Report: Market-based Programs for Watershed Improvement Double Globally

China is the world leader for watershed payment programs. But in other regions, long-term funding and monitoring are challenges.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Direct payments to property owners who, in turn, change their land use behavior is an increasingly popular method of improving water quality. Especially since this can often be done at a lower cost than through regulation or large engineering projects.

Such market-based programs have become so popular, in fact, as to have doubled globally since 2008, according to a new report from Ecosystem Marketplace, a nonprofit group focused on environmental markets and the benefits they bring.

The report identified 205 active payment programs operating in 29 countries in 2011, up from 103 programs three years earlier. (An additional 73 programs are being developed but are not yet running.) More than $US 8 billion was spent on watershed services in 2011, an increase of $US 2 billion over 2008.

“We truly mapped a set of projects and initiatives that hadn’t been mapped before,” Katherine Hamilton, a co-author of the report and the director of Ecosystem Marketplace, told Circle of Blue. “The space is new, and new programs are coming into being.”

How It Works

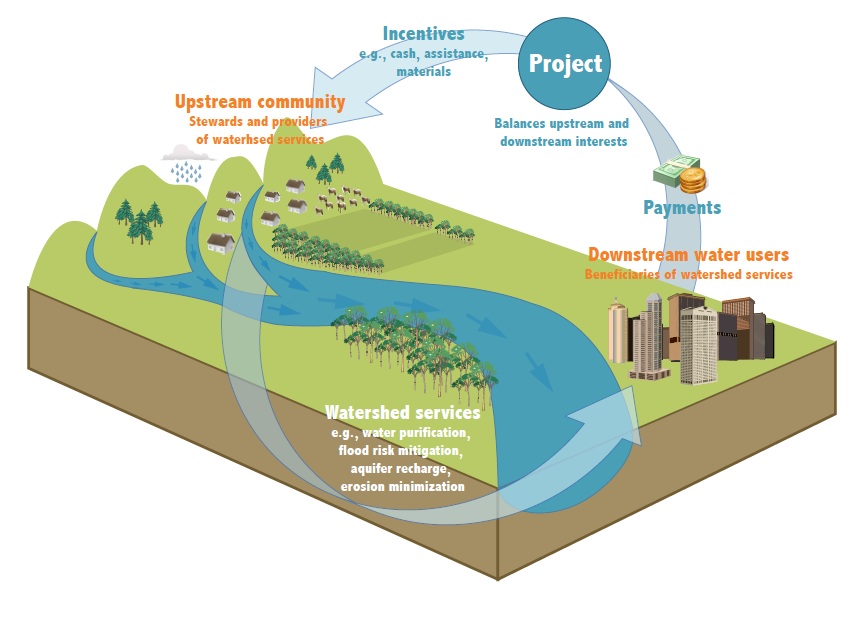

Payment programs come in many flavors. Ecosystem Marketplace grouped them into four broad categories. The most common is the “bilateral agreement,” in which a downstream city or business will “buy” water quality improvements by paying an upstream property owner or city for better land management or pollution control.

A second model lumps contributions from interested parties into a water fund, which then uses the money to invest in programs; these are most popular in Latin America.

The other two types – water-quality trading and in-stream buybacks – rely on existing regulatory programs to set limits on pollution or require well-defined property rights that allow for the transfer of specific volumes of water. So far the buybacks, generally used to keep water in a river, have taken place only in Australia and the United States, two countries with long-established water markets.

Where It’s Working

The projects highlighted in the report show the diverse ways to eliminate pollution and enrich lives. Some examples:

- In Kenya’s Lake Naivasha Basin, farmers receive vouchers that they can redeem for seeds or fertilizer, if they agree to manage their land better. The money, following the water fund model, comes from large-scale flower farms, ranchers, and tourism businesses around the lake.

- In China, the number of active programs doubled between 2006 and 2011. For the Min River Watershed Water Resource Protection Eco-compensation Program, Fuzhou, the 7.1-million-inhabitant capital of Fujian Province on China’s eastern coast, has a bilateral agreement with two upstream cities that protect the watershed by installing waste disposal facilities and controlling pollution.

- In Nepal’s Kulekhani Watershed, a hydroelectric plant uses money from government royalties to educate upstream villagers about better farming practices. The plant’s performance is hampered if too much sediment washes into the reservoir.

- In Zambia, the drinks giant SABMiller, the conservation group World Wide Fund for Nature, and the German development agency GIZ are paying to protect the water source for the city of Ndola, where an SABMiller subsidiary runs a brewery.

As was the case in the 2008 report, the size of government-run watershed payment programs in China skews the overall data. China, which featured payment programs in its most recent Five-Year Plan, accounts for 91 percent of the dollar value of the transactions that the report covers.

Befitting a country with serious concerns about its water resources, the Chinese government is one of many actors at all levels of government looking to market-based programs.

“Water is a massive issue, for quality and quantity,” Hamilton said. “Both the private sector and governments are seeking new ways to ensure water quality and availability. Market programs are one of many tools to ensure this fundamental need.”

Reed Watson, who studies environmental entrepreneurship at the Property and Environment Research Center in Montana, had a similar, simpler explanation for the growth of payment programs. “Economics, in a word,” he told Circle of Blue.

“Decision makers are starting to understand that the cost savings of natural resources protection are significant compared to built infrastructure,” Watson said, adding that time and transaction costs – the information and knowledge needed to write a successful contract – are the biggest barriers to broader acceptance.

But even those are starting to fall away as more programs come online.

“We might see a domino effect, once people build familiarity with the approach,” Watson said. “What works in the Catskills, for example, might not be effective in the Chesapeake Bay.”

These are non-traditional contracts, he added, so it is essential to figure out a way that the seller – generally the upstream party – can supply the water quality improvements that the buyer wants.

Why It’s Catching On

Often these programs are a way to clean up water bodies without adding regulations, as with voluntary payments from businesses or cities to farmers.

In other cases, though, regulations are necessary to lay the groundwork for transactions. For example, nutrient-trading programs in the United States, which set a cap on the amount of nitrogen or phosphorous in a river and let polluters buy and sell the right to pollute, rely on the Clean Water Act’s policy framework.

As with any fresh idea, payment programs see a lot of shifts as funding sources dry up or innovations burst forth. Many programs, in Africa and South America in particular, disappeared between 2008 and 2011, Hamilton said. On the other hand, she is looking forward to the benefits of new stormwater-trading schemes.

“There are a lot of new programs now,” Hamilton said. “The pace is picking up.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!