New Evidence Shows Fracking Contaminates Groundwater in Pennsylvania

A Duke University study finds methane in drinking water wells, along with two additional gases associated only with shale gas extraction.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

In the United States’s new natural gas game, distance matters to the bottom line – distance to water supplies, to waste disposal sites, and to hungry foreign markets. Distance also plays a role in water contamination caused by hydraulic fracturing, the production technique that is splitting open shale rock to release trapped gas and powering the energy boom.

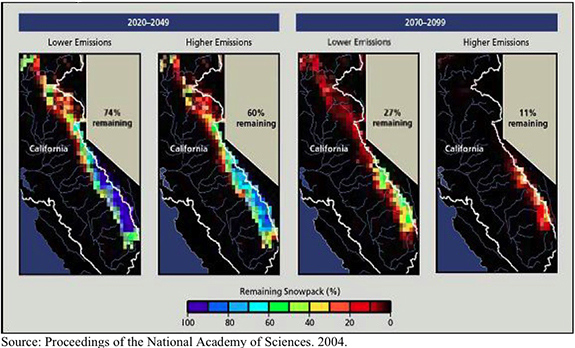

Drinking water wells within one kilometer of shale-gas drilling sites in northeastern Pennsylvania had methane levels six times higher on average than wells farther away, according to a study published online Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Methane was found in 82 percent of samples.

The authors suggest that poorly constructed gas wells are the most likely source of contamination, an assumption that will be addressed more rigorously in a future paper.

Led by researchers at Duke University, the study is consistent with the results of two other Duke studies that found methane contamination in water wells in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus shale formation and a hydrological connection between deep and shallow aquifers. None of the three studies has found groundwater contamination from the chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing, also called fracking.

The new study, however, tested water supplies for more than just methane and found a stronger correlation with fracking.

–Avner Vengosh, professor

Duke University

Researchers measured concentrations of two other gases associated with natural gas extraction, ethane and propane. Ethane was found in 30 percent of the water samples, and concentrations were 23 times higher for samples taken within one kilometer of drilling sites. Propane was found less often, in just 10 samples, all within one kilometer of a gas well.

Finding both ethane and propane in the samples is evidence that drilling operations rather than natural seeps, as industry boosters like to claim, are contaminating groundwater, said Avner Vengosh, a study co-author.

“You don’t find those components outside of the Marcellus formation and there is no biological source,” Vengosh, a professor of geochemistry and water quality at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment, told Circle of Blue.

Looking for the Source

The researchers took water samples from 141 wells drilled to a depth of 60 meters to 90 meters, 59 of which were within one kilometer of a drilling site. The Marcellus formation lies much deeper, between 1,500 meters and 2,500 meters below ground.

Drilling for shale gas in the Marcellus took off in 2009 when the number of wells quadrupled compared to the previous year.

To track the source of the gases, Vengosh and his colleagues analyzed elemental variations called isotopes, which provide a birth mark of sorts for the gas. Shallow natural gas is quite common in Pennsylvania and has a different isotopic pattern from the deeper sources in the Marcellus.

“The isotope work is quite helpful and can be used to fingerprint the source,” said Tom Richard, director of Pennsylvania State University’s Institute for Energy and the Environment.

Still, Richard told Circle of Blue, the results show a correlation between fracking and groundwater contamination – a strong correlation – but not causation.

In many cases baseline data to allow for before-and-after comparisons do not exist. In addition, a 2012 study from Penn State researchers found little correlation between methane concentrations and distance from gas wells, but the authors acknowledged that more research was needed.

The Duke study also raises as many questions as it answers. If faulty gas wells are to blame, which part of the well has failed? Is it the steel casings within the well, or the cement seals between segments of pipe? If the former fails, chemicals used in the fracking process could eventually move up the well, along with salts and heavy metals. If it is the latter, only gas from intermediate depths would be expected.

Geography matters too. In a study published last month in the journal Applied Geochemistry, researchers from Duke and the U.S. Geological Survey found no groundwater contamination from fracking in Arkansas’s Fayetteville shale formation.

Vengosh said it is impossible to tell whether the lack of methane in groundwater samples Arkansas is due to better well construction or a geology that is less susceptible to subterranean movements of gas. In the Marcellus, at least, the network of fractures, both natural and manmade, may increase the risk from a bad gas well.

Regardless, Richard argued, better construction standards for gas wells should be a priority.

On the research side, now that the Duke team has looked at the sources of contamination, its next publication will focus on pathways.

“The next level,” Vengosh said, “is how the source arrived.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Even if we groundwater contamination as a result of hydraulic fracturing is 100% clause by faulty pipes or cement sealants, the fact remains that Pennsylvania simply doesn’t allocate enough resources to inspect the oil and gas wells and God knows the industry will pay for that either so homeowners living near the wells are the ones who will end up suffering.

In the Jackson et al Duke study, they only show a weak correlation between amount of methane contamination and how old the site is. If the process itself is the source of contamination, wouldn’t we expect a stronger correlation here? Do they have evidence to reject the alternative hypothesis that these wells had high methane contamination before drilling and fracking began? After all, aren’t sites chosen for how rich in natural gas they are? I didn’t see them reject this possibility, but would love to see it if they have it.

Also it’s good to recall that potential groundwater contamination is only one among many objections to fracking. The lucrative jobs it supposedly generates don’t accrue to locals — companies bring in their own outside employees who already have the requisite training. Other objections include the polarizing effect it has on small rural communities (I have seen firsthand that it ruins friendships), and the impact to roads and calm communities that any large scale industrial operation has.