This Is India — TII

A correspondent’s thoughts on food, wildlife, transport, and politics.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

SHILLONG, India — This beautiful and tidy hill station city in Meghalaya, in Northeast India, is steadily expanding along the ridge tops and steep slopes of the region’s Himalayan foothills. Among the reasons is that few cities in India, and few Indian states for that matter, are as picturesque, as uncrowded, or as clean.

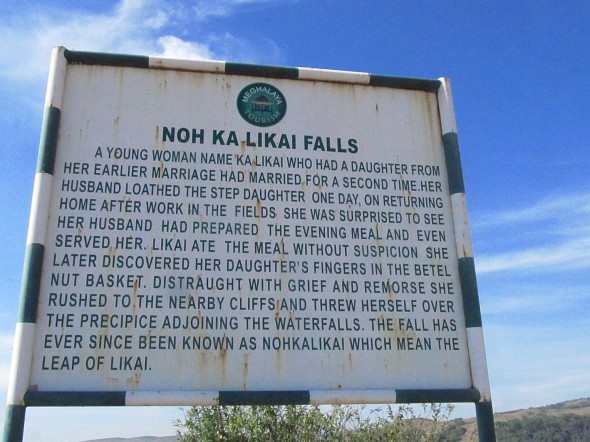

One striking example of Meghalaya’s natural beauty is Noh Ka Likai Falls, India’s tallest and most beautiful waterfall, which pours off a green and forested limestone cliff and plunges in a water-misted shower 330 meters (1,100 feet) onto a gold-colored outcropping of solid rock. White and bubbling, the stream ends its dive in a deep blue pool. Along the entire length of Noh Ka Likai Falls, from the daredevil jump into space, to the galloping turbulence of water rushing to fill the blue bowl, the whole of Earth seems to quiver with beauty that is unsurpassed by anything other than what is found in nature.

Yet this wonder of the world commemorates not the stream that links the sky and the land, not the ribbons of white and splashes of blue. No, this magnificent waterfall is said by Indian folklore and ritual to explore the import of the very darkest impulses of man. The legend that greets visitors on a big metal sign, and explains where the fall’s name originates, encompasses betrayal, jealousy, infanticide, cannibalism, and suicide. I kid you not.

The story is this. A young single mother newly married to a man jealous of his infant stepdaughter tricks his new bride into eating a meal made from the flesh of the baby girl. The mother discovers her daughter’s finger in the meal. Engulfed by disgust and horror she hurls herself to her death at the place where the water plummets from the cliff.

I explained to my Indian guide that in the United States and other western nations such a magnificent display of nature’s elegance would typically be honored with a name that marks its location, its discoverer, or what it inspires in the human spirit. Ruby Falls in Tennessee. Grand Falls in Arizona. Cumberland Falls in Kentucky. Bridal Veil Fall in California.

Meghalaya is different. Here a great waterfall recounts a monstrous tale of infanticide, cannibalism, and suicide.

TII. This is India.

Generally, toward the end of my travels and frontline reporting in nations outside the U.S., I collect the various and intriguing threads — events or locations or people — that strike me as emblematic of a western journalist’s experience in a different place. They come together in essays that I call TII — This is India. TIM — This is Mongolia. TIC — This is China. TIQ — This is Qatar. The titles are borrowed from a scene in Blood Diamond, Leonardo DiCaprio’s great 2006 movie about diamond mining during the civil war in Sierra Leone. Asked, while having a drink in an African watering hole, about a peculiarly confusing trail of events that made no sense, DiCaprio tells his mate: “TIA. This is Africa.”

In that same spirit, here are other points of interest from my latest trip to India.

Driving habits that are apparently reckless, but not really — I’ve encountered interesting taxi and hired-car rides on my journeys around the world. None are as initially hair-raising as they are in India. A year ago, in Punjab, the apparent two-lane highway was most often treated as an unofficial four-lane road. Cars, trucks, and buses, side by side heading east, side by side heading west, careening toward each other, weaving in and out of their lanes, horns blasting. Along the shoulders cows and dogs and goats and kids and adults and bicyclists and oxcarts and horse-drawn wagons trudged in both directions.

To leave the traffic lanes for any reason was to invite serious injuries, or deaths, of animals and people. Not to get out of the way of onrushing vehicles coming your way while traveling in the traffic lanes was to invite your own serious injury or death. After a time you just get forced to become accustomed to the pandemonium, or you exist as an emotional wreck.

So it was in mid-January, when I returned for my third trip to India, and realized I’d grown accustomed. I jumped into a cab at Delhi International and swung off into evening rush hour traffic. The driver weaved across lanes, bolted by slower traffic, squeezed through impossibly small openings between diesel buses and bigger diesel trucks. He sped with reckless velocity, all to reach my hotel some five kilometers distance.

At the end, the last half-kilometer, the driver turned left onto a choked boulevard and headed east against three lanes of oncoming traffic. Doing so meant avoiding a two-kilometer roundabout and service road, and more traffic. We even made our way through a 200-person wedding party on foot that was all aflutter with the sounds of drums and trumpets and cymbals and flourescent spotlights. Nobody, not any person in the wedding party, nor any of the oncoming drivers, cared. Not a horn sounded. Not a word of protest was uttered. I arrived at the hotel entrance heading in the wrong direction. I thanked my driver. Tipped him well for his skill. Marveled at my own comfort and ease. And thought — TII. This is India.

Eating and drinking in different places in the same hotel — In Guwahati, a big city in Northeast India and the capital of Assam, I encountered unusual strictures involving food and beer. The hotel where I stayed, in the company of Dhruv Malhotra, a talented Indian photographer, had a fine vegetarian restaurant on the first floor, and a small bar on the second. We ordered dinner and asked for the beer and wine menu. No, we were told. No alcohol is served in the restaurant, only in the bar. But typically the bar doesn’t serve major meals, only snack foods. What to do? We ordered from the restaurant and then went upstairs to the bar. Explaining the situation, we asked whether we could eat our fine vegetarian meal in the bar. No problem, we were told. Dinner will be served straight away. TII. This is India.

India’s Internet is terrible — I hate paying for Internet service as an extra in western hotels. I see it as an affront, a gouging. I almost never stay in hotels in the US or Europe that charge extra for Internet.

I’m not nearly as unwilling in India. As a journalist wedded to the information gathering, communication-enhancing power of the Internet, encountering lousy service or no Web connection at all makes me jittery, like drinking too much coffee at night. India has terrible Internet connections. I still look for free Web privileges in Indian hotels, but I’ll pay handsomely for good Web connections, which are rare. That’s why I can recommend without hesitation the Highwinds Guest House in Shillong, which is reasonably priced, and has comfortable rooms, terrific service, good food, and a very strong, reliable, and free Internet connection. Surf’s up.

India is mesmerized by its mega fauna, its top-of-the-food pyramid wild species — After three trips to India, three trips that take a veteran environmental journalist through the heart of a big nation’s water supply, energy production, and food harvesting infrastructure, it’s not hard to make the case that there’s scarce oversight of India’s natural resources. Except one category. The country’s big beautiful wild cats, elephants, surviving Indian rhinoceroses, and other beasts of the forest.

Four white Indian lionesses were killed in January crossing a rail line in central India, an event that was widely reported. The coverage bore the ribbons of mourning and condolence.

Meghalaya’s wild elephant herd, which the Ministry of Environment and Forests now numbers at over 1,800 animals, is growing so fast that splinter herds, made up of independent males and young adult females, regularly crash through villages and tear up fields. It’s illegal to kill an elephant in India. State authorities aren’t shy about prosecuting violators, no matter the motive. So elephants have taken charge of the forests and valleys, a trend celebrated by the state news media.

Elephants, in fact, are beloved in India. There’s really no comparable equivalent of wild animal love in the U.S. A group of men was arrested in Assam last month, for instance, and prosecuted for animal cruelty after their truck carrying a female elephant was stopped and inspected. The elephant was in chains and apparently deprived of food and water.

People who protect wildlife are seen as national heros in India. A young man from Rajasthan was held up as a martyr in late January after he and a group of villages attacked two poachers in a game reserve who were hunting chinkara, Asia’s smallest antelope species. The 25-year-old villager was shot by a poacher wielding a double-barreled rifle.

One species, the Indian tiger, seems to be holding its own with a lot of public support. A tigress roaming in Punjab, in northwest India, has stalked and killed nine people, using the region’s thick sugarcane fields for cover. Another tiger in Uttar Pradesh, a mountainous northern state, has killed 10 people since the end of December. The Indian press seems clearly to be on the side of the tigers, whose appetite for man-flesh appears prodigious. Ten kills in six weeks?

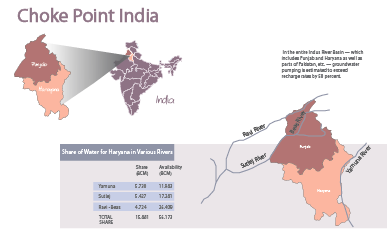

And as we noted last year in Circle of Blue’s Choke Point: India project, titled Leopard in the Well, that graceful, powerful, and lethal big cat is a constant source of Indian news. A Dharmpuri village farmer in Tamil Nadu, a southern Indian state, sent his neighbors into a panic this month when a leopard wandered out of the brush to attack, kill, and drag away a goat tied to a stake outside the man’s thatched home. “I heard the bleating,” he told a reporter. “I saw the leopard dragging my goat away.” Imagine. A hungry leopard taking advantage of an easy meal. TII. This is India.

Breakfast is unapproachable. But other Indian meals are great — I don’t think there’s any argument that breakfast in the developed West can be excellent, and entirely approachable. Choose among the following: eggs, toast, home fries, pancakes, biscuits, bacon, sausage, cheese, fruit, pastries, coffee, tea, milk, fresh squeezed juice, butter, jams and jellies. It’s all inviting, colorful, healthy, delicious and, above all, recognizable.

Breakfast in India bears none of those traits. I’ve spent almost nine weeks in India on three trips that spanned four regions and eight states. I’ve stayed in more than a dozen decent hotels and guest houses, and awakened to more than 60 daybreaks. In all those days, at all those places, I recognized what I’ve eaten for breakfast in two places.

At 11 Delhi, Ajay Anandd’s wonderful and comfortable guest house in New Delhi, a delicious breakfast of eggs, toast, fruit, yogurt, granola, juice, tea and coffee is served each morning.

The second time was in a guest house high on a Himalayan ridge in Uttarakhand, along the Mandakini River, when I was essentially served lunch for breakfast — a medley of spiced dals, nan bread, and strong coffee.

Indian breakfasts typically consist of a featureless gruel, some sort of stale bread parts, maybe a partially boiled egg. Other Indian meals are fabulous; gorgeously spiced chicken or beef or vegetarian, pulses and dals, garlic nan bread, and very good beer. Breakfast? Forget about it. In Shillong I usually ordered strong coffee, opened the day with a packaged chocolate bar, and waited until it was time for lunch.

Bandh! Shutdown City — After a day of witnessing the depradations of land and water caused by careless coal mining in the Jiantia Hills east of Shillong, we had to race out of the region to beat the roadblocks planned by insurgency groups that have been warring with the Meghalaya state government for decades. In Meghalaya and other Northeast India states, the insurgents regularly flex their influence muscle by declaring a “bandh,” a shutdown.

The goals of the anti-government insurgents are disruption, bullying, intimidation, and amassing of influence and power. They’ve succeeded in prompting a big and expensive police presence in Shillong, the capital, and causing ordinary citizens to comply with the episodic road closings, traffic stops, store closings and the like. The insurgents regularly shake down truck drivers for bribes and have apparently built a sufficient economic infrastructure to employ an unknown number of people. But they clearly have done nothing to improve the well-being of ordinary citizens or advanced public goals, like pollution prevention. Most people I met here describe the whole insurgency charade as a nuisance that at times can be dangerous. The killing of prominent citizens and government officials occurs periodically.

The road blocks in the Jiantia Hills was my second encounter with a bandh in Meghalaya. The first bandh was called on January 26, Republic Day, when shops and roads were empty, city and village life receded, and curtains were closed across seven states of Northeast India. This shutting of the countryside occurred on a national holiday that commemorates the signing of the Indian Constitution. Residents honored the bandh, a display of bullying, because they are intimidated by groups that have varying goals — most of them directed to government breakdown — and are armed with weapons superior to those carried by the police.

As I noted on a Facebook post, three Americans were randomly killed in a Maryland shopping mall that same weekend. Reuters reported on the ongoing escalation of gun-related violence in the U.S. and noted that since December 2012, when all those first graders were murdered in Connecticut, there have been 36 school shootings in our country. 36.

One cause is our national helplessness to respond in any way to the political insurgency, the American bandh, that intimidates voters and prevents any reasoned change in oversight that could protect our children. I think of the bandh in October, the shutdown of the American government not for a day, but for three weeks. I think of the frustration, the havoc, the needless fear that such intimidation fosters. I think that while Americans still believe that we are so special, the death toll from our insurgency, our bandh, our distinctive forces of intimidation, is much higher in the United States than it is India.

As I noted to a young Indian student sitting alongside me on the plane from Guwahati to Delhi, the Meghalaya insurgents are doing nothing to prevent the damage to land and water from the region’s coal and sand mines, which cause rivers to turn blue and red and yellow. “Oh yes,” she said. “But in America rivers run red….with blood.” TII. This is India.

–Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!