Californians Will Vote on Big Water Bond Not Knowing Exactly What They Are Buying

Rules for choosing the most controversial projects will be written later.

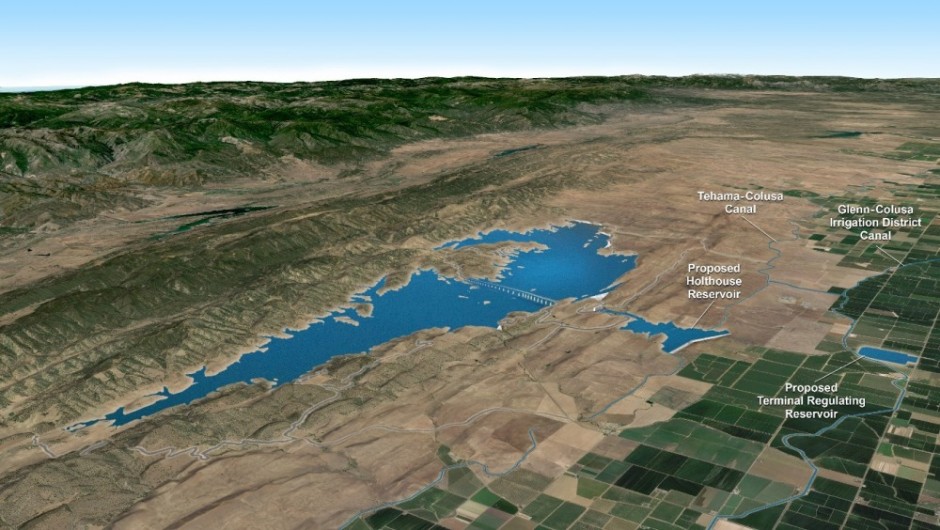

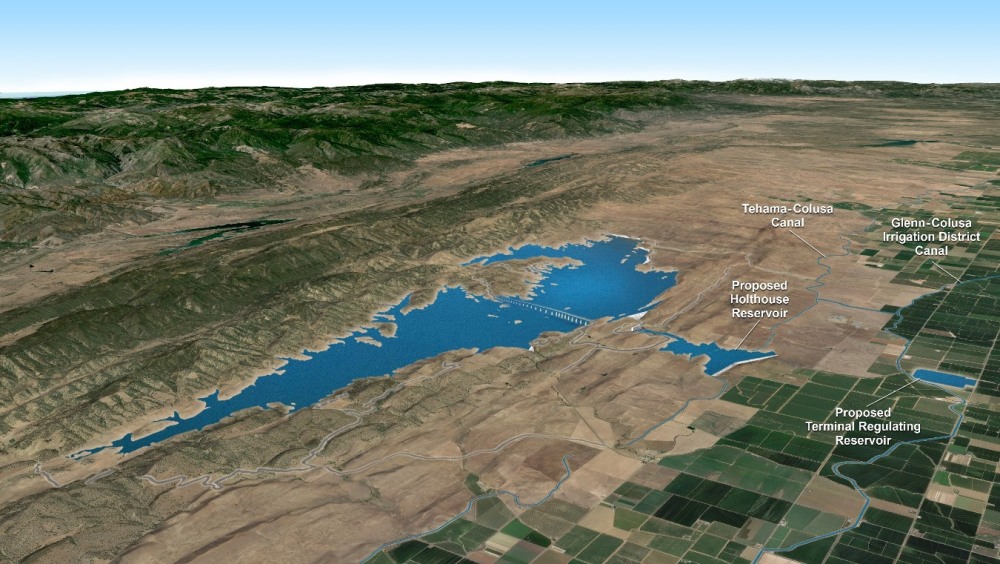

Sites Reservoir in northern California is one water-storage project that could be funded by a $US 7.5 billion water bond that California voters are being asked to approve on November 4. Photo © California Department of Water Resources

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

When Californians close the musty drapes of the voting booth on Tuesday, they will face a $US 7.5 billion question: Should the perpetually water-worried state, in the midst of a record drought, use its taxing authority to pay for another set of state-funded water projects?

If the voters say yes – as the polls suggest is likely – Proposition 1 will be the seventh and most expensive water-related bond passed in California since 2000. The bond will finance a host of initiatives, from projects to clean up polluted aquifers and revive wetlands, to investments in rebuilding dilapidated levees.

But voters will mark their ballot without knowing how the most controversial slice of the funds – money dedicated to storing more water – will be spent.

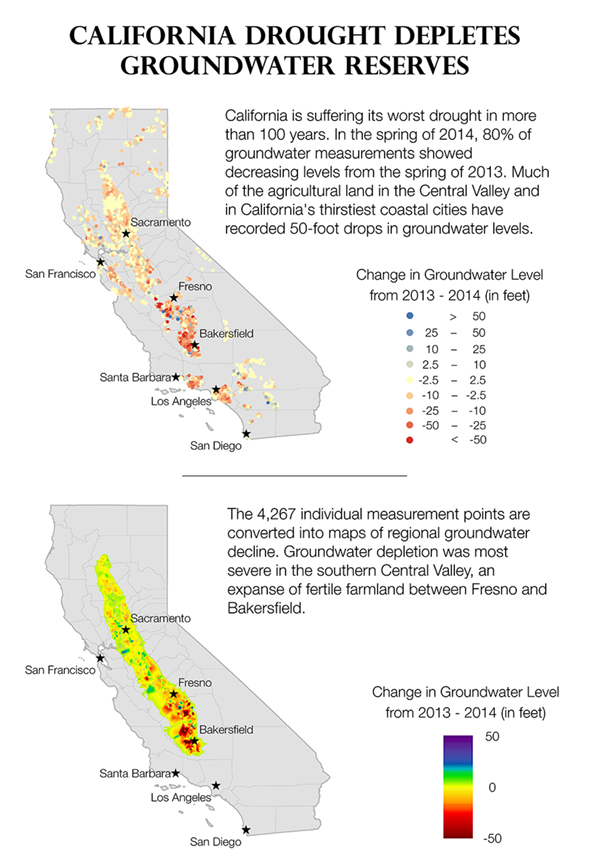

The rules for evaluating, comparing, and selecting competing water-storage proposals have not yet been written, according to Susan Sims, the executive officer of the California Water Commission, the nine-member body that will decide how to spend the $US 2.7 billion apportioned to water storage. The money could be used for new dams, for operational changes at existing reservoirs, or for refilling depleted underground aquifers.

The bond does not earmark dollars for specific storage projects, but more than one-third of the funds are directed toward that general purpose.

Assuming the bond passes, the California Water Commission will have to set the ground rules for how it will make important decisions for allocating a significant amount of taxpayer money.

“Over the next two years, the commission will look at existing scientific and economic work,” Sims told Circle of Blue, noting that funds for storage cannot be handed out until December 2016. “A lot of big issues remain to be dealt with.”

Creating a Scorecard

Though the bond funds will not help the state’s 38 million residents cope with the current moisture crisis, supporters of Proposition 1 are promoting the measure as a down payment that will prepare the nation’s most populous state for a future that will bring both crippling drought and engulfing floods.

Those preparations cover many areas. The bond, which passed the state Legislature in August with near unanimous support, allocates money to four broad categories of project, from watershed restoration and flood protection to facilities that cleanse polluted drinking water.

By far the most debated piece of the bond is the section on water storage, which was boosted by $US 700 million dollars in negotiations this summer to ensure legislative approval by appeasing Republican lawmakers from Central Valley farm districts.

The people controlling the purse strings for storage funds are the nine members of the California Water Commission. Appointed by the governor, the commissioners will select which storage projects will earn state backing. The commission has a lot to consider.

First, are the types of projects eligible for funding. Four dam projects connected to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the state’s most important waterway, are included, as are projects that add water to the state’s ever-shrinking groundwater reserves. Bond funds will cover half of a project’s costs.

Next are the “public benefits.” Any storage project must contribute to the common good. The bond lists five types of public benefits that the California Water Commission must assess: ecosystem improvements, recreational benefits, capacity to respond to drought, improvements in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta’s water quality, and flood protection.

But the list does not say how to compare and evaluate these criteria.

“In the end, it is the weighting of these public benefits that will have a major impact on the types of projects that will be funded,” notes an analysis of the bond by the Pacific Institute, a public policy think-tank.

What is the value of a new dam versus letting more water soak into exhausted aquifers? How does expanding an existing dam in northern California compare to adding groundwater storage capacity in the southern San Joaquin Valley? How large a public benefit is more jet-skiing territory?

The California Water Commission does not have answers to these questions yet, and the members are just now beginning their assessment. The commission has heard presentations from the California Department of Water Resources about the economic models it uses, as well from the Bureau of Reclamation about the process for federal water storage projects.

“What lies before the commission is first, how to evaluate public benefits and second, how to get input from the people doing these projects,” Sims, the executive officer, said. “The challenge is the methods you use to quantify, measure, and compare projects.”

Some criticize this approach as being too narrow. Jay Lund, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of California, Davis, reckons that projects considered for the $US 2.7 billion pot of money should be evaluated as a group, to test how they improve the state’s entire water system.

California has all sorts of computer models for assessing its water system, Lund told Circle of Blue – models for state and federal water deliveries, for groundwater fluctuations, for river flows, and for water pollution. But a unified tool for comprehensive observations has not been developed.

“This is a good opportunity to pull all these parts together,” he asserted. “They exist but they certainly are not coherent at this point. Ideally you’d look at a portfolio of storage projects and see how they work together.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Regarding “new dams versus letting more water soak into exhausted reservoirs”. I don’t think it is a “versus” question. Reservoirs are filled by RUNOFF when the ground cannot soak up any more water at that time. Several days of heavy rain produces a lot of runoff and sometimes flooding. That water should be saved in reservoirs. It could even be put back into aquifers through “dry wells”.