Satellite Data Shows U.S. Water ‘Hotspots’

Scientists who use the GRACE satellite say they need more resources to maximize its usefulness – for predicting floods and droughts.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

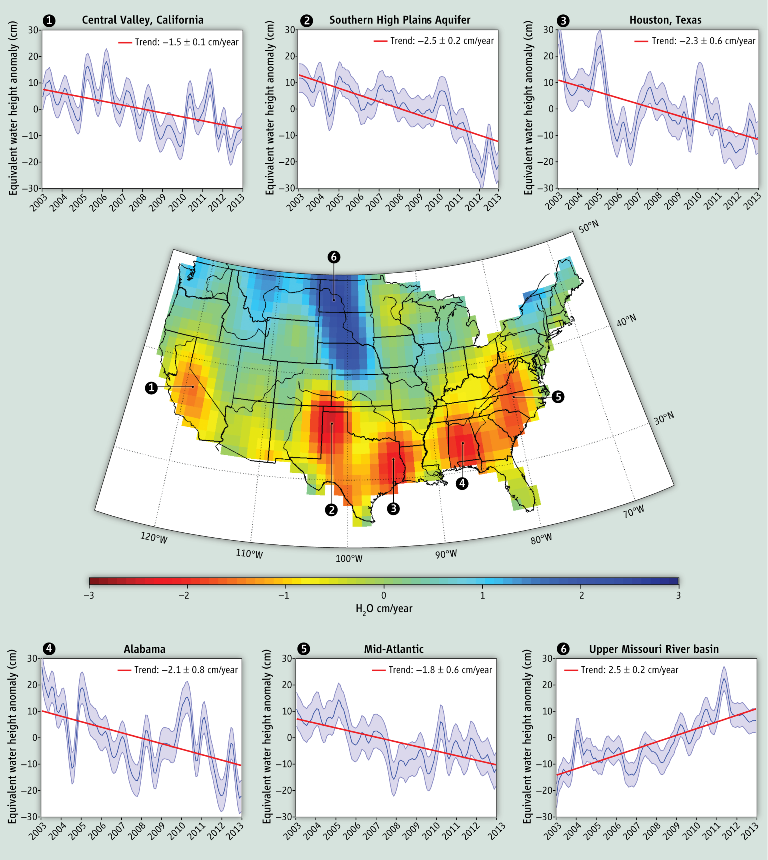

New data from a pair of satellites that have changed the practice of water measurement show significant fluctuations since 2003 in the water reserves of six areas of the United States.

These “hotspots” include some of the fastest growing regions of the U.S., some of its most important farmland, and some areas not typically considered water-scarce.

Water reserves declined in the metropolitan areas of East Texas and the farm-dense plains of the Texas Panhandle. Alabama, the mid-Atlantic states, and California’s Central Valley also showed notable drops in water storage.

“I don’t think there’s a realization in the Southeast that it’s this bad,” lead author Jay Famiglietti told Circle of Blue. Famiglietti is a professor at University of California, Irvine and director of the University of California Center for Hydrologic Modeling.

The Upper Missouri River Basin, by contrast, swelled. The region has seen severe flooding in two of the last three years.

–Jay Famiglietti,

Director, University of California Center for Hydrologic Modeling

Though only 10 years of GRACE data are available, the pattern of a drier southern U.S. and a wetter northern tier reflects the rule of thumb for climate change: that dry regions will get drier and wet regions wetter.

“These results are fitting right into the climate change picture,” Famiglietti said.

Famiglietti and co-author Matthew Rodell, chief of the Hydrological Sciences Laboratory at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, included the hotspot map in an opinion piece to be published Friday, June 14 in Science. They argue that the U.S. government should consider a national water policy and should spend more money on the satellite program, in order to maximize its potential for flood and drought prediction.

“Money has to be made available,” Famiglietti said. “Ultimately it has to come from Congress. We need to devote more resources to getting this data out quickly so that we can use it for seasonal prediction.”

The GRACE satellites detect changes in the Earth’s gravity field caused by shifts in water storage. By extrapolating from other data sets, scientists can pinpoint changes in water volumes between snowpack, lakes and rivers, soils, and aquifers for the entire globe. The satellites do not measure absolute volumes, just the relative change.

Right now GRACE data are available to researchers between two and six months after collection, Famiglietti said. The raw numbers need to be downloaded, corrected for errors, and processed.

Famiglietti estimated that tens of millions of dollars would be needed to accelerate the data-processing.

“It’s a manpower issue,” he said.

Coupled with short-term climate forecasts, quicker access to GRACE data could improve drought and flood prediction.

“GRACE tells you how full the bucket is,” Famiglietti said.

The twin satellites were launched in 2002. Since then they have provided hydrologists an eye in the sky to track monthly changes to water reserves around the globe. The satellites have revealed massive groundwater declines in the Middle East, in the breadbaskets of India and China, as well as in essential aquifer systems in the U.S., such as the Ogallala, which spreads across eight states in the Great Plains.

“What makes GRACE so important is its ability to sense changes in water below the land surface, including groundwater, which previously could only be measured by digging a well and monitoring the water level,” Rodell wrote in an email to Circle of Blue. “In most of the world, GRACE provides the only information we have on groundwater depletion.”

A new pair of satellites that can zoom in for a closer look, called GRACE Follow On, will be launched in 2017 to replace the current duo.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton