Scarcity in a Time of Surplus: Free Water and Energy Cause Food Waste and Power Shortage in India

Farm policies intended to remove risk from the grain-producing economy have pulled India from the perennial fear of famine. But inefficient bureaucracy and rampant corruption also promote the squandering of resources and a glut of food that is not reaching the poor.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

NAWANSHAHR, Punjab, India — Early on a sunny December afternoon, the road to Mandeep Sekhon’s eight-hectare (20-acre) farm swings past continuous fields of winter wheat, the first shoots of green peeking from the stubble of last summer’s rice. Just over a year ago, after a short career in business management, 32-year-old Sekhon inherited the farm, which has been in his family for four generations.

Though Sekhon is new to farming, his built-in support system includes Desraj Khai, the farm’s 57-year-old superintendent who has worked the family’s land for nearly five decades, since the time of the Green Revolution, when Western crop scientists introduced Punjabi farmers to hybrid seeds, chemical fertilizers, and chlorine-based weed and insect killers. Khai manages three growing seasons here in India’s northern Punjab state: two consecutive plantings of rice, in early spring and again in late summer, followed by a winter crop of wheat.

Sekhon watches as Khai uses a stout wooden rod to claw gaps in the walls of a narrow channel, directing a stream of water to the wheat paddies. Another stream of water pours into a concrete cistern near Sekhon’s house and barn, then drains without supervision into another set of paddies. Both streams come from the mouths of a set of irrigation wells that run 24 hours a day, whether the soil is dry or not. Both wells operate with electric pumps. And, as is the case with the millions of other rice and wheat farms throughout India, the state government provides the water and the electricity at no charge.

“It’s like anything else that’s free,” Sekhon remarks, as he gazes at the free-flowing water. “If you don’t have to pay for it, you don’t pay much attention to how much you use. Human nature, you know?”

Yet essential resources provided by the government to farmers for free are not nearly as liberating as India’s planners and senior government leaders once thought. India counts 129 million farms, according to the most recent farm census from 2005-2006. Those farms support 700 million residents, or more than half of all Indians and the largest voting constituency in the country.

Free water and electricity, like citizenship, are so widely considered a birthright that the pumps are never turned off. Rice and wheat fields generate immense and unmanageable grain surpluses. The country’s coal mining and electricity sectors — even as they steadily produce more fuel and more power — are still falling far short of the faster-rising demand. Blackouts and brownouts are endemic in India, dampening entrepreneurial development in both big and small manufacturing.

Heavily influenced by free water and electricity for farmers, India is in the grip of two trend lines, like heavy chains that are tightening around its national neck. India’s economy is slowing, even as its coal-fired pollution and climate-changing emissions are rising.

In sum, a confluence of popular and populist government policies, deeply rooted in the rural electorate — and guiding decisions on the Sekhon farm — are draining India’s natural resources, polluting its air and water, pressuring the treasury, and slowing the country’s development. Yet just as Americans decry the condition of the nation’s roads, but are not willing to raise taxes to pay for repairs, or Germans shut down nuclear power plants for safety reasons but turn to much dirtier coal-fired utilities to replace the generating capacity, India’s farmers are not anxious to change. They freely express their desire not to pay for water or electricity. India’s rural elected leaders, no surprise, do not ask them to.

Starvation To Surplus

Before the mid-1960s, when chemicals and modern seeds were not available, growers here produced an elegant feast of native fruits, grains, and vegetables. By the late 1970s, rice and wheat had supplanted native agriculture and grain harvests dominated farm productivity. In the 1980s, Punjab and neighboring Haryana state together became the largest rice and wheat producers in India. In 2011, the two states accounted for more than 23 percent of the nation’s rice and wheat crop, according to India’s Ministry of Agriculture.

Such productivity has invited intense scrutiny from outside India, as well as within. Agricultural economists and political leaders note, for instance, that not only did this region’s growers relieve the risk of starvation that gripped India throughout much of the 20th century, they also provided so much food that the nation’s population — now more than 1.2 billion — has more than doubled since 1970. But environmental scientists and public health specialists worry that the industrial farm practices have led India down a troubled and wasteful path to rampant water pollution and soil depletion.

India produces such immense crops that 62 million metric tons of rice, or the equivalent of 60 percent of last year’s 104 million metric ton harvest, is stored in government depots. Surplus rice is stacked in burlap sacks, like tiers of piled coal, bursting from dozens of government depots and private processing mills all across Punjab and Haryana.

Massive harvests are not periodic events here. They have become endemic — the result of mixing water, energy, politics, and policy into a potent formula of waste and inefficiency.

The broad outlines of India’s paradox are defined by the country’s insistence on removing as much risk from the grain-producing economy as possible. Along with free water and electricity, the government provides seed, fertilizer, and farm chemicals at little to no cost.

India also guarantees that it will purchase at generous prices and mill at no cost to producers every kernel of wheat and almost every grain of rice that is grown. Farmers receive 12.5 rupees for a kilogram ($US 0.10 per pound) of harvested rice. They are paid 13.5 rupees for a kilogram ($US 0.11 per pound) of harvested wheat.

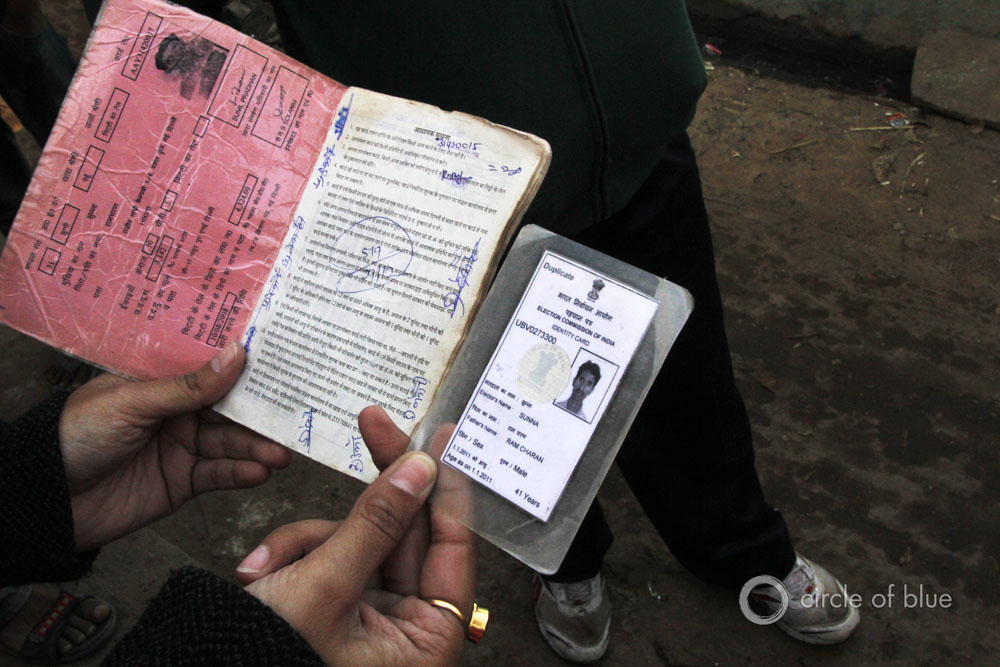

Moreover, much of what is produced is not reaching the hundreds of millions of poor Indians who need it, especially in the nation’s teeming cities. Though India provides rice and wheat at subsidized prices to its poor, those prices are still too high for tens of millions of families to afford. Additionally, India’s system for delivering rice to market is hampered by inefficient distribution and corruption. All of these barriers, in turn, reduce shipments of grain to market and add to the surpluses that are piled in Punjab and Haryana.

“The basic question is how long it can go on,” said Rajeev Bansal, executive engineer of the Haryana Irrigation Department. “It’s policy that is focused on helping the poorest. That makes sense. But it’s also not sustainable.”

Cycles of Risk

The question of sustainability is becoming ever more plain in the prime food-growing states of northern India, as well as in the coal-producing energy states to the southeast . Because so much of India’s grain is irrigated with groundwater that requires millions of electricity-consuming pumps, it is widely known that food abundance is depleting groundwater reserves, evidence of which can be monitored and charted from space.

But the pumps — more than 20 million operating nationwide — are not only draining aquifers, as has been extensively reported in recent years. Such mammoth pumping was the most significant reason that the farm sector sucked up 17 percent of the 772.6 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity that India consumed from its utilities in 2011, the latest year for the national figures, which is putting increasingly urgent pressure on India’s electrical generating sector, 65 percent of which is attributed to the coal mining industry. By contrast, there were only 3,000 pump-irrigation wells in 1960, prior to the Green Revolution, according to India’s Ministry of Statistics.

Neither coal production nor electrical generation, though, is keeping pace with the nation’s overall demand for electricity, which is rising nearly 7 percent annually, according to the International Energy Agency. India is adding roughly 20,000 megawatts of new generating capacity annually, and — though the country has started aggressive programs to build nuclear power plants and to develop renewables like wind and hydropower over the next two decades — 70 percent of India’s generating capacity will still be fueled by coal in 2030.

Such heavy reliance on coal to fuel India’s growing economy has turned India into the third-largest producer of climate-changing emissions, generating more than 2 billion metric tons of carbon annually, according to figures from the United Nations. By itself, India produces almost 7 percent of the world’s climate-changing gases, and its share is rising. The warming climate is producing erratic rain and snowfall in India’s grain-producing states, a problem which is reducing moisture and water that is available to recharge vital aquifers. As a result, farmers here in Punjab are drilling deeper wells and adding more powerful pumps to reach new depths, a practice that consumes even more electricity and produces even more climate-changing gases.

Groundwater Pumping and Food Production

Mandeep Sekhon and his family are well aware of Punjab’s falling water table. Four years ago, they spent more than 600,000 rupees ($US 11,000) to replace their two existing 50-meter (165-foot) wells with 100-meter (330-foot) wells, driven by more powerful pumps.

Since the mid-1960s, the farmers of Punjab have installed more than 1.2 million wells — about 87 percent of them electric and the remainder diesel — to irrigate their fields. And the number of new wells in the past decade has increased an average of 20,000 per year in Punjab, say state water authorities. Even in Haryana, where snowmelt is collected in reservoirs and 42 percent of irrigation water flows to farms through an extensive network of canals, farmers still rely on groundwater from more than 600,000 wells.

In the two states, the consequences for groundwater levels are dramatic. Decades ago, according to farmers and state government agriculture authorities, groundwater was reachable within 10 meters (about 30 feet) from the surface. But by June 1989, less than 15 percent of the groundwater beneath Punjab’s farmland was reachable within 10 meters. By June 2008, 61 percent was deeper than 10 meters, and the water table had sunk to more than 60 meters (200 feet) in much of the region.

In the years since, water tables in Punjab have fallen an average of 0.4 meters annually (15.7 inches) and as much as a meter (39.4 inches) a year in some regions of the state. An analysis last year by Columbia Water Center at Columbia University found that 90 percent of Punjab’s farms have deepened their wells at least once over the last decade and 20 percent have dug deeper wells at least three times.

Falling water tables are just as dire in other big farming states: the groundwater tables in Gujurat and Rajasthan, as well as parts of Andhra Pradesh and western Madhya Pradesh, have fallen below 300 meters (almost 1,000 feet). Climate change, according to state meteorological assessments, has made drought a yearly phenomenon. One-quarter of Rajasthan’s wells run dry every year. In the entire Indus River Basin — which includes Punjab and Haryana, as well as parts of Pakistan — groundwater pumping is estimated to exceed recharge rates by 50 percent.

Groundwater Pumping and Electricity

If there is a single prominent symbol for India’s resource-draining, energy-wasting, treasury-tilting farm policies, it is the electric water pump.

During planting and cultivating seasons, as much as half of the electricity in Punjab is consumed by electric irrigation pumps, according to the state’s utility. In Haryana, 37 percent of all electricity is consumed in pumping water from the ground or from one surface canal to another for agriculture, according to J.K. Juneja, the chief of engineering and planning for Haryana Vidyut Prasaran Nigam Limited (HVPNL ). In northern Gujurat, according to a study by the Columbia Water Center, half of the state’s electricity is used to operate water pumps for irrigation.

J.K. Juneja is at the top of the chain of command at HVPNL, the privately held builder and operator of Haryana’s transmission grid that is responsible for supplying the state with electricity. During an interview in his home in Chandigarh, the shared capital of both Punjab and Haryana, Juneja described how government policy that encourages waste in the use of water and energy damages the ambitions of needed private investment. Since 2007, said Juneja, Haryana has spent more than $US 7 billion to add 5,000 megawatts of new electrical generating capacity — more than tripling the electric capacity to 7,000 megawatts, much of it now fueled by coal. But that is still not nearly enough, because water tables are falling, farmers are installing more powerful pumps that suck up even more electricity, and blackouts and power-supply interruptions are damaging the state’s ability to attract new business and industry.

To keep up with demand, Haryana will add 10,000 additional megawatts of generating capacity by 2017, said Juneja. When asked if Haryana will have the financial means to build the equivalent of 10 new power plants over the next five years, Juneja raised his arms, palms up, and said, “I don’t know. But we need electricity. Other states have the same problem.”

And what is that problem? Actually, there are two: uncollected fees and uncertain fuel supplies.

Electricity Shortages and Diesel Substitutes

Because farmers do not pay for the electricity to pump water from the ground or from one river to another, the revenue of state utilities in Haryana, Punjab, and every other Indian state are perennially in deficit, relying on the national government for financial assistance.

Furthermore, the expansion and modernization of India’s national transmission grid is slow and uneven, say state power executives. Currently, India’s transmission grid wastes 25 percent of the energy it transports. In contrast, China’s transmission grid loses just 5 percent of the power it carries.

Not only are the funds funneling through the system inadequate, but the electricity itself is in such short supply that state utilities in this region and across much of the country set schedules for their customers. In Punjab, homes are supplied with electricity from late afternoon through the evening, as well as most mornings. Farmers, meanwhile, get power during the night and intermittently during the day. Power can — and often does — go out during an allotted time, however.

But there are ways to get around the electricity schedule, as well as any unscheduled electricity outages: intermittent power supply is so embedded in the Indian way of life that any farmer — or anybody else for that matter who can afford it — purchases and operates a diesel-fueled generator.

For instance, when the power goes off on Sekhon’s farm, diesel generators provide the electricity needed to run the irrigation pumps in the field. At his dinner table, the only subtle change is a slight dimming of the lights as the system seamlessly switches from state-provided electricity to at-home diesel generators.

The steadily growing number of generators reflects two market events:

- More people can afford them as middle class incomes rise.

- 40 percent of the $US 18 billion in annual energy subsidies that India provides for farmers, businesses, and drivers is devoted to reducing the price of diesel to well below market rates.

Petroleum consumption has climbed more than 40 percent since 2000 to 3.2 million barrels per day in 2012, 70 percent of which is imported, according to the International Energy Agency. More than 40 percent of India’s petroleum is consumed as diesel fuel, according to India’s Ministry of Energy. In September, after years of debate, India’s government began to phase out the subsidies for diesel, allowing state fuel sellers to raise the price a few percentage points each month until diesel prices reach the market rate, perhaps by 2015.

Policy Choke Point

When it comes to India’s water-food-energy nexus, the problem is not that water reserves are low. They are not. Rainfall is ample in much of the country. The glaciers of the Himalayan foothills and mountains of the north feed rain and snowmelt to more than a dozen major river systems. India’s annual renewable water reserves total 1,608 billion cubic meters (425 trillion gallons) a year, ranking it ninth in water supply among the world’s nations, according to the CIA World Factbook.

Likewise, the country also has ample land. India’s supply of arable farmland spans 183 million hectares (452 million acres) — second only to the United States — nearly 72 million hectares (178 million acres), or 40 percent, of which were planted with rice and wheat in 2010, according to India’s Ministry of Agriculture. For contrast, this was 31 million hectares (76 million acres) more than had been planted with rice and wheat in 1960, and the amount of this land that was irrigated went from 36 percent to 73 percent during the same period.

More water means larger crops. Tripling irrigation of rice and wheat led to a quadrupling of production, from 45.6 million metric tons in 1960 to 181.3 million metric tons in 2010. Yields increased from 1.9 metric tons of rice and wheat produced per hectare of land in 1960 to 5.2 metric tons per hectare in 2010.

Still, for a nation of 1.2 billion people that demographers predict will soon overtake China as the world’s most populous, India’s demand for grain is surprisingly modest. Most Indians do not eat soybean- and corn-consuming beef or pork. Last year, India’s farmers harvested 247 million metric tons of rice, wheat, and other food grains. Meanwhile, farmers in China, produced 571 million metric tons to feed the growing appetite for meat and dairy products of 1.3 billion people.

Yet — almost solely as a result of farm policy that ensures a glut of food — India threatens its water supply, wastes energy, drains its treasury, and adds to its growing fiscal deficit. The direct path to solving all of these circumstances is to adjust government policies to respect the market as much as it does the welfare of farmers. Big changes, though, are not likely to happen, say state government authorities in both the water and electricity sectors. In a democratic nation where so many people have come to rely on the state for help, the votes for such substantive change are few in rural India, if they exist at all.

Map by Jinah Park, undergraduate student at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism. Photos by J. Carl Ganter and Aubrey Ann Parker, Circle of Blue’s director and news editor, respectively. Reach them at circleofblue.org/contact, jcganter@circleofblue.org, and circleofblue.org/contact.

Choke Point: India is produced in collaboration with the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and its China Environment Forum, with support from Skoll Global Threats Fund. The Wilson Center’s Asia Program, which provided research and technical assistance, produces substantial work on natural resource issues in India, including articles and commentaries on energy, water, and the links between natural resource constraints and stability.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

According to IWMI, currently 80% of India’s irrigation is met by groundwater resources. According to NSSO, 2005, about 44% of farmers have electric pumpsets, and 66% have diesel pumpsets. Electricity is subsidized to farmers not just as a populist policy, but because of the huge transaction cost of collecting fee from farmers spread all over, and the fact that groundwater farmers bear at least 50% of the cost of water by investing on irrigation well/s, while surface water farmers are getting canal water virtually free of cost, as in many states, they seldom pay the nominal water rate. This is certainly a serious issue to discipline irrigation water use. While pricing electricity appears to be the quick economic solution, institutional economics clearly indicates the huge transaction cost of implementing this. Farmers have in some states removed electrical meters in protest. Estimates of electrical subsidy are not difficult to make, but in the absence of electrical meters, most estimates (are either over estimates or under estimates) lack realism. For example, if a typical 10 HP pump runs for one hour, it ought to consume 7.5 KWHs of energy. Usually in southern India, electricity is available for say 4 hours a day, thus 4X7.5 = 30 KWHs a day X 300 days = 9000 KWHs a year which @ Rs. 3 per KWH = Rs. 27000 per year. If we assume that the average HP per irrigation well of 10 HP, then each pumpset gets a subsidy of around Rs. 30,000 per year. However, this estimate lacks, information on crop pattern, extent of use of micro irrigation, vagaries of power supply etc. Thus, while electricity is crucial, groundwater is more crucial than electricity. Since farmers have apathy towards installation of electrical meters, they certainly are not averse to fix water meters. The Government /World Bank instead can think of fixing cheap and effective water meters on electrical pumps which will educate the farmers regarding grounwater budgeting. India’s groundwater predicament has to be solved with such efforts, rather than with legal tools alone. Education, building awareness among farmers by each State Government’s agriculture and irrigation department through water and irrigation literacy will certainly help. No state for instance including Punjab and Haryana have taken seriously the groundwater recharge on the farm at micro level for instance, other than watershed efforts at the macro level. Hope this clarifies.

MG Chandrakanth, Dept of Agri Economics, Univ of Agri Sciences, Bangalore, India

Good write-up but no suggestions, what to do with arable land. What is an alternative of wheat & rice. Crop irrigation by deep well is no doubt likely to be disastrous.