans doubled in pesos per dollar. Weak revenues and increased debt made it impossible to secure loans. Maynilad’s financial emergency worsened further, because the city’s privatization approach relied heavily upon expensive foreign consultants with little knowledge of water infrastructure.

After receiving Maynilad’s termination, the MWSS re-bid the West Zone. Metro Pacific Investment and DMCI Holdings won the bid for Maynilad’s 85 percent equity stake in 2007. After paying off a $US 240 million debt, the new company saw increasing revenue in 2008.

While the Maynilad crisis leaves Manila’s citizens evidence to doubt privatization, Manila Water interprets the operational risk of the public-to-private relationship differently.

“Our model is unique,” Baffrey pointed out. “It is one of the few successful partnerships in the world in terms of service and overall synergy with the regulatory body. You have a progressive regulatory framework that allows for flexibility to provide service as needed. Combine that with Manila Water’s willingness to take risks and get service up.”

This ambitious approach sets Manila Water apart from the criticism over the city’s privatization in general — while there exists ample criticism from resource experts and water rights advocates concerning the commodification of Manila’s water, very few point critically to Manila Water Company alone.

Long’s experience in informal communities in the East Zone, however, affords him a healthy skepticism.

“People are very resilient,” he remarked. “They have earthquakes, typhoons, flooding — amazing, amazing tragedies happen in their lives, and yet they keep bouncing back. They are very resilient people; they’re just not given a chance to work and to thrive, because the people who have it all continue to find loopholes and develop those loopholes.”

Long said that big businesses do not trust or get involved with lower-income communities who lack a partnering organization like Kids International Ministries.

“If we are not willing to sign on the dotted line, then they are not going to send water into an impoverished community,” he said. “They would not believe or trust that [the residents themselves] would actually manage it properly and pay the bill. So without our signature and without our willingness to set up the infrastructure, they would not do it.”

Still, the difference is evident here in Cuatro, where Kids International Ministries did partner with local residents who otherwise would not have had much negotiating power. And, according to Baffrey, the successes are two-fold.

“There’s an economic side to giving water as well, apart from the socially responsible part of being able to help these people survive,” Baffrey said. “There’s a health aspect, which leads to them being able to go to their jobs being sick less often. Not having to go out and pay more for water means, instead of spending time to get water, they can spend time doing things that can actually benefit their families.”

As the horizon unfolds and the heaviness of a hot day begins to settle, Cuatro motorcycle taxis shuttle their passengers toward urban Manila. Young Omar places the last mackerel on the scale, hoping for one final sale of the day so that he can leave for school. No longer dependent on costly water trucks, his morning customers now have more income to put toward food, medicine, and education, as do his own aunt and uncle.

Sarah Haughn is a contributor to Circle of Blue where she was a reporter in 2008 and 2009. J. Carl Ganter, Circle of Blue’s Traverse City-based co-founder and director, visited Manila last September. Amanda Northrop is an undergraduate student at Grand Valley State University and a Traverse City-based design intern for Circle of Blue. Reach them at circleofblue.org/contact.

*Initially owned by The Ayala Corporation, International Water Limited (Bechtel), United Utilities, and Mitsubishi Corporation, Manila Water Company, Inc. is currently under the majority ownership of The Ayala Corporation. Mitsubishi, the International Finance Corporation, and the public also own shares.

Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!