U.S. Supreme Court Navigates Waters of Ownership, Clarifies Possession of Missouri River Bottomland

Montana may have lost a portion of the bottom, but the state was awarded — and entrusted — all that floats to the top as part of its public trust authority to protect water resources.

By James Olson

Special to Circle of Blue

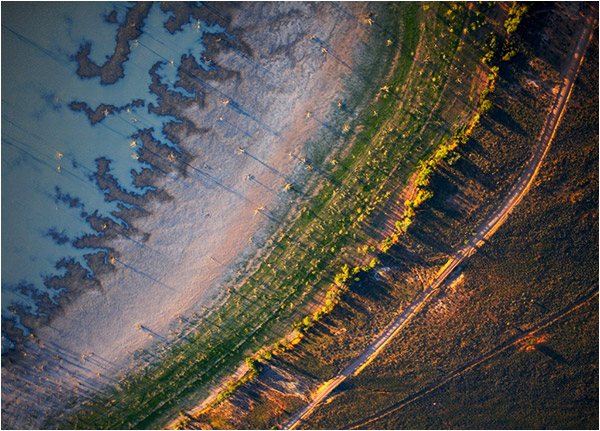

The 16-kilometer (10-mile) stretch of the Missouri River where it passes Great Falls, Montana, was once so swift, roiling, and precipitous that, in 1805, the Lewis and Clark expedition spent 11 days hauling equipment and boats on an overland portage to continue their transcontinental journey.

Earlier this year, the same fast-flowing reach again came to national attention, when the United States Supreme Court unanimously clarified the ownership of the riverbed beneath the Missouri and two other Montana rivers, the Madison and the Clark Fork.

In February’s 9-to-0 ruling — which overturned a previous decision by the Montana Supreme Court from March 2010 — the high court also asserted, emphatically, that states have the authority to protect the public’s use and enjoyment of rivers, regardless of who owns the bottom. In doing so, the U.S. Supreme Court confirmed a state’s authority to implement and enforce river safeguards to prevent interference with public use and environmental harms.

The case, PPL Montana, LLC v. Montana, tested Montana’s authority to require PPL Montana, a utility that operates hydroelectric dams on the Missouri, Madison, and Clark Fork rivers, to pay $US 41 million to the state to “rent” the river bottom that the state had contended that it owned.

The utility countered that Montana was not due the rents, because the stretches of river where the dams operate are not owned by the state, but by the utility. In its argument, PPL referenced federal law, whereby ownership of submerged lands depends upon navigability of a river at the time of statehood, or 1889 in the case of Montana. Under the “equal footing” doctrine of the Constitution, states are deemed to have title to the beds of navigable rivers within their borders.

The test for navigability is whether, at the time of statehood, a river was in fact navigable or susceptible to being made navigable; if it were not, then riverbed title remained at the federal level in the United States, until it were sold or granted with the adjacent land.

In other words, PPL was contending, and the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately agreed, that the utility owned the riverbeds in the sections in which it operated, because these sections were not navigable when Montana became a state in 1889 — a view confirmed by reports in the 1805 journals of Lewis and Clark, who had needed to portage.

However, the justices made special note that, though the state did not own the river bottoms, it did, in fact, own the water that flowed above and therefore was entrusted to ensure that this resource be protected for the public. What might, at first glance, appear to be a loss for Montana has actually set a precedent to protect water as a public trust in the United States during an age when water is increasingly being viewed as a commodity.

Long History of River Use

In a world that prizes energy and recreation, it is not surprising that the economic value of the Missouri would eventually collide with the demands for hydroelectric power. The decision in the PPL case takes into account the long history of settlement along the Missouri River in Montana.

Shortly after statehood, hydro-barons seized stretches of land along the Missouri with 9-, 12-, and 24-meter (30-, 40-, and 80-foot) waterfalls for dams to generate electrical power. Today, PPL operates 10 dams in Montana, and there is little historical evidence that the state had objected to the dams or claimed title to the riverbeds.

But in 2003, a group of parents filed a lawsuit in a Montana federal district court on behalf of their children. Looking for funds, they argued that PPL’s dams sat on riverbeds that belonged to Montana, as part of the state’s “school trust lands” that had been granted after statehood. The state almost immediately joined the suit, claiming title to the riverbeds under a legal principle known as the “equal footing” doctrine, and the state demanded back rents of $US 41 million from PPL for its use of the riverbeds from 2000 to 2007 (but did not mention rent going forward, leaving that for another day).

The federal district court dismissed the suit for lack of jurisdiction over the state’s claimed title to the riverbeds where the dams operate. As a preemptive strike, PPL then sued Montana in a state trial court. The utility was hoping to bar Montana from collecting its claim for back rent, but the state counter-sued, again arguing that it owned the riverbeds and demanding the rent.

The state trial court ruled in favor of Montana and awarded the state $US 41 million back rent.

PPL appealed to the Montana Supreme Court, which in March 2010 agreed with the lower court and ruled that the state owned the title and should get the back rents. But, two years later, the U.S. Supreme Court overruled that the lower courts had used an incorrect test for determining navigability at the time of statehood.

Riverbeds Are Significant

It is critical to note that ownership of the bed of a river is not inconsequential. It is one thing to own land next to a river and enjoy use of its water for domestic, farming, or commercial purposes. It is quite another to own the land under a river’s flowing waters, where you can construct dams, mine minerals, or drill for oil and gas for profits that far exceed using the water merely to benefit the land that is adjacent to the river.

On the other hand, lack of state ownership of the land under the river could impair access to stretches of river now used by the public under paramount right for fishing, recreation, and tourism.

The nub is: how are waters deemed “navigable” under the “equal footing” doctrine to determine whether a state has title to a riverbed? Under the law, if the condition of the rivers would not have been navigable for travel, trade, or commerce at the time that the state joined the Union, title to the riverbeds would have remained in the federal government or private persons who had acquired title, traceable to federal ownership.

Viewing an entire river as a navigable unit where travel continued above or below impassable sections, Montana argued that short, non-navigable segments of an otherwise navigable river did not defeat state title of riverbeds in the non-navigable segments. The state’s reasoning was that, though there may be impassible stretches — like cataracts, waterfalls, and foaming rapids — there existed a more than significant stretch of these rivers that had a history of absolutely no portages or perhaps only long portages around the stretch, but continued commerce on the river above and below the obstructions.

The State Supreme Court agreed, and, as a result, the Madison, Missouri, and Clark Fork rivers were determined to be navigable at the time of statehood. Thus, in March 2010, the riverbeds of modern-day Montana belonged to the state and were held in public trust for citizens for posterity.

“Navigability” Does Not Include Waterfalls and Rapids

But the U.S. Supreme Court overruled the State Supreme Court decision just two years later, saying that an incorrect test for determining navigability had been used. The correct test, according to the U.S. Supreme Court, is instead to look at each segment of a river, including where PPL operates hydropower facilities.

In the end, this final decision gave riverbed title to the utility where it operated its dams, since it had acquired the land alongside the rivers when they had passed from the federal domain into private hands. The water of the rivers, however, was left to the state.

Presciently, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in PPL Montana, LLC v. Montana also recognized that public trust principles are an important part of the residual sovereign power of states to protect their water and other historically recognized commons like air and wildlife.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision may have narrowed state ownership of riverbeds, but it has also reinvigorated the public trust doctrine as a fundamental basis for states and citizens to insist that their rights and sovereign power to protect water and other public natural resources, and their public use, within their borders cannot be overtaken by private interests or be overwhelmed by harms.

James Olson is a Traverse City-based attorney who specializes in water and environmental law. Olson chairs Flow for Water, a Michigan-based nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving the commons and the public trust doctrine of water and public natural resources.

Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

I agree that the “public trust” doctrine should help protect water and other public natural resources. However “public use” of non-navigable streams goes too far.

If water alone establishes public use rights, why not snow? Drainage ditches? Or the morning dew?

The US needs to stop attaching “public use” to natural resource protection laws. Unfettered access does not preserve our waters, especially the smaller sensitive streams.