NASA’s GRACE Satellites Show Colorado River Basin’s Biggest Water Losses Are Groundwater (2005-2013)

During presentations this week at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union, researchers at the University of California, Irvine, announced that the region’s most visible signs of drought – shrinking reservoirs – are dwarfed by groundwater losses.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

As a first-ever declaration of water shortage in the Colorado River Basin approaches, water managers are paying keen attention to shrinking supplies in two bellwether reservoirs – Mead and Powell – which are both less than half full. But ongoing research from the University of California, Irvine, suggests that the bigger problem lies underfoot.

–Jay Famiglietti, director

UCI Center for Hydrologic Modeling

Surface water losses from the reservoirs are just a small part of the Basin’s overall water loss since 2005, said Jay Famiglietti, professor and director of UCI’s Center for Hydrologic Modeling.

“There’s that saying, ‘The fox is in the hen house’,” Famiglietti told Circle of Blue. “While no one is looking, groundwater is disappearing.”

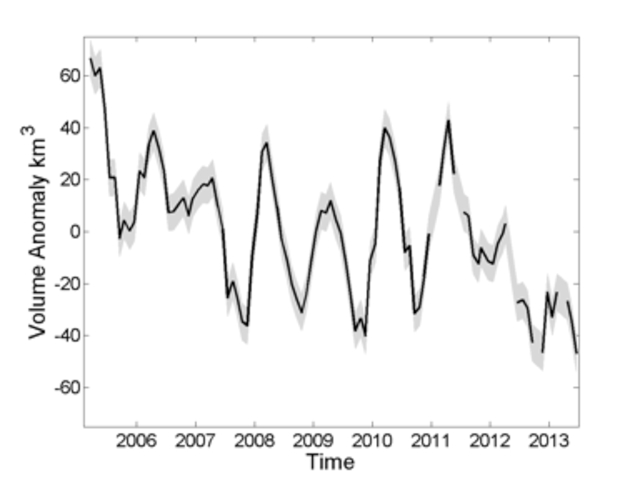

Stephanie Castle, a graduate student who works with Famiglietti, presented UCI’s most recent findings on Wednesday, December 11, in San Francisco at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union, the world’s largest Earth sciences conference. Like earlier studies of California’s Central Valley and the Tigris-Euphrates Basin in the Middle East, the UCI research team assessed fluctuations in water storage using data from NASA’s GRACE mission, a pair of satellites that translate changes in gravity into changes in water volume.

Basin Losses

From March 2005 to June 2013, the Colorado River Basin lost 5.7 cubic kilometers (4.6 million acre-feet) of water per year, or more than 47 cubic kilometers (38 million acre-feet) over the 100-month study period. The cumulative losses are equal to 1.3 times the storage capacity of Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir. Most of the water losses are attributed to groundwater pumping, mainly for irrigated agriculture.

The GRACE satellites measure total water storage – the water in mountain snowpack, reservoirs and rivers, soils, and aquifers. By subtracting the known quantities from other data sets, the value for each component can be reckoned. The research team is still analyzing those data, but preliminary results strongly suggest that groundwater is the prime culprit for the losses.

Castle told Circle of Blue that she compared the GRACE data to groundwater monitoring wells that are operated by state and federal agencies in the Upper and Lower Colorado River Basins. The water levels in the monitoring wells were consistent with what the satellites were detecting.

Though Castle acknowledged that water agencies in Arizona and Nevada – which, along with California, make up the three Lower Basin states – are storing water underground in a process called “water banking,” those savings accounts are relatively small when compared with the broader picture of water use in the region.

“There is some good local recharge in Arizona’s Active Management Areas,” Castle said. “But they are a small portion of the state.”

Cause For Concern

A sustained dry period, dating to 2000, has left the Lower Basin in a precarious position. In August, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation announced that next year it will cut the amount of water that is released from Lake Powell — this will be the first time this has happened under an operating agreement that was signed in 2007.

If the federal government’s river-flow forecast holds true, the lower release from Powell will set up the Lower Basin for a shortage that could be declared as early as 2015 or 2016. Such a declaration is based on how much water is in Lake Mead. Arizona and Nevada would be the only states to endure water restrictions at this first shortage tier. Moreover, water managers in Arizona told Circle of Blue in August that they would weather cuts in water deliveries from the river by pumping more groundwater.

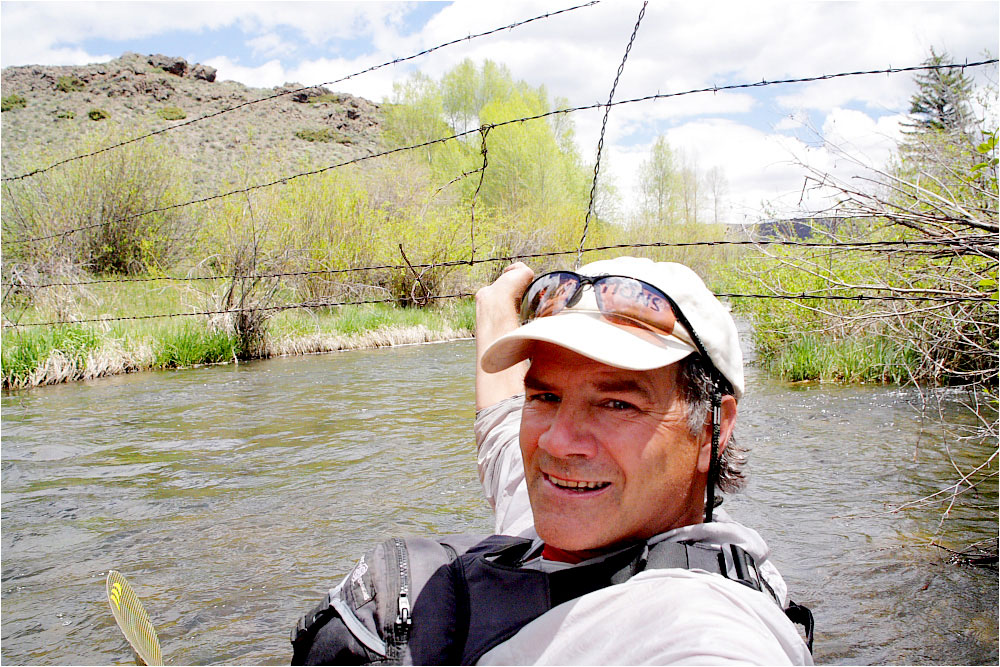

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Fascinating. Thanks for the article.

It is indeed a fascinating investigation and article. I would like to read the technical report to get an idea of the sensitivity (areal and vertical) of the measurements with the Grace data, and the potential error in the observed water levels vs. those obtained from the satellite data.