New EPA Guidance for Combined Sewers Draws Mixed Reviews

Seattle will be the first city to test the new integrated framework.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

At a U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee hearing on July 25, a panel of water managers and local government officials said that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s new framework for stormwater and sewage projects is a necessary reform, but it does not go far enough in limiting costs for communities that are struggling financially.

“The only substantive relief provided by the framework is scheduling,” said David Berger, mayor of Lima, Ohio. “It allows cities to prioritize cost-effective actions, but low-priority, low-benefit actions appear still to be mandated at a later date.”

Nearly two decades ago, the EPA introduced a policy for controlling municipal sewer overflows from pipes that carry both stormwater and sewage. The policy has proven to be chokingly expensive for cities, utilities, and their ratepayers. Many utilities have spent billions of dollars to build pipelines and subterranean holding tanks, as well as to expand treatment capacity.

Last summer, for instance, the Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District signed a record $US 4.7 billion Clean Water Act settlement to reduce the amount of raw sewage and polluted surface runoff entering local waterways. Since 1998, more than 40 communities have signed similar agreements with the EPA.

But because of the cost of these agreements — and the realization that other pollution-control projects might result in greater benefits — last fall, the EPA began taking public comments on a new strategy, called an integrated planning framework.

This is the administration’s way for communities to take a broader look at clean water.” — Katherine Baer,

American Rivers

In June, the agency released the final version of the strategy, which seeks to give communities more flexibility in meeting water-quality goals. The voluntary process also encourages use of green infrastructure, or natural water-absorbing systems such as wetlands and grass roofs that could cut compliance costs in the long run.

The water-quality requirements of the Clean Water Act are still paramount, but the integrated framework allows a city choose the sequence in which it will take on projects.

“This is the administration’s way for communities to take a broader look at clean water, said Katherine Baer, director of the Clean Water Program for American Rivers, a conservation group, in a phone interview with Circle of Blue. “This is about finding smarter, more cost-effective ways to meet existing standards.”

This Or That? Or Both?

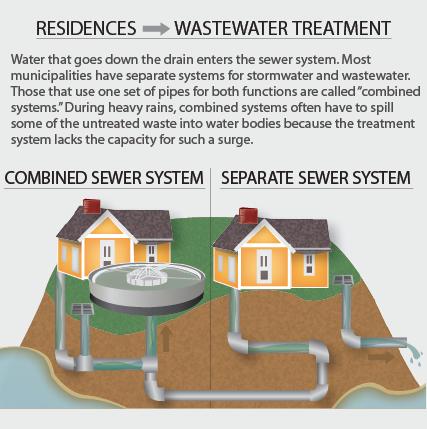

The cause of all this fuss is the “combined” sewer. Roughly 772 communities are served by these combined systems, in which stormwater and sewage flow into the same pipes. Heavy rains will periodically overwhelm a combined system’s flow capacity and force a utility to dump raw sewage along with surface runoff that can be laced with oils, grime, and chemicals into water bodies.

The EPA press office did not respond to Circle of Blue’s request for an interview on how the integrated planning framework was developed and how it would be implemented; rather, the press office provided a statement that basically re-stated the framework’s main points. People working for local water agencies, however, were willing to discuss the framework’s strengths and weaknesses.

Mark Pestrella, the assistant director of the Los Angeles County Department of Public Works, told Circle of Blue that the EPA is making a good attempt at recognizing that water is managed by many agencies, but the framework falls short of truly integrated water resources management.

“The EPA is saying, ‘You can take an integrated approach, but only to look at the two regulatory areas that we deal with,'” said Pestrella, who is also the stormwater committee co-chair for the National Association of Flood and Stormwater Management Agencies. Pestrella explained that a good case in point is water supply, which is a bigger problem for cities in Southern California and the Southwest, and which is not included in the new guidance.

Because the framework is written with such general language, Pestrella said that taking on the challenge of developing an integrated plan might prove too daunting for small communities which do not have the money, the technical expertise, or the political will that big cities do.

Baer, of American Rivers, echoed this latter point, as did George Hawkins, the general manager of the District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority, who was a witness at the House hearing last week.

“There are many jurisdictions that do not have the capability even to get to the negotiating table,” Hawkins said, because of the level of research and analysis that is necessary to evaluate an integrated plan. His agency spent $US 2 million on preparatory work before even sitting down with the EPA.

We’re not talking marginally better projects. We’re talking 20, 30, or 40 times the pollutant removal, compared to the combined sewers.” — Nancy Ahern,

Seattle Public Utilities

Many water managers, both at the hearing and in conversations with Circle of Blue, said that the framework does little to control costs, especially if all the framework does is shuffle the construction line-up.

Nancy Stoner, the EPA’s top water official, told the House subcommittee that the new guidance is not as rigid as is commonly assumed.

“Certainly needs are great,” she said. “But we think we have the flexibility now, under the framework, to address [cost concerns] as best as we can, in partnership with state and local communities using the resources available.”

Emerald Standard

Seattle, however, does have those resources. The largest U.S. city in the Pacific Northwest is one of the few large American cities without a consent agreement with the EPA for combined sewer overflows. Because those negotiations are now underway, Seattle will be the first U.S. city to find out how the new policy works in practice.

In May, Seattle officials announced a proposed agreement with federal and state regulators that will allow sewage and stormwater projects to be managed in tandem. The city, which expects to spend $US 500 million on capital infrastructure to implement the agreement, will submit a draft integrated plan by the end of 2014.

Since 1968, Seattle has spent $US 524 million (measured in 2009 dollars) to control overflows from combined sewers. This has reduced the annual polluted discharge by 75 billion liters (20 billion gallons), yet the city is still not in compliance. Nancy Ahern, a deputy director at Seattle Public Utilities, told Circle of Blue that the utility is trying to find the highest-priority stormwater projects to swap places in the timetable with combined sewer projects.

It may turn out that more cost-effective solutions are developed over time. Those less important requirements may be easier to meet down the road.” — Ben Grumbles,

Clean Water America Alliance

“We’re not talking marginally better projects,” Ahern said. “We’re talking 20, 30, or 40 times the pollutant removal, compared to the combined sewers.”

Even though the city will still have to meet the state standard of one sewer overflow per outfall per year by 2025, delaying the less beneficial projects is a smart move, says Ben Grumbles, who was an EPA assistant administrator for water from 2003 to 2008. He is now the president of the non-profit Clean Water America Alliance.

“It may turn out,” Grumbles told Circle of Blue, “that more cost-effective solutions are developed over time. Those less important requirements may be easier to meet down the road.”

Meanwhile, many eyes will turn to the Pacific Northwest, to see what an integrated plan looks like, how it is implemented, and whether it can deliver the benefits promised.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Many older cities have combined sewage collection systems and because sewage treatment plants have hydraulic limitations, they also have CSO’s (Combined Sewer Overflows) where, during larger rain storms, sewage diluted with storm water is discharged directly into open waters. Assuming that rain water was clean, many newer cities have separate sewage collection system and thus have no CSO’s, as all storm water is discharged directly into open waters. Since nitrogenous (urine and protein) waste in sewage is not required to be treated under the Clean Water Act (CWA) most sewage treatment plants lack the capability to treat this waste, while this waste (now called nutrients) is partly responsible for the excessive alga growth, causing dead zones, but presently mostly blamed on the runoffs from cities and farms.

Faced with this conditions, cities now will have to take measures to reduce water pollution caused by its storm water (new treatment for nutrients) and the building of additional nutrient treatment in their existing sewage treatment plants, while cities with combined systems also will have also close their CSO’s, often by converting their combined systems into separate systems, all of course at horrendous cost to the public.

When total load (carbonaceous and nitrogenous waste) analysis on the open waters, after proper testing, is made, it will show that cities with combined sewage collection systems actually are already better for the environment than separate systems, while all cities still have to address the pollution caused by the ‘nutrient’ waste in storm water and sewage.

Most people will assume that the major cost will be focused on treating this nitrogenous waste by the modifications required in existing treatment facilities, but do not realize the enormous cost of converting a combined system into a separate system.

Any honest cost analysis would show that, in order to meet all the needed conditions in cities with combined systems, it would be better for the environment and financial less expensive, to keep their combined sewage collection system, close of their CSO’s and built a brand new sewage treatment plant that not only will be able to treat the nitrogenous waste, but also can handle the large hydraulic load conditions. Some will claim that such treatment does not exist, but EPA already in 1978 in one of their reports acknowledged that such treatment was not only already was available, but actually could be built and operated at much lower cost, compared to conventional system, that are based on a century old treatment technology solely developed to control odors, hence incapable to treat nitrogenous waste.

EPA in 1983 also admitted that nitrogenous waste in sewage was ignored because it used an essential water pollution test incorrect, but sadly never corrected the test, while it in 1987, of the record, admitted that this test and thus regulations (that are based on the test) should be corrected. EPA, however, at the same time also claimed that this would be impossible as it would require a re-education and even retooling of an entire industry. An industry that is happy with the status quo, as nobody can be held accountable, while looking forward to built all these new public works projects required to meet the new requirements.