Mongolia Copper Mine at Oyu Tolgoi Tests Water Supply and Young Democracy

Mining boom in South Gobi influenced by local and global citizen activism

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

KHANBOGD, Mongolia – Though it is well before noon, the hot light of the South Gobi desert sun punches through the ventilation openings at the peak of Byambasuren’s white ger.

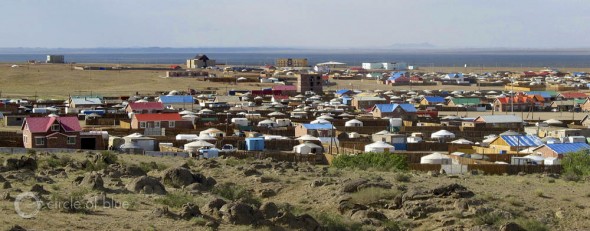

The door of her teepee-like home, a single round room built of felt and canvas, is open to a dirt compound surrounded by a fence made of rough-cut wood. Beyond that, cattle and horses churn a small grid of unpaved streets to powder. Herders on foot follow behind, their features obscure in yellow clouds of dust.

Byambasuren’s ger lies 700 kilometers (434 miles) from Ulaanbataar, Mongolia’s capital. The trip overland is mostly on hard-packed dirt roads and takes 15 hours across treeless steppes and sand. Much of the world’s second largest desert remains remote from the world, even forbidding.

That is not the case for Byambasuren, a young herder and mother, or for Khanbogd, an expanding livestock and desert town in Omnogovi, Mongolia’s largest province, which lies along the border with China.

Not far away, about 40 kilometers (25 miles) south, mining giant Rio Tinto and Mongolia’s young, free market government are developing one of the planet’s sizable reserves of copper and gold. The $6.6 billion, 80-square-kilometer (30-square-mile) Oyu Tolgoi mine is the largest industrial enterprise ever constructed in Mongolia, and, with 7,500 workers, the nation’s largest employer.

Along with the oil-producing tar sands mines in Alberta, Canada, Oyu Tolgoi also is among the most thoroughly scrutinized resource extraction projects on Earth. The reason: It’s located in one of the most water-starved regions of Mongolia.

Unlike earlier eras, when industrial companies descended on unwary countries to mine and log and drill with scant resistance, resource development in the 21st century faces new operating rules, many of them imposed by people like Byambasuren.

She and seven other herders, who have access to cell phones and the Internet, belong to Gobi Soil, a year-old environmental group. Byambasuren and her colleagues are the on-the-ground local hub of a national and global network of policy strategists, environmental scientists, and communications specialists that elevated Oyu Tolgoi and Mongolia’s capacity to manage its mining sector to the nation’s top political issue.

In June, Mongolians re-elected President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj of the Democratic Party, who campaigned on attracting foreign investment and strengthening environmental oversight of mining.

There are two big ecological issues. The first is preventing water pollution, principally in northern and central regions of the country caused by gold mining practices that use mercury and cyanide.

The second is sharing the South Gobi’s limited water supply between livestock herders and the country’s biggest hard rock and coal mines. “We need water,” Byambasuren, who like most Mongolians uses only one name, says through an interpreter. “Before Oyu Tolgoi came here, we had enough water for our animals. Now we don’t. Things are different.”

High Stakes, Major Players

Several big players, including Mongolia’s government, the World Bank and Rio Tinto, the world’s second largest mining firm, have a stake in the mine’s development. Rio Tinto, based in London, is well aware that its record of environmental management at a number of its mines is routinely criticized by prominent international environmental groups as abusive.

One example is the company’s big and closely scrutinized Grasberg copper and gold mine in West Papua, Indonesia, which it operates jointly with Freeport McMoran. The mine uses more than a billion gallons of water a month and unloads 230,000 metric tons of waste into the Ajkwa river daily, which kills plants and contaminates drinking water, according to Corporate Watch, a London-based investigative oversight group.

Among its many objectives, Oyu Tolgoi represents a new opportunity for Rio Tinto to introduce Mongolia and the world to state-of-the-art mining practices, including water use and recycling techniques that conserve water and limit pollution. The international mining sector, mindful of its global reputation, regularly commends Rio Tinto, which last year earned total revenue of US $55.6 billion, for responding to technological trends and heightened civic expectations here.

The Mongolian government, which owns slightly more than one third of Oyu Tolgoi, counts on the mine to finance its ascent to economic and political influence in Asia. The country’s newly elected Democratic Party leaders also want to prove they have the smarts and moxie to manage Mongolia’s mineral treasures and work as an equal partner with a global industrial giant.

The World Bank and its affiliated financial institutions, which helped to fund Oyu Tolgoi, weigh new loan requests to expand the mine against Rio Tinto’s record in the South Gobi in achieving the United Nation’s Millennium Development goals. And environmental and human rights organizations, with offices networked from Ulaanbataar to Beijing to New York to London, make a strong case that the Manhattan-size mine, tearing a big hole in the South Gobi, is producing permanent damage to land and water, and eroding the region’s irreplaceable culture of tiny human outposts, livestock herding, and seasonal wandering.

Oyu Tolgoi, in effect, is at the center of a globe-circling vortex of competing ambitions. It’s more than the mine’s location in a mineral rich and environmentally sensitive, water-scarce region or its immense dimensions. It’s more than the huge price tag and the mine’s prominent and stubborn developer. It’s more than a young government’s insistence on oversight and fair economic returns, or the substantial pressure from the world’s environmental community to restrain damage.

It’s all of these facets, mixed and modulated on a global motherboard, that have amplified Oyu Tolgoi into an internationally significant case study of the fierce and increasingly transparent civic conflict over tapping the earth’s natural resources.

Little more than a decade ago, this was territory so vacant it rivaled Antarctica, Siberia, and the Australian outback as places farthest removed from the global mainstream. Now there’s an airport outside Khanbogd. The money to be made here lures thousands of workers and attracts regular convoys of television producers, magazine writers, and documentary film crews.

Oyu Tolgoi’s executives are sensitive to the attention. “We are very aware of almost everything that’s said about this mine, wherever it comes from,” says Mark Newby, Oyu Tolgoi’s 42-year-old environmental manager, in an interview with Circle of Blue. “You have to listen. You have to respond. You can’t go eye to eye with the country or the community. A number of large mines worldwide did that, and they lost their mines as a result.”

‘Singing Well’ Sounds Alarm

Along the west wall of Byamba’s ger is a display cabinet with glass doors. Looseleaf notebooks, standing on end like encyclopedia volumes, occupy one shelf. They are sections of the mine’s environmental and social impact statement produced under contract for Rio Tinto.

Joining her are: Battsengel Lkhamdoorov, a 40-year-old herder who founded the Gobi Soil environmental group; Paul Robinson, a mining reclamation expert from New Mexico; and Batnasan Damdinsuren, a travel industry manager and interpreter who’s toured mining regions in Russia, Mongolia, and the United States.

Byamba rises from a stool at the center of a room that is getting steadily warmer and draws a binder from the case. It contains maps of the area with an assortment of red, blue, green, orange and pink dots. Each dot designates a well that supplies water to Oyu Tolgoi, or a well that monitors levels in underground water reserves close to the surface or 60 meters (180 feet) deep. The wells were drilled by Rio Tinto, or by Oyu Tolgoi’s previous managers, BHP and Ivanhoe Mines.

Byamba is particularly interested in one map with pink dots. She points to a well designated GHW4X6. “Here it is,” she says, “This is the problem.”

The day before, in a meeting in a local government office, Byamba told this story about the well. It is, she said, the “singing well” discovered by camels sometime in 2008 or 2009. She wasn’t sure. With their hooded eyes and dual humps, the big ungulates huddled day after day around a brown length of steel well casing, about eight inches in diameter, a foot tall, and open at the top.

Their behavior was so unusual, and so persistent, that some of Byamba’s neighbors rode into the desert on motorcycles and small trucks to investigate. The men didn’t see anything wrong with the pipe — no holes, no cracks. But when they dropped to their knees and put their ears to the well what came back wasn’t the drip, drip of a leak. What they heard was the unmistakable sound of a stream flowing deep underground. It was a cascade of water, startlingly loud in a land so dry that even when rain or snowmelt caused springs or streams to flow, it hardly made any sound at all.

“It was like bells ringing,” Byamba says. “It was a sound that you never forget.”

There are many places in southern Mongolia — a nation larger than Spain, France, Germany and Britain combined — where economic intent and water scarcity converge. None, though, illustrates the confrontation with more clarity or urgency than in Omnogovi, where Mongolia’s largest and thirstiest hard rock and coal mines are located. For several years Mongolia’s economy has grown more than 15 percent annually, faster than all but a handful of countries, largely due to the mineral exploration and development in this province so close to China’s steel and coal-fired power plants.

West of Oyu Tolgoi, hundreds of trucks loaded with coal from mines in and around Tsogttsetsii head to China on a two-year-old paved highway. In July, Oyu Tolgoi began its first shipments of copper concentrate to China. A 250-kilometer rail line (155 miles) from the Omnogovi mines to China is planned.

Omnogovi also is a place where domesticated camels outnumber people, where springs are rare, and rivers run intermittently. Just as gas prices in the United States serve as either a measure of national well being or a gauge of societal stress, water supply serves as a meter for uneasiness between Omnogovi herders and mining companies, and as a proxy for a range of other concerns.

The story of the singing well is illustrative. It was one of a group of production and monitoring wells drilled in 2003 by Ivanhoe Mines, a Canadian company, in anticipation of developing Oyu Tolgoi. Marked in white paint — GH4X6 — the well is surrounded by much older wells, dug by hand and no deeper than 20 feet, to tap what herders call “soil water,” the moisture stored closest to the surface and used to water livestock.

Byambasuren says she is one of the herders who were forced to reduce the number of animals they cared for because some of those hand-dug wells dried up. Nobody knew why until camels discovered the singing well. Byambasuren and her neighbors suspect the cascade they heard was soil water somehow pouring into the deeper aquifer and drying out their wells.

Robinson, a mining expert and research director at the Southwest Research and Information Center in Albuquerque, New Mexico, inspected the singing well and explains to Byamba that GHW4X6, as constructed, is different than what was described on the well’s technical document. “This picture shows only one pipe,” Robinson says. “The actual well has two. The second serves as an outer casing. What we saw is different than what’s shown here in important ways. This picture doesn’t show the outer ring.”

Robinson explains in English as Batnasan, who was raised in the South Gobi, translates for the two herders. Robinson concludes that the actual construction of the monitoring well is flawed. It was built with a sleeve of rock and gravel packed alongside the well’s steel casing that may be allowing soil water to drain from the surface to the deeper underground reservoir. “This is the low point,” he tells them. “It’s like a bathtub drain.” Robinson, an exacting professional, cautions that his view is a thesis based on his visual inspection and the document.

Mark Newby, the mine’s environmental manager, is well aware of GHW4X6. He says it is theoretically possible that it could drain the soil and shallow surface wells close to it. But that seems unlikely, he says. He says the company monitors the shallow wells in the area closest to GHW4X6, which was drilled before Rio Tinto took over the mine, and they aren’t losing water.

“We do acknowledge that the well wasn’t installed in the best manner possible,” Newby says. “But the effects that people think are going on wouldn’t be expected. And we haven’t seen anything like that in shallow wells.”

In September, Rio Tinto posted online a mass of new environmental studies that noted what it called “cascading behavior” in GHW4X6 and five other nearby wells, “indicating possible cross-connectivity of aquifers at these locations.” The new data pointed to a drainage problem with six wells that was stronger than Rio Tinto has acknowledged previously.

Regardless, in 2010, a year after Rio Tinto assumed primary management and ownership of Oyu Tolgoi, the company proposed pouring grout into GHW4X6 and the surrounding monitoring wells in a project to decommission the wellfield, he says. The regional government, which has jurisdiction for projects outside the mine’s perimeter, wouldn’t issue a permit for the work.

Instead, the local government turned to a citizen-government working group, which was established at the direction of the World Bank to oversee aspects of Oyu Tolgoi’s operations, including the decommissioning project, which still hasn’t happened.

The back and forth exemplifies most of the interactions between mine executives, local government officials, and herders. Newby asserts that Rio Tinto operates Oyu Tolgoi with exceptionally ambitious standards of water conservation, safety, and pollution prevention. Critics say the company can do much better.

A Contentious Project

Everything is an issue at Oyu Tolgoi. Robinson notes, for example, that Rio Tinto was late in preparing a mine reclamation plan to secure overburden and rock wastes during the mine’s operating life, and after Oyu Tolgoi closes. Rio Tinto finally introduced the plan in late September, years after the first ridges of mine spoils appeared at the edges of the open pit.

Herders complain that dirt roads constructed by the mine owners are barriers to their animals and cause excessive levels of dust. Oyu Tolgoi excutives say the issue is exaggerated. Rio Tinto is building a new 107-kilometer highway (66.5 miles) from the mine to the Chinese border. Company executives, mindful of the civic distress about dust, said in October that the first 80-kilometers of the new highway will be paved by the end of the year. The final 27 kilometers will be paved by the end of 2014.

Most significantly, herders worry that Oyu Tolgoi is draining the region’s water supply and making it difficult for their animals to find water. The steel fence that surrounds the gaping mine has blocked traditional herding corridors. Oyu Tolgoi also cut off a freshwater spring within the fenceline that herders used for generations.

The company substituted a manmade spring for the natural spring and installed it along the mine’s southern fenceline. Water bubbles from two pipes there, pools in mud, flows to a shallow pond, then vanishes into the dry sand of the Undai riverbed. Rio Tinto executives said the two pipes are temporary measures to keep water flowing past the mine’s boundaries so that livestock can drink. The project’s completion, they said, has been held up by local officials who want a review by the citizen committee.

On the afternoon that Robinson and two herders visit the artificial spring, they express skepticism that it will be as effective in watering livestock as the natural spring. “Just moving water to a new place won’t serve the need,” he says. “You can’t create a spring without the right geologic conditions. Oyu Tolgoi can’t just move water to a place that is convenient. They have to move the spring to a place that holds the water or it will become soil water, not surface water. “

Democracy Driving Growth

In the summer of 1990, as its Soviet neighbor to the north slowly collapsed, Mongolians held their first free election, a signal act that ended 70 years of socialist control. Almost nothing in this big country of surpassing vistas, a huge southern desert, and a treasure chest of mineral and energy resources has been the same in the 23 years since.

Skycranes hoist men and materials to the summits of new office towers in the capital city, where 1.4 million people live. The population of Ulaanbataar has nearly tripled since 1990 and is almost half of the national population of 2.9 million. Outside Ulaanbataar, across the green steppes, cell phones and solar panels connect and power the country’s rural herding families.

Visualizing Mongolia

Mongolian Population 2011

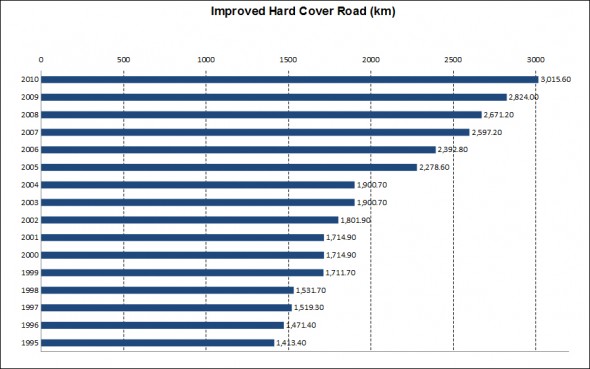

Surface Water Inventory (Rivers, Springs, Mineral Water, Lakes) 2007.

Number of Livestock (Horse, Camel, Cattle, Sheep, Goat) in Thousand Heads 2010.

As the U.S. and much of the developed West experience a damaging unraveling of institutional capacity and public confidence, Mongolia is ambitiously pursuing an economic development strategy that is founded in modern goals of environmental sustainability, income growth and nation building.

“We are a large country with a small population,” said Chuluunbat Orchibat, the 55-year-old deputy minister for economic development, in an interview with Circle of Blue. “Our economic goals are very high. We are working to improve the quality of life here. We also are trying hard to establish environmental standards that are high. We’ve had difficulties. But we know both can be done.”

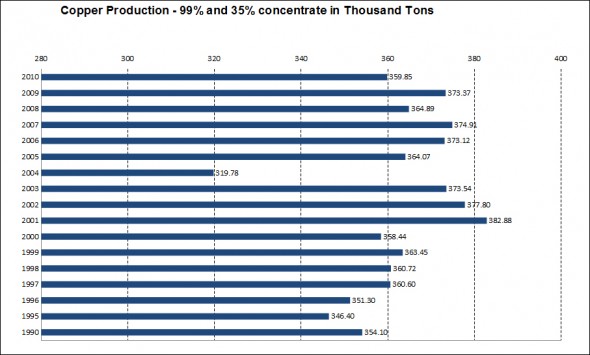

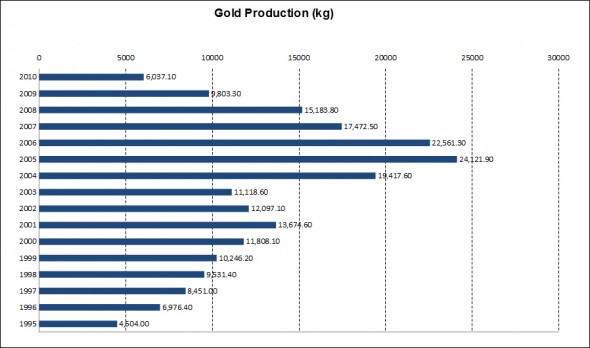

In interviews with herders and shopkeepers, activists and executives, Mongolians expressed similar views of the country’s potential. Two clear advantages make the economic formula possible: Copper, gold and coal lie beneath Mongolia’s South Gobi desert — hard rock and energy wealth that international mining companies are tapping; and Mongolia shares a border with China, the world’s largest processor and consumer of such materials.

There is, though, considerable skepticism among environmental specialists in and outside Mongolia that an economy dependent on mining can marshal the policymaking and enforcement apparatus to reach its environmental goals. Mining industry executives also are growing deeply suspicious of the Mongolian government’s ability to oversee their sector’s operations with consistency and fairness.

Just as in the other nations Circle of Blue has reported from in recent years — China, India, Qatar, Australia, and the western United States — some of the most significant issues center on water supply. The overriding concern: Can Mongolia safeguard its fresh water and grow the hard rock and coal mining sectors in a region of the country where water is in short supply?

“People care about this. Actually, young people are eager to make sure we have enough water. They want to protect the motherland,” said Bailgalimaa Nyamdawa, a 25-year-old lawyer at the Center for Human Rights and Development, a Ulaanbataar-based legal group that prosecutes civil cases against water polluters in the mining sector, most of which are owned by the Chinese.

“We need good regulations,” Nyamdawa said through an interpreter. “We need good enforcement. We need more people who know how to influence good policy. Before the mining started we didn’t have such problems.”

Growing Pains

In the first years after throwing off socialism in 1990, Mongolia’s rush to generate hard currency from mining was a familiar story of boom and pollution. While converting from a centralized economy to the free market, Mongolians suffered through dire seasons of food shortages, energy shortages, hunger and joblessness.

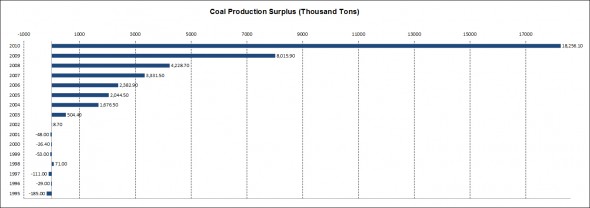

Desperate to generate revenue, Mongolia’s authorities in 1997 enacted the Mineral Law and opened most of the country to mineral development. More than 6,000 licenses were approved, including those for the big copper and coal mines in Omnogovi.

The first mineral mining boom occurred in northern and central Mongolia, where rivers and streams were colonized by gold miners and companies, many from Russia and China. They dropped backhoes and pumps into waterways, turned high pressure hoses on river banks, and used mercury and other toxic substances to separate gold from mud and sand. In short, they made a colossal mess.

Mongolians fought back at the grassroots. As a herding culture, Mongolians understood the ties between their well being and the health of water and land. Local non-profits allied themselves with international environmental organizations. Mongolia’s news media, aided by video and photographs taken by citizens and posted on the Internet, turned the damage into a national and international story.

In 2007, Tsetsegee Munkhbayar, a herder, was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize, a prestigious American public service award, for his work to organize opposition to mining pollution in the Onggi River, one of the country’s longest and largest.

Mining and environmental damage also became an election issue. In 2009, Mongolia enacted the Law on the Prohibition of Minerals Exploration in Water Basins and Forested Areas, which outlawed many forms of placer mining — the extraction of mineral deposits from streams, rivers and protected wild lands. In 2010, the government suspended almost 2,000 mining licenses and tightened provisions for securing licenses.

In 2011, Mongolia began to overhaul its mining law. In December 2012, the government circulated draft rules that alarmed industry executives. The new provisions called for higher financial returns for the Mongolian government and greater scrutiny of mining licensees.

The proposed regulations also offered greater security for water resources. The justification, say most industry executives and environmental authorities, is sound. Though smaller gold mining operations in the wet North and central regions led Mongolia’s mining boom in the first decade of the century, the country’s development authorities anticipate that the big and thirsty coal and hard rock mines in the South Gobi will generate the huge revenue streams, and employment, that will drive Mongolia’s economy.

Water Supply At Risk

Water supply is an impediment to increased mining. In 2010, the World Bank published a study of water use in Omnogovi and two neighboring South Gobi provinces. The study said that 3.8 million head of livestock consumed nearly 32,000 cubic meters (8.3 million gallons) of water daily. That was less than a fifth of the almost 100,000 cubic meters (26.4 million gallons) of water used daily by coal mines around Tsogttsetsii, and the nearly 70,000 cubic meters (18.5 million gallons) that was consumed daily by Oyu Tolgoi during its construction. At that rate of consumption, the bank estimated, the region’s groundwater supplies would last 10 to 12 years.

Rio Tinto reached different conclusions in its environmental studies. Oyu Tolgoi’s water source, explains Mark Newby, is an aquifer called Gunii Hooloi, near Khanbogd, that is 300 meters to 400 meters deep (1,000 to 1,300 feet). The aquifer was discovered by the Rio Tinto’s hydrologists and contains tens of billions of gallons of saline water, according to the company.

The Mongolian Water Authority permit allows Oyu Tolgoi to use 870 liters of water per second (20 million gallons daily), which is pumped to the surface and transported by pipeline 35 kilometers to serve mining operations. Newby says the mine recycles 80 percent of its water and uses under 500 liters per second (11.5 million gallons daily), far less than the permitted amount. Even at the higher permitted level of water use, he says, Oyu Tolgoi will consume about 20 percent of the water contained in Gunii Hooloi.

Rio Tinto’s study conservatively estimated that aquifers in the South Gobi were capable of supplying 500,000 cubic meters (132 million gallons) of water daily. A cubic meter is 264.4 gallons. That level of consumption, according to the company study, could be reached by 2020 as more mines open in the region, and more people arrive in Khanbogd and other towns to work and live.

Like the U.N. report, the Rio Tinto study concluded that water shortages are a barrier to mineral development in the South Gobi. The company study said “there may eventually be a need for the construction of water pipelines from the Kherlen or Orkhon rivers.” Those are two of Mongolia’s largest rivers and lie 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) away in the country’s forested North.

Proposals to pipe water from the North to the South have popped up periodiocally in Ulaanbataar since construction of Oyu Tolgoi began in earnest in 2009. But they aren’t generally taken seriously.

The cost of building and operating a lengthy water pipeline would be enormous. The Kherlen River flows into China, and Orkhon’s waters reach into Russia. Both countries would be expected to exert significant diplomatic opposition to such large water diversion projects.

What’s more, by the time water shortages become an emergency in the South Gobi, climate change may well have dried up enough of the nation’s surface water to significantly deplete the supply carried by the Kherlen and Orkhon rivers.

Climate Change Hotspot

A 2010 United Nations report found that since 1940, average annual temperatures in Mongolia increased 2.14 degrees Celsius (4.42 degrees Fahrenheit), a rate of increase that is higher than almost any other country. The number of droughts in Mongolia has increased 95 percent since 1950, and 680 rivers and 760 lakes have dried up since 2006, according to the U.N. study.

The drying trend is most pronounced in the South Gobi, according to the U.N. report. That’s also where the Oyu Tolgoi mine is located.

–United Nations Report, 2010

“In southern Mongolia, characterized by Gobi desert, the impact of climate change is expected to be extremely challenging,” according to the report. “It will be in the form of extreme events — sand and dust storms, flash floods or heavy snowfalls, droughts, desertification, land cover changes and water stress.”

In Ulaanbataar, Deputy Economic Minister Chuluunbat Ochirbat described the cross-cutting economic and environmental trends, unfolding in multiple dimensions, that confront his young nation. National ambition, he said, is expressing itself in new public pressure to gain more control of foreign industrial projects. The country’s mineral abundance can be developed with stricter environmental oversight and enforcement, which he said is occurring. But he acknowledged that the one big barrier that has not been adequately recognized or addressed is water scarcity.

“We’ve taken some actions,” Ochirbat said. “We suspended mining leases to control water pollution. We approved a new law four years ago to protect rivers and forests. I think what’s important right now is that our mentality has been upgraded. But we know we aren’t using our water resources properly.”

Tough Choices Ahead

Heading south to the Gobi Desert, and not far from Ulaanbataar, the sole paved two-lane highway dissolves into multiple hard-packed, single lane dirt roads. They criss-cross each other and from a distance resemble braided strands that rise to the peak of wind-tossed ridges and fall to treeless green valleys. Every now and again lone dirt roads peel off to the East or West, their destinations known to local residents and expert drivers who are familiar with the territory.

The multi-tracked roads, unique in the world, form a powerful metaphor for Mongolia’s national development. The sheer mass of unmarked roads that bound across the grasslands and desert reflect the fast-growing number of drivers and vehicles, and rising personal incomes fostered by a free market economy and just two decades of mineral development.

Multi-tracking also represents the complexity of Mongolia’s choices. Follow the tracks and eventually they lead to Khanbogd, a desert town that is both enthused about mineral development and concerned sufficiently about dust, water, and the durability of a generation’s old herding culture to support Gobi Soil, an activist citizens group.

The South Gobi is a frontier of economic development and a laboratory of environmental consequences and social responses. It’s the sort of place that attracts people like Sara Jackson, a young American who is a human geographer and doctoral candidate at York University in Toronto. Jackson has traveled often to the South Gobi to study the effect of Oyu Tolgoi on the region’s residents. “I spend time thinking about how people feel,” she said in an interview with Circle of Blue.

In preparing her dissertation, Jackson conducted 80 interviews and held five focus groups to understand how Mongolians in Ulaanbataar, Khanbogd, and several more communities perceive Oyu Tolgoi. The idea, she said, is to promote communication between stakeholders.

In a draft report she wrote earlier this year, Jackson found persistent distrust among the stakeholder groups: Citizens felt they were being ignored and Rio Tinto officials felt their work to support independent review groups at Oyu Tolgoi was not appreciated. Dust from new roads and a dwindling water supply are viewed by stakeholders as chronic problems that haven’t been addressed to the extent that residents feel their complaints produce actual results.

Jackson’s conclusion: “Without resolution of the issues discussed above, feelings of marginalization and exclusion will continue to cause local, regional, and national tensions about Oyu Tolgoi and mining development in general. However, mining has had the positive effect of politicizing citizens, who are now more aware of and active in local politics.”

“I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about what I learned in Mongolia,” Jackson added in the interview. ”Cautiously, what can be said is that what’s happening in the South Gobi is different than in other developing places. Oyu Tolgoi is a big target. They do get picked on more than other companies. But at the same time, if they are pushed that raises standards. And they are being pushed.”

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] and traffic poses a collision risk to herds. Boreholes built by Oyu Tolgoi may have accidentally connected shallow and deep water aquifers in the region, and may dramatically reduce the availability of shallow groundwater used for […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!