India’s Treacherous Coal Mines in Meghalaya

National court orders end to feudal labor conditions, wanton water pollution, and deadly accidents.

By Keith Schneider, Circle of Blue

SHILLONG, India – In the coalfields of Meghalaya, a wild and rural state in Northeast India, income and social standing are, quite literally, correlated on a perpendicular scale.

Mine owners live in handsome homes on the high ground, above the monsoon mud and flooding. They earn such favorable returns extracting coal from the state’s deep and dangerous box mines they can afford to send their children to Ivy League universities in the United States.

The undocumented boys and men who descend 65 meters (213 feet) into the darkness of Meghalaya’s unregulated mines live on the mudflats and near the banks of Meghalaya’s polluted streams. The walls of their huts are made of tree branches. The roofs are constructed of plastic sheeting. They frequently have to walk long distances to secure clean drinking water.

Each morning miners risk their lives to earn $8 to $10 a day to crawl through three-foot-tall tunnels and claw at seams of coal with pick axes and steel bars.

Coal has been mined by hand this way since the mid-19th century in Meghalaya, a hilly and forested state of 3 million residents northeast of Kolkata, between Bangladesh and Myanmar. A few thousand tons were drawn each year from tunnels dug into the sides of hills and used for cooking, occasional heating, and for export to Assam and other neighboring states.

In the early 1970s, as the steel and chemical industries developed outside Guwahati, Assam’s capital, wealthier farming families began to dig deeper to mine seams of coal beneath their land. By the 1980s many more large and deep box mines, and innumerable long tunnels, known as rat holes, formed three distinct coal mining districts — the Jaintia Hills east of Shillong, and the Garo and Khasi Hills west and south of Meghalaya’s capital.

Meghalaya’s mines have never been licensed or subject to India’s laws restricting child labor, environmental discharges, or worker safety. Nobody knows how many rat hole or box mines exist. A census has never been conducted. In interviews mine owners say there are too many to count.

“Everybody in this area is connected to the mines in some way,” said Shibun Lyngdoh, a mine owner and ward commissioner in the East Jaintia Hills district. “All of us grew up with the mines. They are all across the land. This is what we do here.”

By the turn of the 21st century, Meghalaya’s coal production topped 5 million metric tons annually — one percent of India’s total coal production at the time, according to the state Department of Mining and Geology. Tens of thousands of immigrant miners, many of them from Bangladesh and Nepal, provide the hand labor. The narrow highways that serve the mines were long ago ground to dust and stones by heavy trucks that form impenetrable traffic jams.

Meghalaya’s mine regions, in effect, form a nearly perfect example of the consequences of either an unregulated free market, or what ecologist Garrett Hardin defined in a famous 1968 essay as the “tragedy of the commons.” By behaving in ways that serve only their self interest, mine owners and Meghalaya’s hands-off state government are depleting the coal resource, wrecking the land and water, and putting an immigrant labor force in harm’s way.

“You can’t really believe the extent of the damage unless you go there,” said Ritwick Dutta, an environmental attorney and founder of the Legal Initiative For Forest and Environment, a public interest law group based in New Delhi. “The land and the water are being systematically ruined.”

Coal Mining Claims Another Region

Like the incredible ecological ruin that is occurring in many of the world’s other fossil energy development regions — West Virginia’s mountaintop removal strip mines, the tar sands of Alberta, Canada, and Nigeria’s polluted coastal oil drilling region — coal mines are laying waste to Meghalaya. The damage is confirmed in over a dozen formal reports by universities, Central Government agencies, and the media.

Tens of thousands of acres of forest have been cleared for mines and for the staging areas where coal is stored in piles, sorted, and then loaded by hand onto trucks. Seasonal monsoons strip away trees and wash away the topsoil, producing a desert of sparse grass and shrubs.

The high-sulfur coal mixes with water to form an acidic solution that turns streams the color of dried blood. In 2007, the Lukha River startled fishermen by turning a deep, otherworldly acidic blue. At night, small coal fires needed to sharpen tools and for cooking are smoky cauldrons burning across the dark land.

The toll on people is equally distressing. Murder and rape are common and often uninvestigated, according to the regional and national media. Crippling injuries and deaths from falls, cave-ins and drownings are facts of mining life. On February 4, 2014, for instance, four miners were buried alive when the walls of a box mine in the Garo Hills collapsed. Eleven days later the bodies of three male miners and a woman were recovered from two abandoned box mines in the Jaintia Hills.

These recent accidents, and many more in previous years, describe the expansive social and economic distance that lays between mine owners and laborers. It is a geography of lawlessness, workplace risks, environmental waste, and governmental tolerance.

|

|

|

|

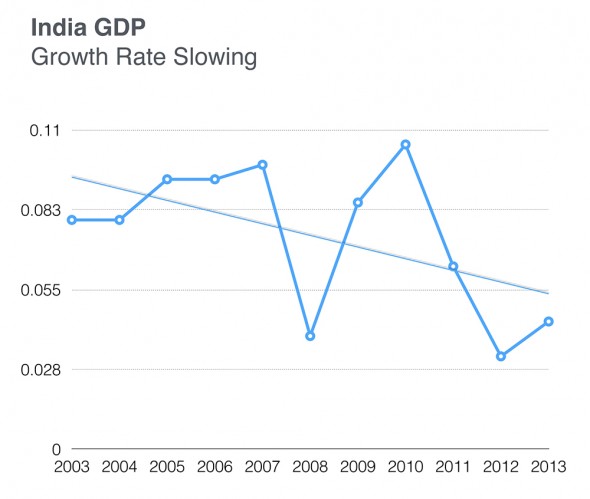

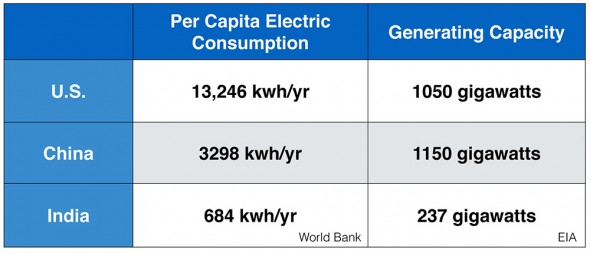

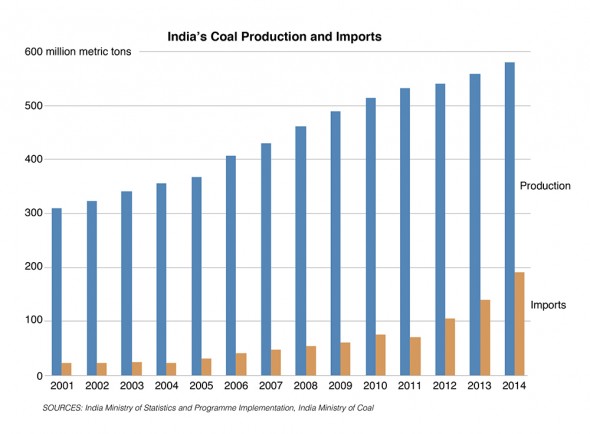

Graphics: India GDP – Growth Rate Slowing, India’s Power Production, and India’s Coal Production and Imports. Graphics by Erin Aigner and Circle of Blue Click images to enlarge.

|

||

It also is a landscape that defines a developing nation’s determination, even recklessness, to pursue an ambitious strategy of energy production and western-style economic growth almost at any cost, and without much regard for the costly side-effects.

The strategy isn’t working, though. The newest Central Government data on India’s economic performance shows that growth is slowing. Moreover, according to Central Government and independent statistics, at the current pace of growth in its energy production sector, India will not meet its energy goals until the end of the 21st century, if ever.

“You wonder: What’s the point?” said Patricia Mukhim, editor of the Shillong Times, whose daily English language newspaper closely covers the Meghalaya coalfields. “What purpose is being served by mining in this way? We will be left with nothing but a mess when it’s finished.”

You wonder: What’s the point?” said Patricia Mukhim, editor of the Shillong Times, whose daily English language newspaper closely covers the Meghalaya coalfields. “What purpose is being served by mining in this way? We will be left with nothing but a mess when it’s finished.” Photo © Dhruv Malhota/Contact Press Images for Circle of Blue

“What is happening here is a story that applies to all of India,” added Tony Marak, the principal chief conservator for the Meghalaya Department of Forests and Environment, a state land manager and regulatory agency. “We have problems with energy. We have problems with the economy. We have problems with coal mining and environment. We have problems with the government. We have been directed by the leaders of this state government not to look at any of this. They see it as a matter of survival. They tell us, ‘Don’t touch this.’”

Treacherous Mines

The Meghalaya box mine is a fiercesome sight. At the surface, it appears as a nearly perfect square of dark, empty air measuring 10 by 10 meters (32 feet). The sides of the mine, cut from limestone and sandstone, typically plunge 60 to 70 meters (197 to 230 feet) straight down to the coal seams at the black bottom.

There are two ways for Meghalaya’s miners to reach coal seams at the bottom of the shafts. Both are treacherous. The hardest path down is to descend, step by step, on the makeshift ladders constructed from tree branches that drop at steep angles along the mine’s four walls. Each section forms a switchback that drops down to join the next at the mine’s square corners. During the summer monsoon the ladders get slick with rain and mud. Falls are common.

The other way to the bottom of a box mine is to hitch a ride on the mine’s diesel winch. There’s enough room to stand on the empty bucket used to haul coal to the surface and grip the steel cable.

Maintenance and safety are not high priorities in Meghalaya’s coalfields. On Dec. 7, 2013, five miners died when the cable attached to the coal bucket they were riding down to the bottom of a box mine in the Jaintia Hills snapped.

Because the men and boys working in Meghalaya’s box mines are undocumented immigrants there is no formal record of workplace deaths and injuries. The Indian media, supported by estimates from human rights organizations, reported earlier this year that 100 miners have died in coal mining accidents in Meghalaya since 2012. Dozens more were killed in fights over women and gambling, holdups, and in attacks over bribes and take home pay.

“States like Meghalaya have allowed this activity to carry on unregulated on the plea that coal mining ‘is a cottage industry,’” writes Mukhim in her newspaper. “If the millions of tons of coal that is mined in Meghalaya is termed a cottage industry then one wonders what a full-fledged extractive industry would be. The number of coal trucks that carry the black ore from the mines of the Jaintia Hills, West Khasi Hills and Garo Hills on a daily basis should inform us that coal mining is hardly a cottage industry. It is a human activity that threatens to upset the ecological equilibrium of the state and, by association, the entire region. In Meghalaya we have a situation that is spiraling out of control.”

The 2012 Disaster

Arguably no mining accident more clearly confirms this undisputed history of lawlessness, or makes it easier to explain the indifferent official response, than the 2012 deaths of 15 miners who drowned in a box mine in the Garo Hills, the worst mine disaster in Northeast India in a decade.

After dawn on July 6, 2012, the foreman ordered 30 men to the bottom of the mine. Working in two-man teams, the miners crawled to the coal seams that lay at the end of long tunnels just three feet tall. Wielding steel axes and straight bars, they lay on their sides, the raw and damp dark lit by the glow from small flashlights taped to their heads. The sound of their work, the steady pounding of steel on rock, could be heard at the surface.

At some point the axes and bars of one of the teams broke through the rock, cracking open a hole. On the other side was a tunnel from an abandoned box mine that had filled like a giant bathtub with tens of thousands of liters of monsoon rainwater seeking a drain. A torrent burst through the hole, overwhelming two miners.

Fifteen miners heard it coming and raced up the slippery ladders made from tree trunks and branches to safety. A total of 15 miners drowned. It was the worst mine disaster in Meghalaya since 2002, when 40 men drowned in a similar accident. Word of the 2012 disaster didn’t reach authorities for days. Rescue operations were late in getting started and useless when they finally formed.

The incident attracted the attention of the National Green Tribunal, an appellate level court formed in 2010 to decide environmental cases. The accident also stirred the Meghalaya government to approve a new mining policy in November 2012, one the authors claimed would limit workplace safety and environmental risks.

The National Green Tribunal has expressed biting skepticism that state authorities mean what they said in the policy. Tribunal jurists openly mocked state government leaders who said in a hearing that nobody died in the July 2012 accident because none of the bodies were recovered. All may have escaped, said the state officials. “You come out with the truth or we will dig it out,” replied a clearly unimpressed justice, Swatanter Kumar.

Justice Kumar meant what he said. On Jan. 24, 2014, two judges of the National Green Tribunal convened a formal hearing in Shillong that was meant to put pressure on local authorities, and provide legal cover to Central Government and state regulators to reduce the safety and environmental risks of Meghalaya’s coal industry.

“The fate of human beings cannot be that of cattle and neither the state nor NDRF (National Disaster Response Force) could wash their hands of it,” said National Green Tribunal jurists M.S. Nambiar and Ranjan Chatterjee in a statement. “We are shocked to note that it is suspected that 15 human beings were inside the mine at the time of the mishap and suspected to be dead. There was no serious action to find out whether there was any labor inside the mine.”

On April 4, 2014, the National Green Tribunal leveled a startling frank assessment of the Meghalaya government, accusing them of indifference to safety and pollution in the state’s coalfields. The Tribunal said it was apparent the state’s two-year-old mining policy was being ignored, that pollution was rampant, and that miners continue to be killed.

The court cited the December 2013 accident in which the five miners were crushed to death, and issued several orders. It directed K .S. Kropha, the secretary of the state Department of Mining and Geology, to file a personal affidavit and comprehensive report “giving complete picture on record to the environment protection and anti-pollution devices, and the measures for protecting and control of pollution that are being taken.” The judges ordered Kropha to “state as to how many incidents of labor trapped or death have occurred in the state.”

The Lukha River, which drains the Jaintia Hills coalfields and then runs south into Bangladesh, supported an abundant fishery. One day in January 2007 the river turned sports drink blue. The discolored water killed thousands of fish. Their bodies formed a mat of white bellies pointed to the sun. Photo © Dhruv Malhota/Contact Press Images for Circle of Blue

Since 1999, seven big cement plant plants have been constructed in the Jaintia Hills. They receive limestone from local mines, are powered by captive coal-fired electrical plants, and produce almost 18,000 tons of cement daily. Landowners along the Lukha River are convinced that drainage from limestone mines is a factor in why the river turns blue. Photo © Dhruv Malhota/Contact Press Images for Circle of Blue

The court also directed the Central Government’s Pollution Control Board, one of India’s principal environmental regulators, to work with the Meghalaya Pollution Control Board to inspect the coal mines “and submit a comprehensive report with regard to carrying on mining activity in various places of state of Meghalaya particularly in relation to the pollution and danger to human life.”

Lastly, on April 17, 2014, the Tribunal issued an order to shut down mining in the Jaintia Hills, and in the two other smaller mining regions, calling it a grave threat to the environment and to workers. “We are of the considered view that such illegal and unscientific method can never be allowed in the interest of maintaining ecological balance of the country and safety of the employees,” said the justices. “It is also brought to the notice of this tribunal that by such illegal mining of coal neither the government nor the people of the country are benefited. It is only the coal mafias who are getting benefit by following this sort of illegal activities.”

The Tribunal set a hearing for May 19, during which Meghalaya state authorities said they would appeal the order because of its effects on worker wages and the state economy. “Mining and geology department is preparing necessary documents to appeal before the NGT,” said Prestone Tynsong, Meghalaya’s Forest and Environment Minister. “The ban would affect livelihood of many people. As far as child labor is concerned strict instructions have been issued to coal miners.”

In the meantime mining continues without interruption, and could stay that way indefinitely. By law, the Tribunal order to shut down mining must be implemented by the Meghalaya state government. “The state has a vested interest in allowing the continuance of rat hole mining,” said Patricia Mukhim, the Shillong Times editor, in an email message to Circle of Blue. “Unless there is a centrally appointed oversight committee to oversee the implementation of the ban it will be difficult to see the end of rat hole mining in Jaintia Hills.”

Two miners drag a cart of coal out of a rathole mine south of Shillong. The coal face is at the end of a tunnel over one kilometer long. It takes miners an hour to trudge to the coal face, an hour to mine and fill the cart, and an hour to pull the cart with $2 worth of coal back to the mine entrance. Photo © Dhruv Malhota/Contact Press Images for Circle of Blue

Small Player, Huge Affects

Were it not for the barbarous conditions, Meghalaya would hardly rank as an important part of India’s energy story. The state Department of Mining and Geology estimates that the state’s coal reserves amount to 600 million tons, a speck compared to the 294 billion tons of coal that India says are in its national reserves.

Meghalaya’s annual coal production now is around 6 million tons annually, or just over 1 percent of the 558 million metric tons that India mined in 2013, according to the national Ministry of Coal.

But because of the human hazards, and the enormous toll on the state’s water and land, Meghalaya’s unregulated mines and hazardous mining practices serve as a warning beacon. The feudal working conditions, the thousands of open and unreclaimed pits, and the toxic torrent of pollution that coal mining has unleashed on the state’s land and water illustrate two issues: The lengths to which India will go to increase its gross domestic product; and the indifference India displays to workers, the environment, and the rule of law.

These trends are in vivid view along the banks of the Lukha River, in southeast Meghalaya, which, like the empty buildings of Detroit or the radioactive fields around the Chernobyl nuclear station in the Ukraine, is a telling and tragic symbol of how the reckless pursuit of growth and wealth spirals out of control, yielding long-term decay and national neglect.

The Blue River

Until 2007 the Lukha River, which drains the Jaintia Hills coalfields and then runs south into Bangladesh, supported an abundant fishery. Villagers in the hills farmed small plots in forests so dense they were habitat for leopards and cobras. And they fished.

One day in January the river turned blue. Not a sky blue. It was an uncommon, bright, sports drink blue. The discolored water killed thousands of fish. Their bodies formed a mat of white bellies pointed to the sun.

The Meghalaya Pollution Control Board investigated and concluded the blue was formed by a tofu-like sulfate substance that coated the river bottom and reflected light from the sky. Samples showed the water was acidic, measuring as low as 3.0 on the pH scale, which accounted for the fish kill. The ideal pH for most organisms is 6.5 to 8.2.

The Pollution Control Board, though, is not sure what causes the acidity and the color change. What it knows, according to Arshister Lyngdoh, a 34-year-old zoologist and laboratory assistant, is that the color change has become an annual event. It arises in the fall and vanishes in the summer, with the advent of the monsoon.

The heavy summer rainfall provides a dilution factor that reduces the presence of the sulfate. When the monsoon stops in the late summer/early fall, the water chemistry changes, the sulfate forms anew, the acidity kills fish, and the river turns blue.

Initially, the Pollution Control Board blamed drainage from the high-sulfur coal mines of the Jaintia Hills. Groundwater streams through the mines. During the monsoon season water also is pumped out of the mines, and drains into streams and tributaries that eventually find their way to the Lukha River.

Local landowners have their own theories.

Since 1999, when the area’s first cement plant was built, six more cement plants have been constructed in the Jaintia Hills, according to state records. They receive limestone from local mines, are powered by captive coal-fired electrical plants, and produce almost 18,000 tons of cement daily, according to the state Pollution Control Board.

Downstream landowners are convinced that drainage from limestone mines, the cement plants, and the runoff from coal stored at the captive plants somehow influences the chemistry of the region’s rivers, killing fish and turning the Lukha blue. It’s a local theory that the state Pollution Control Board neither embraces nor dismisses.

Very clearly, the condition of the Lukha River, and the tide of danger that rushes the coalfields it drains, define India’s newest challenge. The world’s fourth largest economy is scrambling to match the economies of the United States, China, and Western Europe. But India’s operating system, riven with inefficiencies and corruption, slowed by a stifling bureaucracy, and tolerant of excessive pollution and enormous human risks, does not appear capable of delivering on that goal.

The coalfields of Meghalaya are a microcosm of India’s circumstance. The world’s second largest country is in dire need of a new definition of the good life. Though Meghalaya is a staging ground for pursuing India’s economic, energy, and social goals, what it’s producing is an energy paradox and environmental pandemonium.

On a recent trip to the Lukha River, Arshister Lyngdoh stood barefoot in the shallow water along the bank, his pants rolled up to his knees. He dipped a pipette into the water and applied a drop to a slim, paper pH test strip. The strip turned a shade of yellow/green that indicated the water measured a pH of 4.5, sufficiently acidic to kill fish.

“We have good knowledge of what is happening to the river,” Lyngdoh said, as if summarizing Meghalaya’s situation. “We don’t know why it is happening. We don’t know what we can do.”

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

This is real hard hitting facts and recently I have just received information that only 4 of the cement plants in Jaintia Hills got Environmental Clearance and strange that they did not reply when asked how many industries near their plant….In a radius of 5 km about 8 cement factories. the rich make their money and shift but the poor have to face the hardships and the water bodies polluted.Thanks for taking up the cause of our people…