In Record Drought, California Scrambles for Answers

President Obama urges cooperation. But Republican opposition and a maze of state plans are causing a frantic confusion, while vulnerable farmers see immediate and long-term pain.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

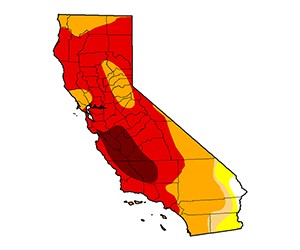

FRESNO, California – President Obama dipped a toe in California’s combative water politics Friday, as one of the worst droughts in the last half millennium has the nation’s largest economy and most populous state on the verge of a disastrous water crisis.

Obama’s visit to the Central Valley, one of the state’s hardest-hit regions, underscores the severity of a drought that threatens to permanently shrink agriculture in one of the nation’s most productive food baskets. Three years of dramatically below average precipitation have exposed a frightful truth for many of California’s 38 million residents: reservoirs that look like sandboxes, wells that spit out air instead of water, and the dawning realization that the state does not have enough water to meet all demands.

“Everyone is scrambling to get through this year,” David Zoldoske, director of the Center for Irrigation Technology at Fresno State University, told Circle of Blue. “If there is little rain, there will be carnage in 2015.”

Obama offered a temporary lifeline, pledging roughly $US 200 million in cash assistance for California ranchers, farmers, and food banks. The money is part of a $US 1.2 billion disaster relief package that the president announced yesterday along with a $US 1 billion climate change adaptation fund, an item in his 2015 budget proposal due in March. Disaster aid will also be made available to states in the Great Plains and Midwest that have experienced recent droughts and blizzards.

The president unveiled the two proposals while touring the Central Valley, a Massachusetts-sized belt of rich soil and limited water. Home to nearly 7 million people, the valley is the heart of California’s $US 44 billion agriculture economy. It is the state’s most vulnerable region to prolonged drought, and, as the president learned, it is the source of the state’s most bitter water debates.

After observing a roundtable discussion about local agriculture, Obama urged community and state leaders not to think of water as a game of winners and losers.

“We can’t think of this simply as a zero-sum game,” Obama said, speaking from a barren field on the west side of the valley, an hour from Fresno.

“It can’t just be a matter of there’s going to be less and less water so I’m going to grab more and more of a shrinking share of water,” Obama continued. “Instead what we have to do is all come together and figure out how we all are going to make sure that agricultural needs, urban needs, industrial needs, environmental and conservation concerns are all addressed.”

That is a tall order, requiring a radical reinvention both of California’s water supply hardware and its operation – changes that politicians, environmentalists, and farmers have fought over for decades. Indeed, the drought has catalyzed a consensus that something should be done, but there is little agreement about the details.

A New Water Future

Water experts broadly agree on the policy menu. To start, the state can no longer turn a blind eye to annual deficit spending of its groundwater accounts. Nor can it ignore the need to develop the next generation of water infrastructure. New ways to capture, store, clean, and reuse water so that the state is prepared for long-term changes in its climate are essential. Prices and markets, made easier thanks to the state’s extensive canal systems, will be necessary to discourage waste and increase productivity.

These options have been on the table for years, but California’s politicians have dithered. The drought has the capital in a frenzy, yet time is already running out this year. The deadline for filing bills in the legislature is in two weeks, and the governor’s office and the legislature have an overflowing agenda. Top priorities include emergency drought relief, an updated water bond, and giving teeth to the state’s groundwater regulations, not to mention the prospect of a controversial $US 25 billion pair of water-supply tunnels through the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, a fragile ecosystem.

“I don’t think [the governor’s office] can articulate what they want to see manifested in a new groundwater policy.”

–Dennis O’Connor, principal consultant

California Senate Committee on Natural Resources and Water

Leaders in the state assembly say they are focused on the money. A twice-delayed $US 11 billion bond is scheduled for the November ballot, but four competing versions have been introduced, ranging in cost from $US 5.8 billion to $US 9.2 billion.

“At this point, I am focusing all my attention on passing a water bond that voters will approve, so I appreciate the work of many others on the need to address the immediate drought issues facing California,” Assembly Member Anthony Rendon, chair of the Water, Parks, and Wildlife Committee, told Circle of Blue.

Groundwater policy is a drought issue with consequences now and well into the future. In years like this one, when farmers and water districts expect to receive no water from rivers, groundwater is the emergency source, and it is in high demand. Well drilling companies in the Central Valley told Circle of Blue that the backlog for a new well is between six months and a year.

The state is running annual groundwater deficits, and total water storage in the state is at an 11-year low, according to NASA satellite data. (11 years is the extent of the satellite data record.)

Legislative officials said that the governor’s office has taken the lead on groundwater and the governor wants to empower local agencies to manage aquifers.

Because the state has such variety in its aquifers and management agencies, local control is important, said Dennis O’Connor, the principal consultant to the Senate Committee on Natural Resources and Water and the Senate’s point man for groundwater policy. But the governor’s office is floundering on the details.

“I don’t think they know what they want to do,” O’Connor told Circle of Blue on Wednesday, having just come from a meeting with the governor’s staff. “I don’t think they can articulate what they want to see manifested in a new groundwater policy.”

The governor’s 2014-15 budget proposal does include $US 11.9 million for groundwater, money that will be used to hire enforcement staff, monitor aquifer levels, and assess pollution in aquifers used for drinking water.

The Orange Growers of Fresno County

For one example of how bad the drought is and the direction of the Central Valley’s future, consider the east side of Fresno County. This is citrus country. Thousands of acres of orange groves press against the Sierra Nevada foothills, which are brown and withered today and veiled by smog.

In a normal February, those hills would be green, says Loren Booth, owner of Booth Ranches, which oversees 40 orchards on 3,360 hectares (8,300 acres) in the Central Valley and runs a small livestock operation.

Booth already cut her cattle herd in half because the grazing pastures are dry. To the survivors she is feeding oranges that spoiled in a December deep freeze. Orange-fed beef is not the next food trend, she said, but the cows love it.

Farmers in this part of the county are in a difficult situation. They expect very little water from the Friant-Kern canal, their primary supply, and groundwater is scarce here. That leaves them with few options except for removing old trees to save moisture and hoping for rain. Booth has a feeling that a lot of her colleagues will lose the farm.

“I don’t think a lot of orange growers will make it through this year,” Booth told Circle of Blue, her voice breaking ever so slightly. “We’re in a crisis.”

Mike George who works at nearby Mulholland Citrus is feeling the same pressures. His farm, which also relies on the canal, might get enough water to keep trees alive, but not enough to grow a crop. Like Booth, he will rip out old trees to save water. How many? It is too early to say.

“We don’t have many options,” George told Circle of Blue. “We’re in survival mode.”

David Zoldoske, who has worked at Fresno State for 31 years, sees this as the future of agriculture in the Central Valley. Fewer acres will be irrigated. Less groundwater will be pumped. But those conversations about transition and the investments for a more sustainable tomorrow have to begin now, he argues.

“We want to farm this valley for hundreds of years,” he said. “The stupidest thing would be for my grandkids to look back at their grandfather’s generation and see that we didn’t do anything. That we destroyed this resource. At some point, we have to make a commitment to sustainability. Everyone has an interest in that.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!